![]() Brickmaking at Martham

Brickmaking at Martham

This topic is long so I have divided it into two main sections. The first – SECTION A – is a summary that you can read in about ten minutes and the second – SECTION B – is the full article in detail. You can jump to any section by clicking on it.

SECTION A – Ten Minute Summary

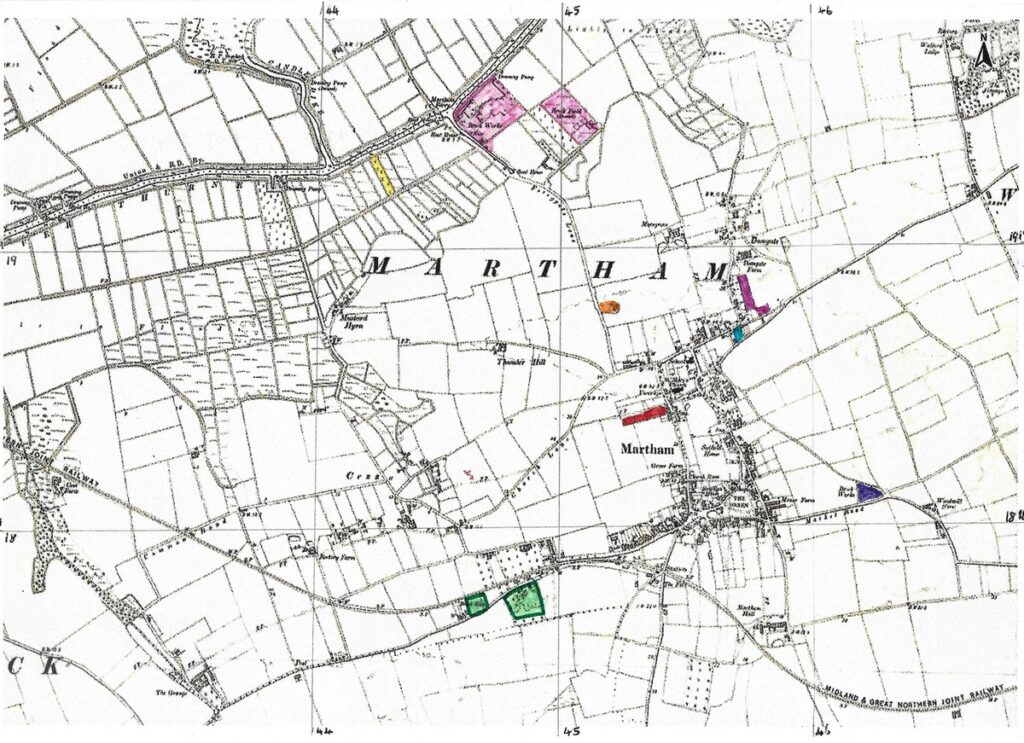

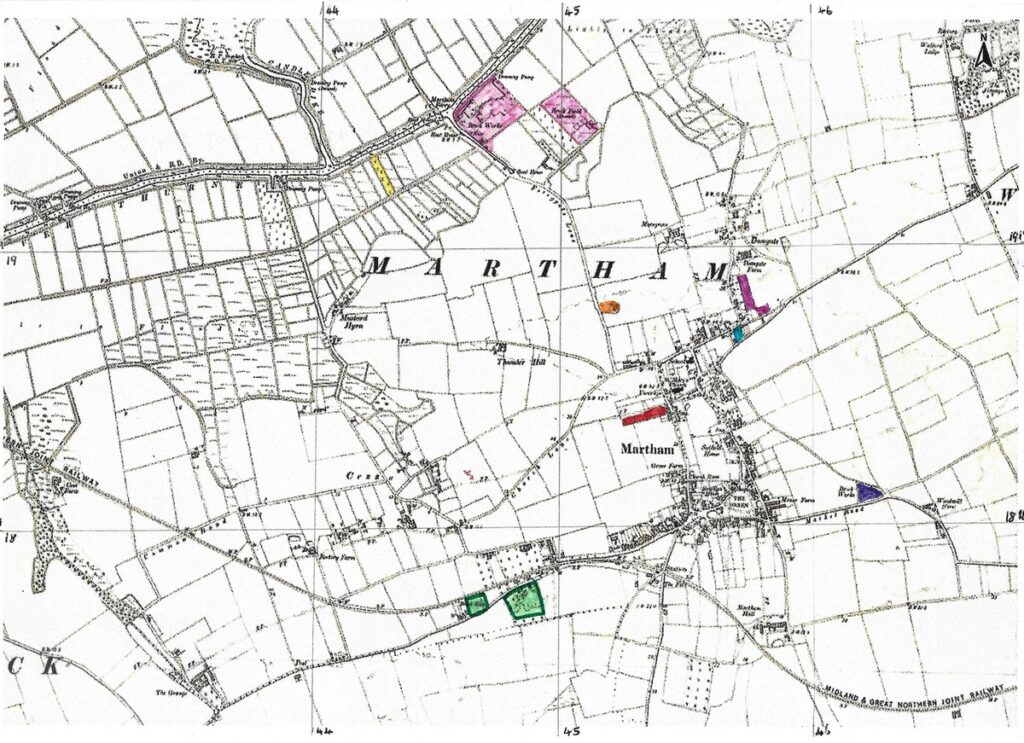

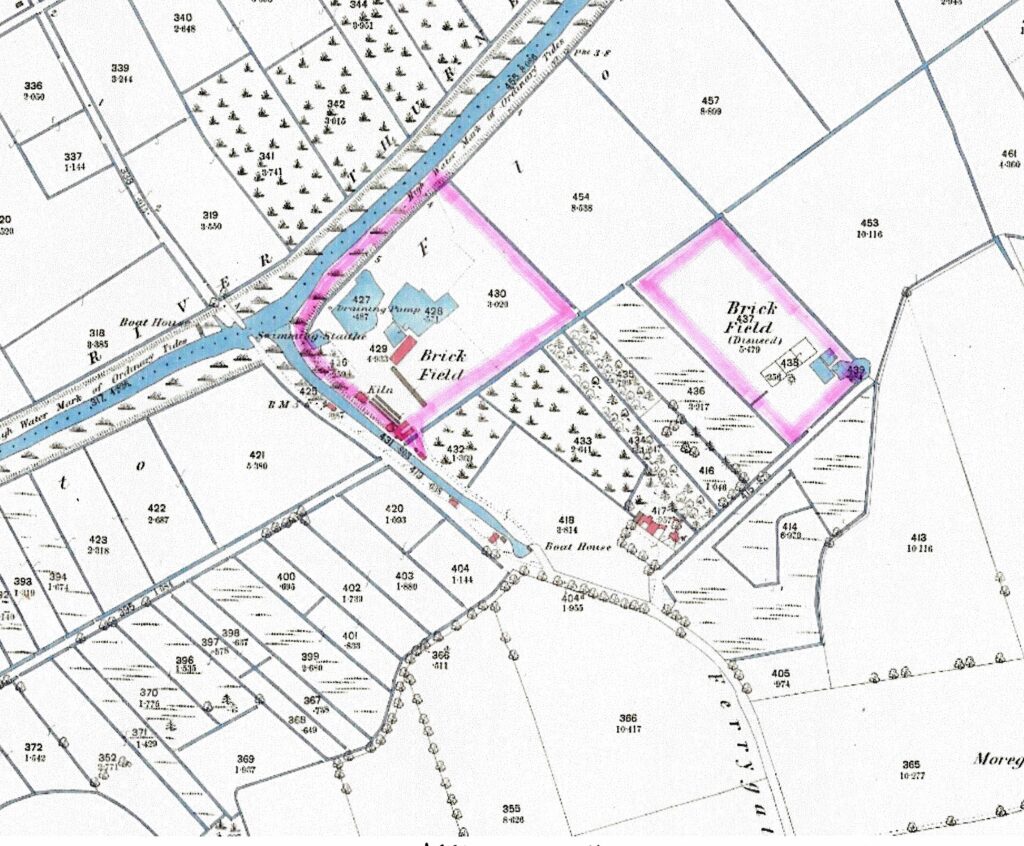

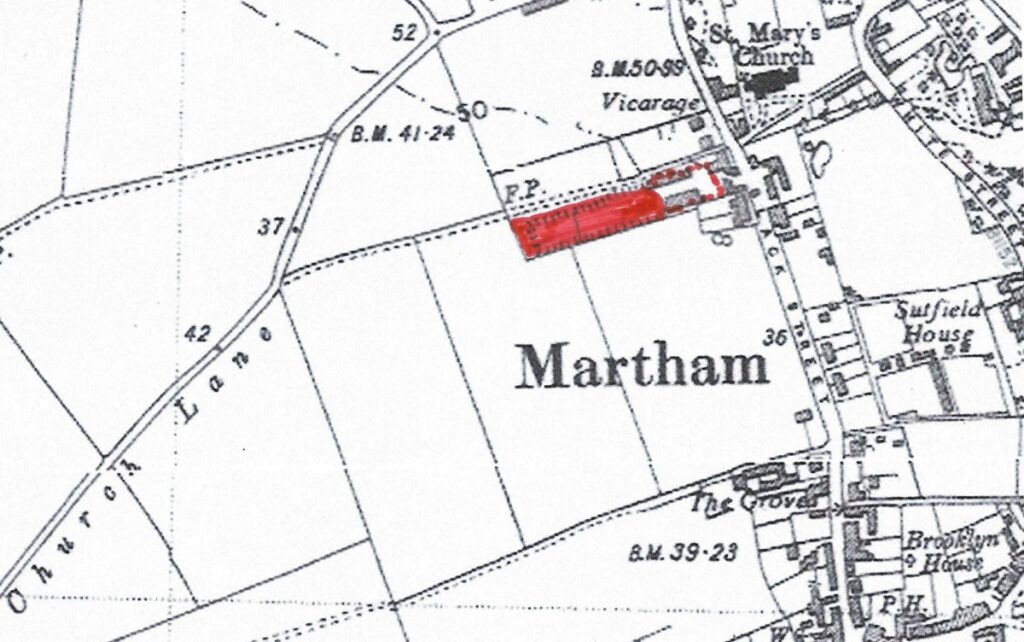

There were at least seven or eight brickyards in Martham, (one is a little uncertain). They are highlighted in different colours on the map below.

History

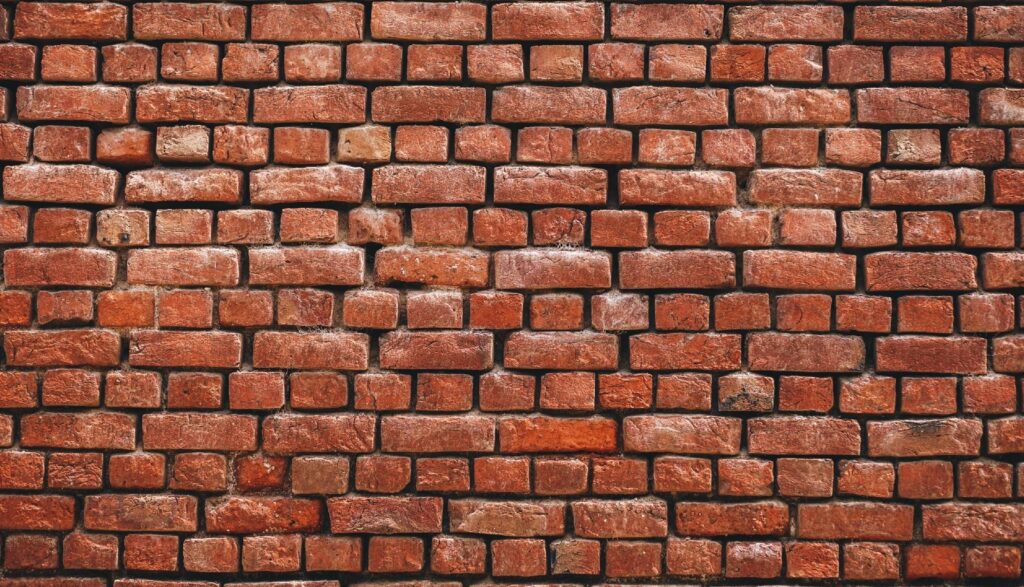

Brickmaking flourished in Martham, particularly in the 19th century because of the availability of suitable clay and brick earths(3) which were formed millions of years ago in post glacial conditions. Brick earth could be mixed with estuarine clay that when fired made stronger bricks(3).

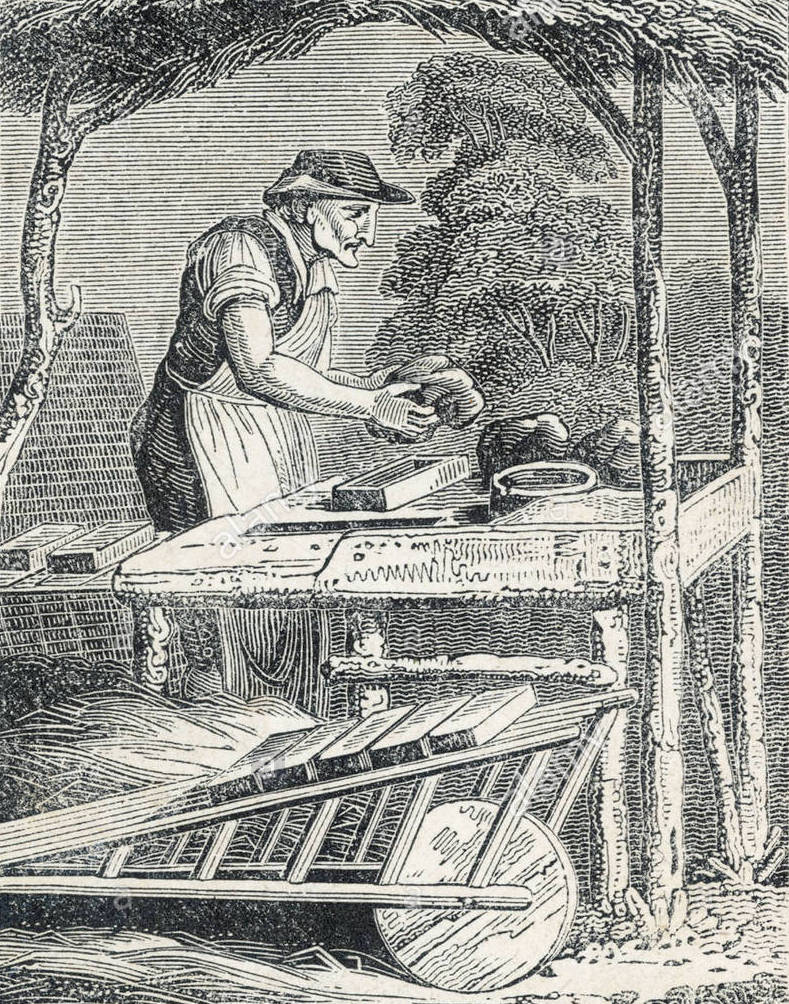

Brick making was brought to Britain by the Romans but fell into decline after their departure. The earliest known post-Roman bricks date from the early-thirteenth century, when Flemish bricks were imported. Flemish and Dutch people then settled in England bringing their skills with them. Many of these Flemish migrants settled in the East of England; brickmaking flourished and they influenced brick making locally making use of the good supply of suitable clay and brick earth. During this period brickmakers travelled to construction sites to make bricks from the local clay rather than get them from larger production sites.

Mechanisation came to the brickmaking industry in the 1820s and with improved transport infrastructure permanent brickyards became established which could produce many thousands of bricks per day with a smaller workforce than was needed to produce them by the old hand craft system. In 1850 Great Britain abolished its brick tax that had been established in 1784. In and around Martham the industry made good use of the Broadland waterways and wherries for transporting bricks before the arrival of the local railway in 1878. The combination of mechanisation and removal of the brick tax gave rise to a large increase in production. The small country yards, unable to invest in machinery, were either bought out or driven to closure.

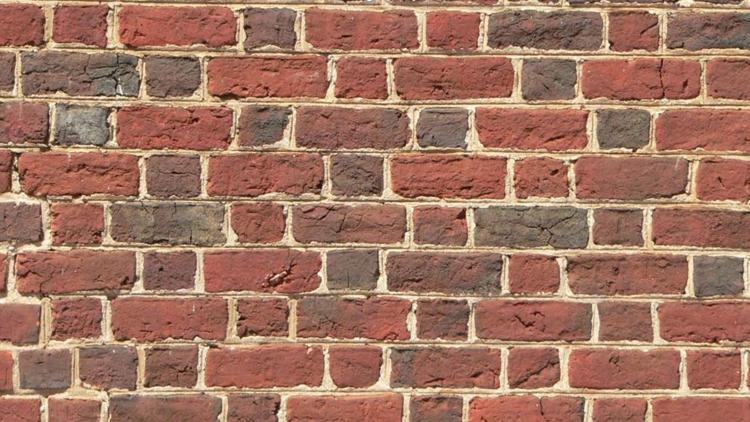

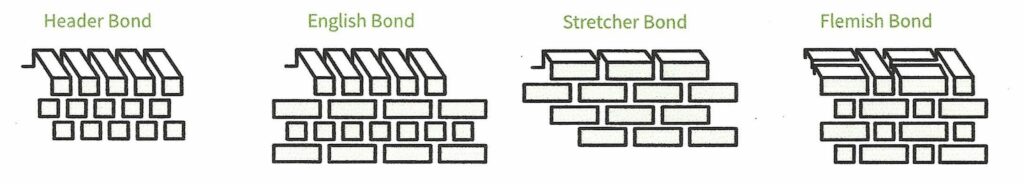

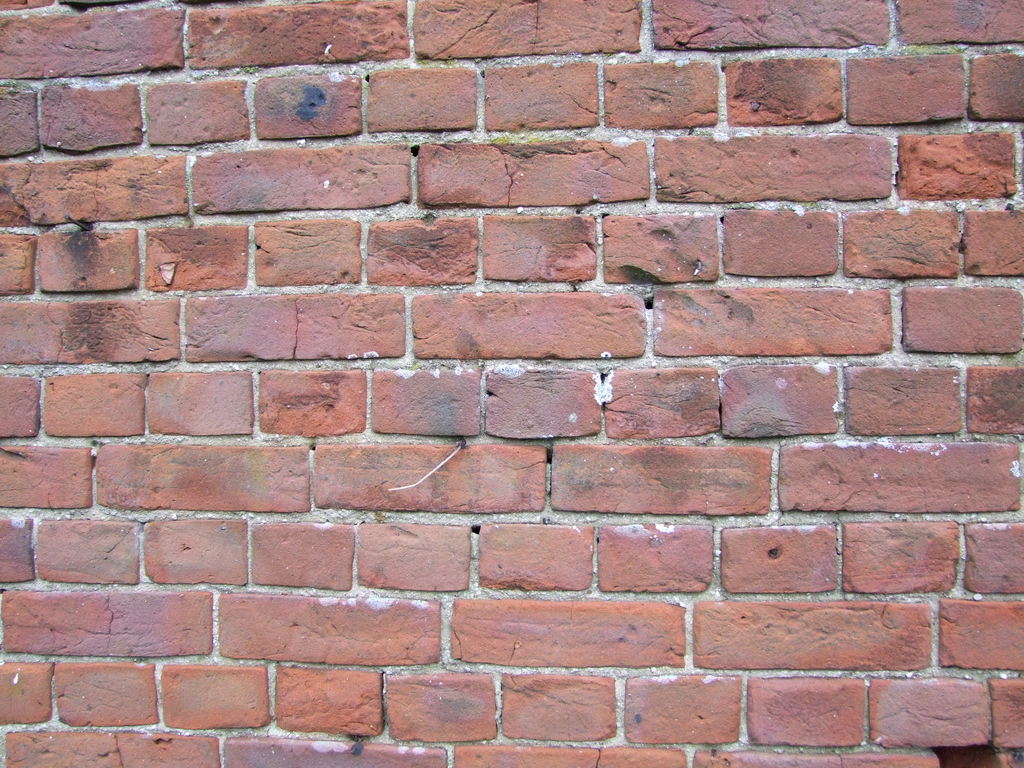

Some buildings can be roughly dated based on the brickwork pattern (bond) used . English bond dates roughly from the mid 17th century to the 18th century by which time the more decorative Flemish bond became more popular.

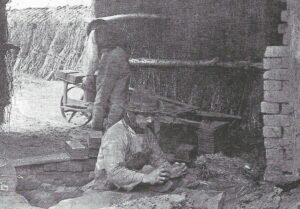

Making Bricks

Bricks are generally made from tempered clay or brick earth dug from the ground and sometimes mixed with sand. It is picked clear of stones and other unwanted matter and then mixed to the right consistency for brickmaking. The clay is then thrown into wooden moulds to form the shape of the brick. When moulding a brick, it is vital that no air is trapped inside the clay. Excess clay is removed by running over the mould with a wire. The bricks would then be left to dry for at least 48 hours in a shed or south facing field.

When the bricks were dry enough, they were stacked to form a kiln in order to bake them. Flues were set into the stack and timber or coal fires prepared. The fires were lit and the bricks were “burnt” in stacks containing between 800 and 1,000 pieces. Firing usually took two to three days reaching a temperature of around 1,040 degrees centigrade. They were then allowed to cool naturally and the temporary kiln dismantled and the bricks sorted and stacked ready for use. The whole process could take a long while depending on the weather and it tended to be seasonal to avoid frosts.

The colour of a brick is determined by the chemical composition of the clay, the fuel used to fire them and the levels of oxygen available during the firing process. Martham bricks were traditionally burnt red and called Norfolk or Martham reds which were good quality and could withstand frosts.

Martham Brickworks

1. Bracey’s – Hemsby Road Brickworks.

Grid Reference: TG 4626 1808.

This site belonged to William James Bracey (1847-1922) and is shown in purple on the map above. The site provided good quality brick earth.

2. Bracey’s – Windpump Brickfield, near the Thurne Riverside.

Grid Reference: TG 4356 1897.

This is the site that has been questioned by some experts. It is claimed to have been next to and south of the windpump that still exists today. The site is shown in yellow on the map above.

3. Brickfield Farm Brickworks, Staithe Road.

Grid Reference: TG 4570 1888.

Shown in light blue on the map above, this site was at what is now 25 Somerton Road. The farm and brickfield existed at the time of the 1812 Inclosure Award when they were owned by George Wilson (1748-1834) and they remained in the ownership of the same family until 1851. The date that brick production came to an end is unknown but it could have been at about this time as no records exist of subsequent owners of Brickfield Farm being associated with brickmaking.

4. Chapman’s Pit Brickworks (or Bottomless Pit), Ferrygate Lane.

Grid Reference: TG 4508 1944.

Shown in orange on the map above, this site once consisted of a mound 4ft high contained by two concentric 19th century brick walls. The outer one was 20ft in diameter whilst the inner one was 8ft. There was one flue and three rectangles to the north. The site came into use between 1812 and 1842. The date it ceased production is unknown.

5. Damgate Farm, Damgate Lane.

Grid Reference: TG 457 191.

This site is shown in magenta on the map above. The 1884 OS map refers to two brick yards and a nearby sand pit . Kelly’s Business Directory entries indicate that the site was in use towards the end of the 19th century but when it ceased production is unknown.

6. Ferrygate Staithe Brickworks (also known as Martham Pits).

Grid Reference: TG 447 195.

This site is the best known in Martham mainly because its former clay pits have flooded and now provide some excellent fishing. Shown in pink on the map above, parts of the site were easily accessible to Ferrygate Lane Staithe for brick distribution. It was once a large site of about 10 acres with kilns for both brick and tile making. It also had a small railway and temporary skeleton windpump. The eastern section was disused by 1884 probably because the clay there had been exhausted. The brick field was owned by Robert Moore who was very entrepreneurial and it was sold as a going concern shortly after his death in 1885. William Bracey bought the site at auction after the death of Robert but its eventual closure date is unknown.

7. Goose’s Brickworks, Repps Road. (Also known as Gowen’s Brickfield).

Grid Reference: TG 449 176 on the south side of Repps Road and TG 447 175 on the north side.

Shown in green on the map above, this site was on the south side of Repps Road roughly where Bosgate Rise is today and opposite on the north side of the road. There was a kiln on the south side of the site. John Goose (1767-1847) owned the land there in 1812 and 1842. There was no mention of it being a brickyard in 1812 but by 1842 part of the site was in use for making bricks. By 1891 brickmaking was still in production and the business was owned by James Gowen (1827-1899). The 1906 OS map marks ‘Old Brick Kiln’ on the north side of the site with pits. The revision of the 1938 OS map shows no sign of the brickworks at either site.

8. Linford’s Brickyard, Black Street.

Grid Reference: TG 4537 1834.

Shown in red on the map above, this site is better known to many locals as the former Kirby’s Yard that is now Oak Tree Close. In 1822 Moses Linford owned the site and made good use of the land that had a 15ft thick seam of brick earth of the same quality as that at Bracey’s Hemsby Road site. Moses’ son James had taken over production by 1842. There was a brick kiln in use at the site in 1852. The site was purchased by James Edwin Kirby in 1911. He had started out as a brick and salvage merchant and when the brick earth became exhausted it was his descendants that turned the remaining pit into Kirby’s haulage and farming contractors yard.

Martham Properties Built of Norfolk Red Bricks

In the past many buildings could be found in the village built with ‘Norfolk Reds’ made in Martham. Not many remain but those that do provide the best evidence of the industry and some show high quality workmanship. The following are just a few examples:

- 60 – 70 White Street.

These are some of the oldest surviving cottages in the village dating to the 16th century. They were originally timber framed homes and were brick faced in the 17th century. The south end gable to No60 is in the traditional English brick bond which alternates between stretcher and header courses. The front of No60 has a mixture of English and Flemish bond but was rendered until recent years and the original pattern may not have been particularly stylised if it was going to be covered in render.

- Baptist Chapel, The Green.

The existing chapel in the north west corner of The Green was built of red bricks donated by Robert Moore (1825-1885) the owner of the Ferrygate Lane brick ground. The chapel was opened in 1880.

- Barn Rear of 23 Black Street. This much overlooked small barn has been subject to many repairs over the years but original Norfolk red brick parts have been faithfully copied in English bond.

- Bell Yard Cottages, White Street.

If you want to see a grand mix of styles, including flint work, look at the rear of these cottages on the Church side where you can see not only early 18th century English and Flemish bond patterns but a mixture of both.

- Brickfield Farm Barn, Staithe Road.

This ancient red brick barn has a mixture of brick patterns, predominantly English bond and some Flemish bond.

- Hemsby Road Barn. (Mill Barn)

There were plans at one time for this barn to be uprooted and moved a few hundred yards west but it did not happen. One wonders what they would have done with a barn that has gable ends in the old English bond but (probably repaired) Flemish bond on the east side facing the road.

- Martham House, Threshing Barn, Pratts Loke.

This early built threshing barn originally belonged to Martham House and still stands at the time of writing (2023) in Pratts Loke, off Somerton Road. A closer look at the barn indicates that it was probably built in around 1700 of bricks made in Martham as can be seen from the English bond bricklaying style.

- Moregrove Barns.

Another early example of red brick barns is the pair at Moregrove. They stand on the north side of the site and are Grade II Listed (1987) probably built in the very early 19th century. High up inside the west gable end the name Benjamin Rising (1775-1835) is inscribed giving a good indication of the age of the buildings. The north east side of the barns has distinctive Flemish bond brickwork.

- Norwich House.

This elegant early 19th century house stands on the north side of The Green. In its time it has also been a shop. Built in Flemish bond.

- Staithe Road Cottages (9 & 11), near Clarke’s Farm.

Not much is known about these cottages built in the mid 19th century as labourers cottages. In 1842 they were owned by Robert Beverley. They have clear Flemish bond brickwork.

- The Lodge Gatehouse, White Street.

This former gatehouse to Martham House shows fine Flemish bond craftsmanship and window arches. Built c1870.

- Westgrove, 9 Rollesby Road.

Built of Norfolk red bricks Westgrove is a substantial early Edwardian house set back from the east side of Rollesby Road. It was built in 1915 for Oliver Starling by local master builder Henry Futter.

People Associated with The Trade

At the very end of the longer section below is a table of people that worked in or were associated with the Martham brickmaking trade. It is not a comprehensive list of everyone involved as it was drawn up based on various records representing snapshots in time. We have seen that brickmaking was seasonal and this is illustrated by the large number of people that worked in the trade also having other jobs.

The list also shows that a large number of men in the trade did not come from Martham. People followed the availability of work or better pay and this is particularly so in the second half of the 19th century when building was at its peak in the village.

For full details about the people that worker in the industry see Part D below.

SECTION B – the full report in detail.

There were at least seven or eight known brickyards in Martham (one is uncertain) and they are highlighted on the main map below. They are coloured for identification and more details are given in Part B below.

This section is divided into four parts. You can jump to any part by clicking on it.

Part A – General History and Methodology of Making Bricks.

Part B – The Brickworks of Martham.

Part C – Martham Properties Built of Norfolk Red Bricks.

Part D – Some Martham people associated with the trade.

Part A. General History and Methodology of Making Bricks.

Brick making was brought to Britain by the Romans but fell into decline after their departure and it was not unusual for bricks to be reused from rundown buildings or excavations. The earliest known post-Roman bricks date from the early-thirteenth century, when Flemish bricks were imported. Many Flemish and Dutch people then settled in England bringing their skills with them, these were mainly in textiles but they were also highly regarded for their brick making and laying skills. Consequently, English brick production increased and the numbers of imported bricks declined. Many of these Flemish migrants settled in the east of England and they influenced brick making locally making use of the good supply of suitable clay and brick earth. The distinctive Flemish brick pattern they brought with them can still be seen in some buildings in Martham to this day, for examples see part C below.

During this period brickmakers travelled to construction sites to make bricks from the local clay rather than get them from larger production sites. The craft was regulated, at first by church guilds and then later by specific guilds of tilers and brickmakers. The oldest of these was the Worshipful Company of Tylers and Bricklayers, founded in 1416 and Chartered by Queen Elizabeth I in 1568.

Mechanisation came to the brickmaking industry in the 1820s and with improved transport infrastructure – first canals and then railways – permanent brickyards became established which could produce many thousands of bricks per day with a smaller workforce than was needed to produce them by the old hand craft system. In and around Martham the industry made good use of the Broadland waterways and wherries for transporting bricks before the arrival of the local railway in 1878. In 1850 Great Britain abolished its brick tax, a tax per brick used in construction that had been established in 1784 to pay for the American Revolutionary War. The combination of mechanisation and removal of the brick tax gave rise to a large increase in production. The small country yards, unable to invest in machinery, were either bought out or driven to closure and itinerant craft brickmakers could not compete. These factors must have affected brick production in Martham in much the same way as other parts of the country but there may have been a delay factor due to its remoteness.

Bricks are generally made from tempered clay or brick earth dug from the ground and sometimes mixed with sand. It is tested for suitability and picked clear of stones or other unwanted matter and then mixed to the right consistency for brickmaking. Historically, the clay would be tempered by the weather and water under foot in open pits for two to three days. The clay is then thrown into wooden moulds to form the shape of the brick. When moulding a brick, it is vital that no air is trapped inside the clay. Excess clay is removed by running over the mould with a wire. The mould would be coated with sand to act as a release agent for the clay. The clay would be compacted by hand or a piece of wood and any excess would be skimmed off level with the top of the mould. The brick would then be removed onto a thin board and taken to the drying shed or a flat, south-facing field and laid out to dry for two days and two nights, being turned during that time to assist initial drying, then turned again on edge and stacked in rows, one on top of the other, to dry for a period usually extending between one and three months depending on the weather and time of year.

When the bricks were deemed to be dry enough, they were fettled (trimmed of “flash”) and stacked to form a kiln in order to bake them. Flues were set into the stack and fuel was then prepared, usually timber or coal. The fires were lit and the bricks were “burnt” in stacks containing between 800 and 1,000 pieces. The firing usually took two to three days including nights of continuous firing and reached a temperature of around 1,040 degrees centigrade. They were then allowed to cool naturally and once cooled were dismantled and the bricks sorted and stacked ready for use. This process of using temporary stack kilns and traditional firing methods was called “clamp firing” from which clamp bricks were produced. It allowed for the production of durable and reliable bricks without the need for advanced kiln technology. We will come across the term clamp bricks again in part B.

The whole process of digging the clay, drying and firing could take a long while and if drying time depended on the weather rather than taking place in a drying shed it could take many months. The process tended to be seasonal. The year progressed as follows:- February to April the clay was dug. May to August the bricks were made and left to dry once frosts were less likely. September and October the firing time. During the winter brickmakers were often unemployed which shows why many of those listed in Part D had second jobs as well as brickmaking.

The colour of a brick is determined by the chemical composition of the clay, the fuel used to fire the bricks and the levels of oxygen available during the firing process. Iron oxide gives the brick a red colour, very high levels of iron oxide gives a blue colour, limestone and chalk added to iron gives a buff/yellow colour, magnesium dioxide gives a deep blue colour, and no iron or other oxides gives a white colour. Martham bricks were traditionally burnt red and called Norfolk or Martham reds which were good quality and could withstand frosts.

Although the sizes of bricks varied from area to area through the centuries, by the early-nineteenth century bricks were manufactured to a statute which required that they should be twice as long as they were broad, normally being 8 by 4 inches or 9 by 4.5 inches.

Part B. The Brickworks of Martham

Martham had several brickworks in the 19th century and before that bricks would probably have been made on common land alongside the River Thurne as well as on individual sites but the following were production brickworks.

1. Bracey’s – Hemsby Road Brickworks.

Grid Reference: TG 4626 1808.

Norfolk Historical Environmental Record (NHER) No 16665.(4)

This is the site of a brickworks that belonged to William James Bracey (1847-1922) and is shown in purple on the main map above and in the same colour pinpointed on the more detailed map No1 below. The site provided brick earths(3) which are eriglacial loess of wind-blown dust deposited under extremely cold, dry, peri- or postglacial conditions. The name arises from its early use in making house bricks without additional material being added and unlike clay the bricks can be hardened at lower temperatures. Later it was found that brick earth could be mixed with estuarine clay that when fired made stronger bricks(3). NHER(4) reports from 1980 say the footings of brick kilns survive on the site.

The site is shown on the 1880 hand drawn map No9 shown below.

It also existed in 1909 because it is included in the Inland Revenue Duties on Land list as being liable under the Finance Act (1909/10) along with the Ferrygate Staithe brickworks both of which were owned by W & W Bracey at that time.

2. Bracey’s – Windpump Brickfield, near the Thurne Riverside.

Grid Reference: TG 4356 1897.

Norfolk Historical Environmental Record (NHER) No 14964(4). The site is shown in yellow on the main map above and pinpointed in the same colour on map 2 below.

There are four former ponds visible as earthworks on aerial photographs which could be construed as being associated with brickmaking at the site but the NHER(4) says this is uncertain. Bracey’s Wind Pump is adjacent. It was built in 1908 by the Commissioners for Drainage and two of them were William James Bracey (1847-1922) and his son, also William (1870-1949). William senior had been a builder in his early career and was well placed to build the windpump. It seems obvious that any nearby clay resource would have been utilised for making the bricks to build the windpump but the NHER(4) reports cast some doubt on this. Other NHER(4) reports talk about both three and four ponds being there as well as changing its grid reference, so there may be some confusion with the nearby Ferrygate Staithe pits brickworks.

Archaeology Society’s files on brickmaking at Martham in the 19th century identify two yards owned by William Bracey: one at Hemsby Road (NHER 16665) and another to the west of Ferrygate Staithe (NHER 16663). This site is not mentioned in the Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society(7) notes on brickmaking, nor is it shown as a brickfield on any historic Ordnance Survey maps.

3. Brickfield Farm Brickworks, Staithe Road

Grid Reference: TG 4570 1888.

Norfolk Historical Environmental Record NHER(4) No 16667.

Shown in light blue on the main map at the top of this page this site is on the south side of what we now call Staithe Road directly across the road from Brickfield Farm. It was on the plot that is now occupied by 25 Somerton Road. In the days when the brickfield was in use Staithe Road was called Damgate Road. Records of the Norfolk Archaeological Unit say there was once a kiln here that was like the one at Chapman’s Pit brickworks but smaller. The brickfield gave its name to the farm and is inextricably linked to the history of it.

According to the 1812 Martham Inclosure Award there was a cottage standing in one rood of land on the site where Brickfield Farm stands today. It is shown, outlined in red, on map 3 on the right as is the brickfield which is shown in blue. The farm and brickfield were owned by George Wilson (1748-1834) but occupied by his son-in-law William Braddock (1777-1864) and his wife Elizabeth. George Wilson died in 1834 and it seems that William inherited George’s land through his wife.

William & Elizabeth had a son called Charles in 1811 who had taken over the brickmaking side of their interest by 1842 when he was the owner of the “brick ground” that was listed as plot No10 as shown on the Tithe map below. His father was listed in the Tithe Document of 1842 as the owner of the farm (on plot No15).

Charles also owned the adjoining plot No11 which may have been part of the works and the two plots measured one acre and one perch. No 10 was the brick ground. Both plots are shown outlined in red on the map above and are opposite Brickfield Farm. Like other brickfield owners Charles had other jobs and was also a brewer and a cooper. He was also listed as a brickmaker in three Martham business directories between 1846 and 1850. The date that brick production came to an end is unknown but the Braddock family association with Brickfield Farm came to an end when Charles died in 1851.

4. Chapman’s Pit Brickworks (or Bottomless Pit), Ferrygate Lane.

Grid Reference: TG 4508 1944.

Norfolk Historical Environmental Record NHER(4) No 16664.

Shown in orange on the main map at the top of this page and in the same colour pinpointed on the map above this site was part of the Moregrove Estate owned by the Chapman family since 1919. A report by the Norfolk Archaeological Unit dated June 1980 says that it once consisted of a mound 4ft high contained by two concentric 19th century brick walls. The outer one was 20ft in diameter whilst the inner one was 8ft. There was one flue and three rectangles to the north. It may also have been a tile works and had a tile kiln. There are no visible remains of these today.

It does not appear in the 1812 Martham Inclosure Award or its accompanying map. It is listed in the 1842 Tithe Award as plot No 426 measuring one rood and twenty perches and described as a “clay pit and pasture, ploughed”. This perhaps indicates that it first came into use as a clay pit between 1812 and 1842. As part of the small plot was ploughed pasture in 1842 clay extraction must have been minimal and any brickmaking came later. A copy of that portion of the Tithe map is shown below.

In 1842 the plot was owned by William Henry Garnham as part of the Moregrove Farm but he was only an investor in the estate as he was a wealthy silk draper living in London. The tenant farmer there was Silvanus Grove Hillersdon (1816-1891) who was born in London.

5. Damgate Farm, Damgate Lane.

Grid Reference: TG 457 190.

There is no Norfolk Historical Environmental Record for this site.

This site is shown in magenta on the main map at the top of this page and pinpointed in the same colour on the more detailed OS map of 1884 below. The map refers to two brick yards and nearby sand pits. The boundaries and access point(s) to this site are uncertain as very little exploration has been carried out. The hatched areas to the east (right) are speculative. Local lady Karen Brooks says (on Facebook 2023) that there was a kiln at Damgate Farm where her relative Eldred Edgar Brooks lived in 1901. Eldred was born in Martham in 1865. By 1891 he was a master bricklayer and is listed in the 1892 and 1896 copies of Kelly’s Directories as a bricklayer.

6. Ferrygate Staithe Brickworks (also known as Martham Pits)

Grid Reference: TG 447 195.

Norfolk Historical Environmental Record NHER(4) No 16663.

This site is the best known in Martham mainly because its former clay pits have flooded and now provide excellent fishing pits. Shown in pink on the main map at the top of this page and pinpointed on the more detailed map below parts of the site were easily accessible to the east of Ferrygate Lane Staithe.

It was once a large site of about 10 acres which not only had kilns but a small railway and its own temporary skeleton wind pump. Local man William Buck says (on Facebook 2023) that he can remember the narrow railway track which went from the nearby works to the riverbank where wherries were moored up and took bricks to destinations like Great Yarmouth and Norwich. This is also mentioned by Tom Williamson(3).

The above map indicates that the clay pits were used over time as the eastern section was disused by 1884 after the clay there had been exhausted. The map shows kilns next to the staithe which must have assisted easy loading onto wherries(3). Being next to the river the site must have been subject to flooding because a skeleton wind pump was in use at one time(3) which is shown in the photo on the left below. Just beyond the south eastern end of the staithe there was a house which was a ruin by the early 1960’s. It was occupied by William Samuel Starkings (b1867) who was a bricklayer’s labourer in 1881.

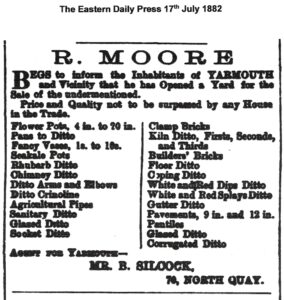

The brick field was owned by Robert Moore (1825-1885) who was very entrepreneurial. He was a coal, corn, seed, hop merchant and farmer as well as a brick merchant. His father, of the same name, was a grocer at the building that would much later become known as Clowes Stores on The Green. Robert Jnr. had taken over from his father at the store but diversified into a wider range of business interests. He was producing a wide range of clamp bricks and associated items which we know about because in 1882 he opened a yard at Great Yarmouth selling all manner of brick and tile related items that were probably made at his Martham Ferrygate brick field. Below is his advert listing the things he had for sale from which we get a good idea of what he was producing. His agent, Boardman Silcock, was his son-in-law, the husband of his daughter Mary Ann.

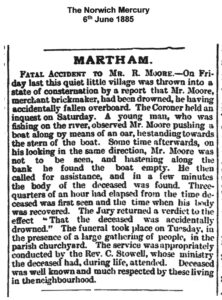

Tragedy struck on 29th May 1885 when Robert was drowned in the River Thurne next to his brickfield. The circumstances were reported in The Norwich Mercury on 6th June and the report is shown below.

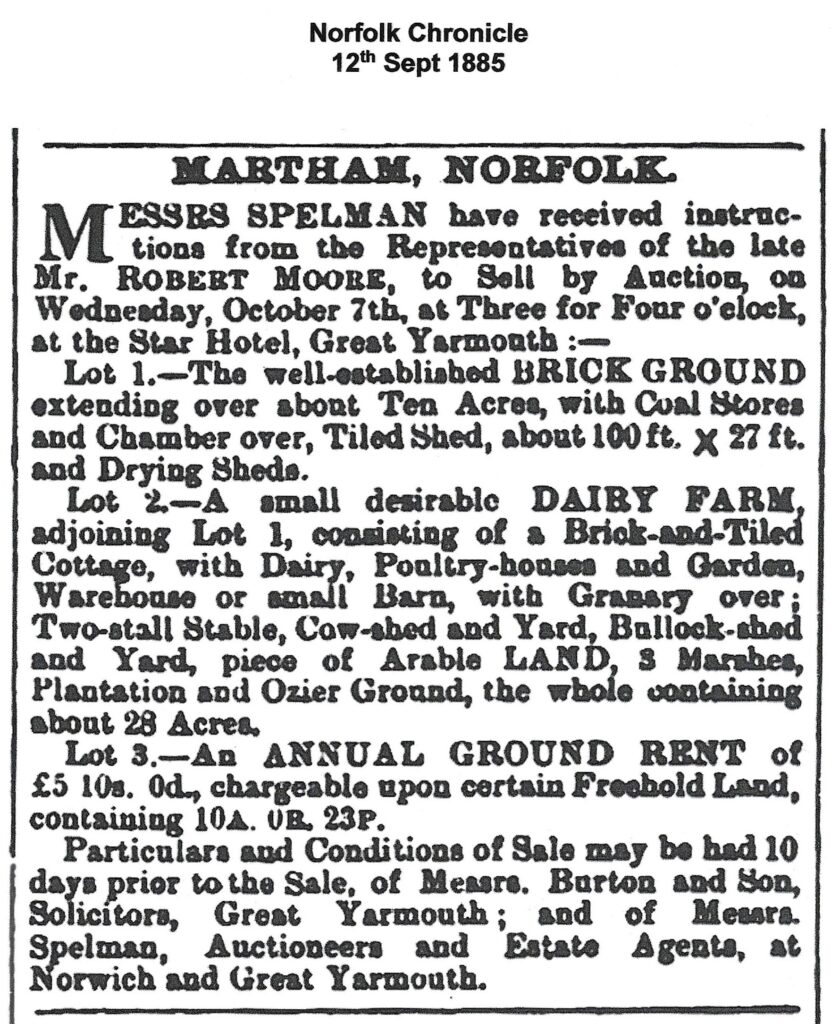

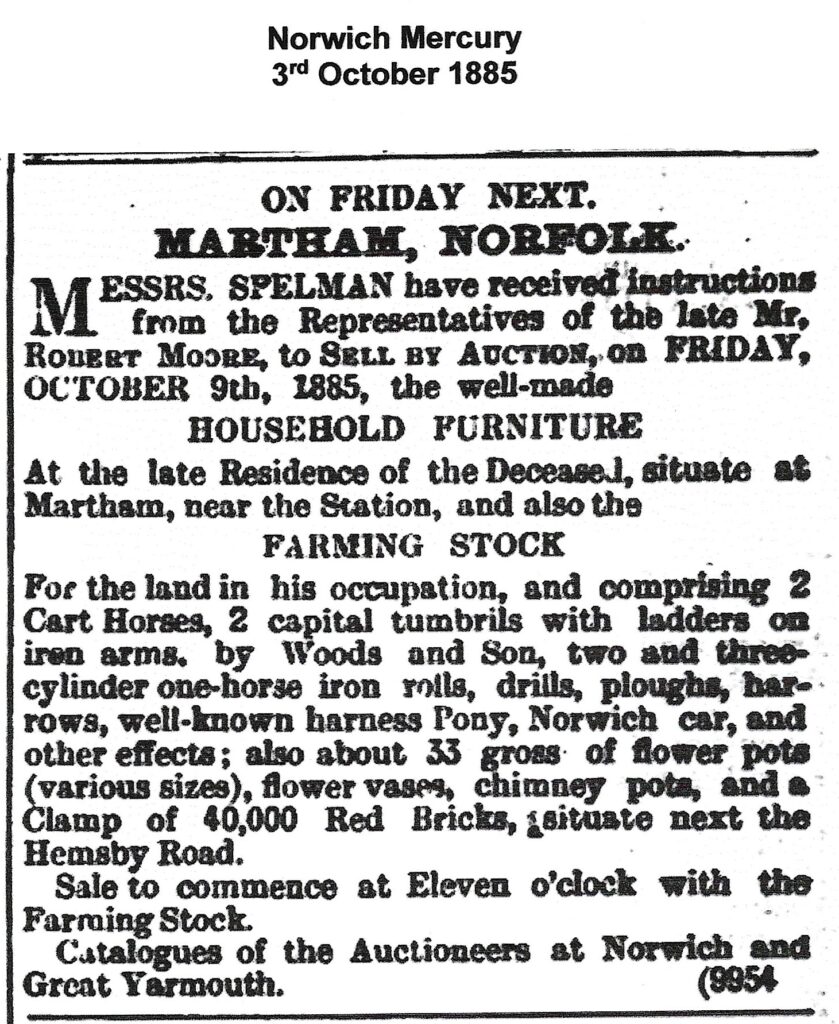

Following his death auction sales were held for the brick ground and his household goods and farming stock. These are shown below. The adverts give us more information about the brick ground saying it was about ten acres in size, had a coal store (for the kilns) and a very large tile shed of about 100ft x 27ft as well as a drying shed. We get an idea of the brick production from the advert dated 3rd October 1885 when 40,000 red clamp bricks were put up for auction.

The Yarmouth Mercury of 10th October 1885 reported that Robert’s brick ground and premises were sold for £400. A dairy he owned consisting of 28 acres, 2 roods & 22 perches sold for £610 but the report did not say who purchased the two lots. The buyer is believed to be William Bracey (1847-1922) who was a dairy farmer who already owned two other brick grounds – see above. Tom Williamson(3) says that William Bracey ran carts back and forth between his three sites taking brick earth from the Hemsby Road site to the others and estuarine clay from his Ferrygate Staithe site so the two could be mixed and fired at both sites which produced stronger bricks.

The site is shown on the 1880 hand drawn map No9 shown below.

It also existed in 1909 because it is included in the Inland Revenue Duties on Land list as being liable under the Finance Act (1909/10) along with the Hemsby Road brickworks that were both owned at that time by W & W Bracey.

7. Goose’s Brick Works, Repps Road. (Also known as Gowen’s Brickfield)

Grid Reference: TG 449 176 on the south side of Repps Road and TG 447 175 on the north side.

Norfolk Historical Environmental Record NHER(4) No 16668.

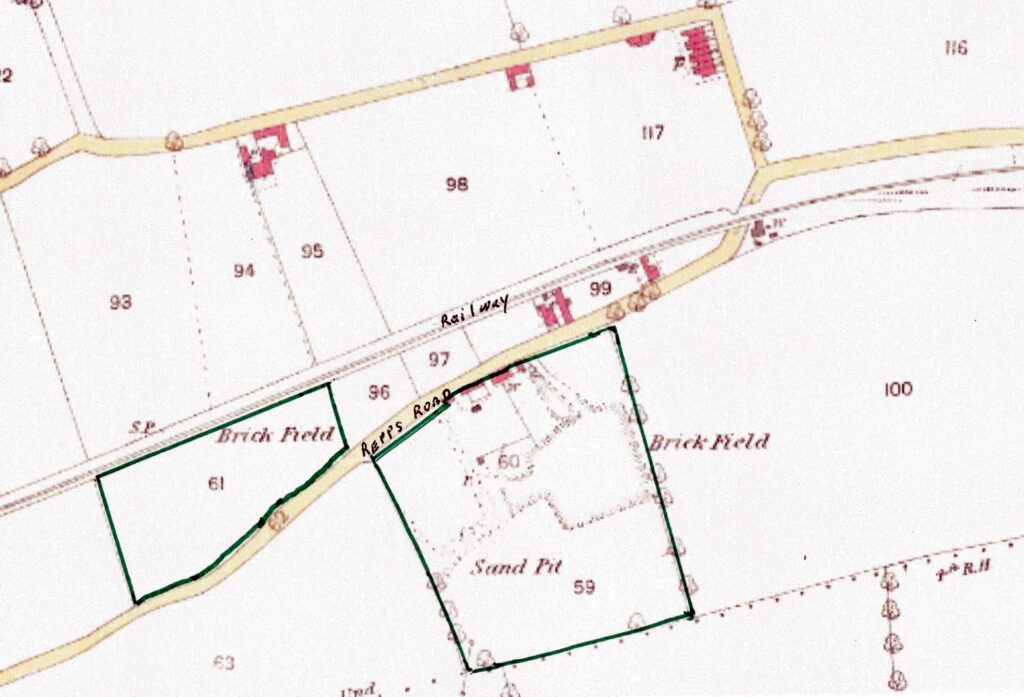

Shown in green on the main map at the top of this page this site was on the south side of Repps Road roughly where Bosgate Rise is today and opposite on the north side of the road. The large site is shown more clearly on the 1884 OS map below. Note: the railway opened in 1878 that seems to have provided a natural boundary on the north side.

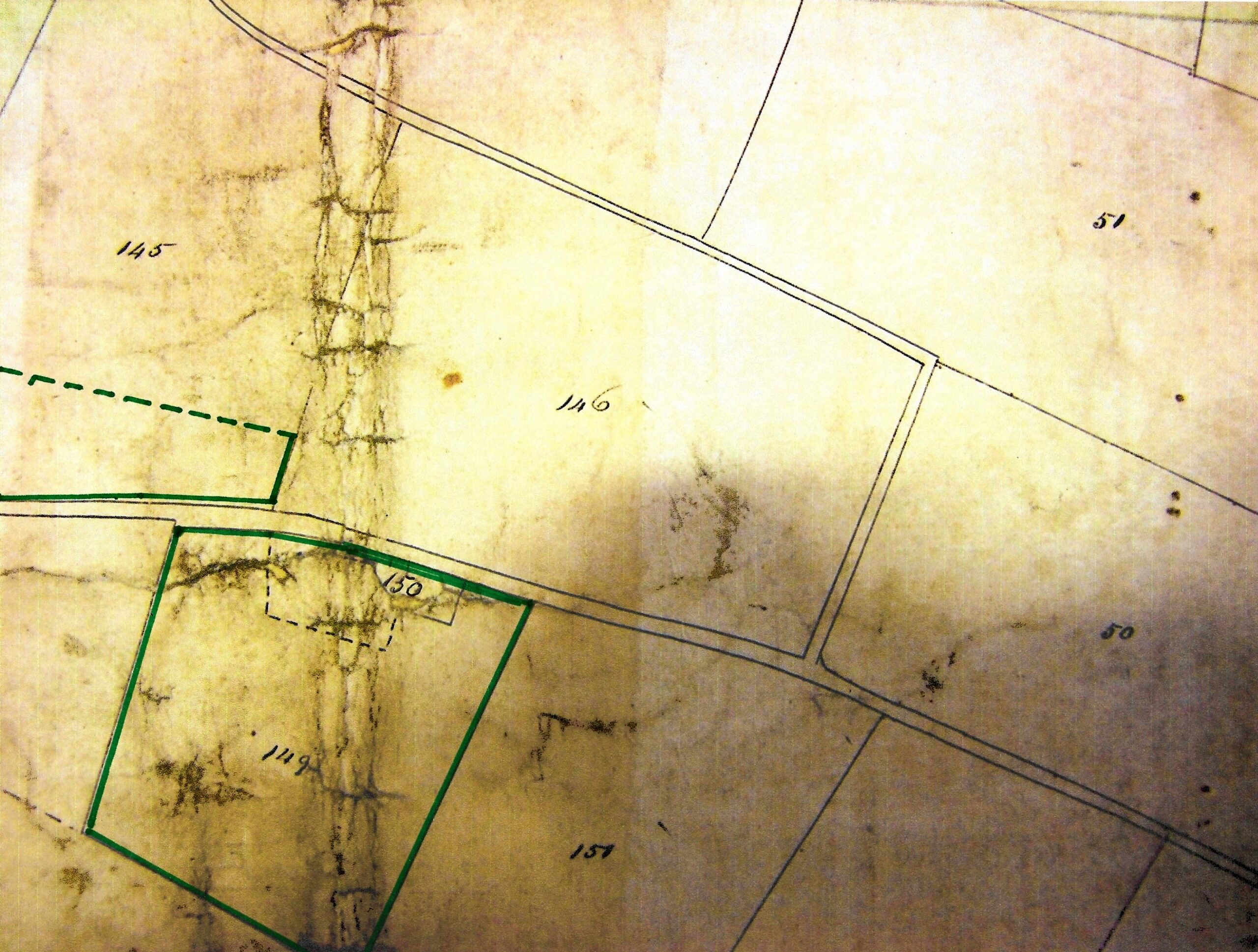

The Norfolk Archaeological Unit say there was a kiln on the south side of the site like the one at Chapman’s Pit brickworks but smaller. John Goose (1767-1847) was listed as the owner of the plot on the south side of Repps Road in 1842 according to the Tithe Award of that year. In 1842 the plots were numbered 149 & 150. Plot 149 measured four acres and 32 perches whilst plot 150 was listed as being a cottage and brick ground. John Goose was also listed as being a brickmaker in the 1836 & 1845 White’s Directories. By 1841 John was 74 and had retired and was living in Great Yarmouth. It is therefore possible that his son (1792-1879), of the same name, was living in the cottage and managing the brickworks although he is listed as a farmer in the 1841 census and his name may be the one listed in the 1845 White’s Directory.

In 1842 the plot on the north side of the road, No145, was owned by George Rising (1812-1860) a farmer and one of the landowning Rising family dynasty. The plot was not recorded as being in use as a brick field so perhaps this site was only developed after 1842. The map below shows a closer look at the land as recorded in the 1842 Tithe Award. The odd marks running through the plots are merely folds in the original map that is held in the Norfolk Records Office.

John Goose Jnr. died in 1879 and interestingly the 1891 census introduction page for District one mentions a brickyard called Gowen’s (Gown’s sic) on the south side of Repps Road. The business had changed hands and was owned by James Gowen (1827-1899) who had lived in Repps Road for many years and was listed as a brickmaker in the 1892 & 1896 editions of Kelly’s Directory. His main occupation was a market gardener so, like so many others, brick making was not his only job.

The site is also shown on the 1880 hand drawn map No9 shown below.

The 1906 OS map marks ‘Old Brick Kiln’ on the north side of the site with pits. The revision of the 1938 OS map shows no sign of the brickworks at either site.

8. Linford’s Brickyard, Black Street

Grid Reference: TG 4537 1834.

Norfolk Historical Environmental Record NHER(4) No 16666.

Shown in red on the main map at the top of this page and pinpointed in the same colour on the map above, this site of a former brickworks is better known to many locals as the former Kirby’s Yard that is now Oak Tree Close.

Moses Linford (1777-1839) inherited this land from his father, William Linford, in 1822. In his younger days Moses was a wheelwright and later became a carpenter and after 1822 he made good use of the land that had a 15ft thick seam of brick earth of the same quality as that at Bracey’s Hemsby Road site. In 1836 Moses appeared in White’s Directory as a brickmaker. Moses had a son called James (1815-1877) and he is listed in the 1842 Martham Tithe Award as being the owner of plot No691 a brick ground of 2 roods and 39 perches. James was also listed in White’s Directory of 1845 and the Post Office Directory of 1846 as being a brickmaker. And, again he features in the deeds of the cottage at 71 Black Street as being a brick manufacturer from 1847 to 1854. Although this must have kept him busy it was not his fulltime job as he was also a shop keeper in White Street. There was a brick kiln on the site in around 1852 when it was mentioned in an abortive auction advert. It seems likely that the bricks used in the restoration of St Mary’s from 1855/61 were made here as it was so close but no actual evidence has been found. After James died in 1877 the land was owned by a succession of absent investment owners but in the early years of the 20th century was firstly rented, and then purchased in 1911, by James Edwin Kirby (1863-1942). He had started out as a brick and salvage merchant and when the brick earth became exhausted it was his ancestors that turned the remaining pit into Kirby’s haulage and farming contractors yard.

It is not always clear when the various Martham brick grounds closed. The railway opened in 1878 and it has been suggested that this led to a decline in local brick making because cheaper mass-produced bricks could be brought in by rail. Conversely the biggest brick ground – at Ferrygate – was sold as a going concern in 1885. Other people say yards closed between the wars. Local man Bertie Murrell, who often contributes to the Facebook page ‘Memories of Martham’, told me that he worked for Harriss Builders of White Street in 1953 and can recall being sent to collect bricks from both Martham and Hemsby railway stations that had been made in Peterborough because none were made in Martham by that time and the mass produced bricks were cheaper than those that had been made locally.

Part C – Martham Properties Built of Norfolk Red Bricks.

In the past many buildings could be found in the village built with ‘Norfolk Reds’ made in Martham. Not many remain but those that do provide the best evidence of the industry and some show high quality workmanship. There are examples that go back to the 18th century when, as we have heard earlier, itinerant bricklayers would have visited a site to make the bricks and build a house or a terrace. The following are just a few examples of properties in the village that were built with local red bricks:-

These are some of the oldest surviving cottages in the village dating to the 16th century. They were originally timber framed homes built by yeoman farmers and were brick faced in the 17th century. The south end gable to No 60 is in the traditional English bond which alternates between stretcher and header courses. This is the oldest pattern and was commonly used from the mid 17th century to the 18th century. The front of No60 has a mixture of English and Flemish bond but was rendered until recent years and the original pattern may not have been particularly stylised if it was going to be covered in render.

Baptist Chapel, The Green

The existing chapel in the north west corner of The Green was built of red bricks donated by Robert Moore (1825-1885) the owner of the Ferrygate Lane brick ground next to the Staithe. The foundation stone was laid in 1879 and the chapel was opened in 1880. The bricks are laid in a Flemish pattern and are 9″ x 4.5″ x 2.5″ as shown below.

Barn Rear of 23 Black Street

This much overlooked small barn has been subject to many repairs over the years but original Norfolk red brick parts have been faithfully copied in Flemish bond pattern. The oldest bricks in this pattern are an irregular 8.75″ x 4″ x 2.25″ as shown below.

Bell Yard Cottages, White Street

If you want to see a grand mix of styles, including flint work, look at the rear of these cottages on the churchyard side where you can see not only early 18th century English and Flemish bond patterns but a mixture of both.

Brickfield Farm Barn, Staithe Road

This ancient red brick barn has a mixture of brick patterns but the main south facing side is predominantly English bond which dates it roughly from the mid 17th century to the 18th century by which time the more decorative Flemish bond became more popular. The brick size here is 9″ x 4.5″ x 2.5″.

Brooklyn House, The Green

This largely original house has English bond on the west side as shown below.

This was a fine example of a former listed 19th century yeoman farmer’s house built of quality Norfolk red bricks that were made in Martham. The house fronted the east side of White Street but sadly was allowed to be demolished in 2009 and was replaced by a completely incongruous terrace of eleven cottage-style tiny houses.

Farm Houses

The ready supply of quality bricks made in the village meant that a small number of farmers could show off their wealth by building or extending their homes with the use of Martham bricks in the mid 19th century. Examples that still stand are Manor Farm, Back Lane (Flemish bond); Grove House, Black Street (Flemish Bond) and Grange Farm, Common Road (older parts in English bond).

The original parts of the barn were built using Martham-made red bricks.

The west aspect has a mix of English bond and English garden wall bond which involves alternating courses of headers and stretchers. Specifically, it consists of three courses of stretchers between every course of headers. There are two areas, one near the top and one near the base of the wall, where three rows of stretchers have been used.

Both gable ends are in old English bond pattern. There are also elements of triangular tumbling-in which is a method of reducing height by using an inward sloping of the brick courses. The old English bricks on the south elevation are 9″ x 4.5″ x 2.5″

The east facing aspect has elements of old English bond pattern but (probably repaired) Flemish bond pattern as well.

The Lodge Gatehouse, White Street

The original part of this former gatehouse to Martham House shows fine Flemish bond craftsmanship and window arches. Built c1870.

Martham House, Threshing Barn, Pratts Loke.

This early built threshing barn originally belonged to Martham House and still stands at the time of writing (2023) in Pratts Loke, off Somerton Road. Planning permission was given in 2018 for the conversion of the barn into two dwellings. A good deal of repair and restoration has been carried out externally over the years but a closer look at the lower levels reveals English bond supporting a build date that has been estimated to around 1700. In the older sections the bricks are 9″ x 4.5″ x 2.5″ and were almost certainly made in Martham. See the pattern style on the east side shown below.

Moregrove Barns

Another early example of red brick barns is the pair at Moregrove. They stand on the north side of the site and are Grade II Listed (1987) probably built in the very early 19th century. High up inside the west gable end the name Benjamin Rising (1775-1835) is inscribed giving a good indication of the age of the buildings. The north side of the main barn has distinctive Flemish bond brickwork. The brick sizes are an unusual 7″ x 4″ x 2.25″ as shown below.

This elegant early 19th century house stands on the north side of The Green. In its time it has also been a shop. Built in Flemish bond.

Many of the houses on the north side of Repps Road including Nos 26, 30, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46, 48, 50, 58, 60, 62 & 64 were built using Martham red bricks. The terrace numbered 34 to 38 has particularly clear Flemish brickwork as have several others. Those from Southerly (No48 ) westwards are in reds but in the more modern continuous stretcher bond pattern.

Staithe Road Cottages ( 9 & 11), near junction with Black Street.

Not much is known about these cottages that were built in the mid 19th century as labourers cottages. In 1842 they were owned by Robert Beverley but occupied by a widow called Ann Reeve, nee Webster. At the time the cottages were built they would have been for farm workers and would have had to have rooms no smaller then 14ft x 14ft. Externally they show clear Flemish bond brickwork.

Built of Norfolk red bricks Westgrove is a substantial early Edwardian house set back from the east side of Rollesby Road. It was built in 1915 for Oliver Starling by local master builder Henry Futter.

Part D – Some Martham people associated with the trade.

Below is a table of people who worked in or were associated with the Martham brickmaking trade. It is not a comprehensive list of everyone involved as it was drawn up based on snapshots in time from census returns from 1841 to 1921; the 1939 Register; Trade Directories from 1836 to 1937; St Mary the Virgin baptism records from 1813 to 1920 that give the fathers’ employment details and similar marriage records; miscellaneous wills; Methodist Chapel baptism records from 1883 to 1902; the 1842 Tithe Award list and some personal reminiscences.

One example is John Page (1817-1873) who was the foreman of the bricklayers during the 19th century restoration of St Mary’s Church and is listed in both the 1868 Harrolds Directory and the 1869 Post Office Directory as well as the 1871 census as being a bricklayer of Black Street.

The list shows that a large number of men in the trade did not come from Martham. It is clear that they followed the availability of work or better pay and this is particularly so in the second half of the 19th century when building was at its peak in the village. Given their short stays in the village the numbers I have been able to record could well be understated because they came and went quickly and particularly between census years. Note how some were lodgers at the village pubs.

| Martham Brick Workers List | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surname | Forename | Date and place of birth | Address | Occupation | Source(s)* | Notes |

| Allison | Isaac William | 1856 at Norwich | Martham House Lodge, White Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 91c | |

| Blyth | Charles | Abt 1865 at Caister-on-Sea | Repps Road, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer | 81c | Brother of George William Blyth |

| Blyth | George William | 1847 at Caister-on-Sea | Repps Road, Martham | Bricklayer & Brick maker in 1883 | 81c; 83K & 01c | Brother of Charles Blyth |

| Bracey | William James | 1847 at Great Yarmouth | Cess, Martham | Brick manufacturer & merchant | 90K; 92K; 96K; 04K & 08K | He was also a builder & farmer |

| Braddock | Charles | 1811 at Martham | Somerton Road, Martham | Brick Maker | 46W; 46PO & 50Hu. | He was also a brewer and cooper. |

| Braddock | Daniel George | 1819 at Martham | Damgate, Martham | Bricklayer | 64W; 68Ha; 77K & 79K. | He was also a farmer and thatcher. |

| Brooks | Eldred Edgar | 1865 at Martham | Repps Road, Martham | Master bricklayer | 91c; 92K & 96K. | |

| Broom | Arthur William | 1868 at Martham | Damgate, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer | 81c | Aged only 13 in 1881 |

| Brown | Edward | Abt 1832 at Winterton-on-Sea | Trowel & Hammer PH, Repps Road, Martham | Brick maker | 51c | |

| Chase | John | Abt 1826 | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 41c | Aged about 15 |

| Cunningham | Charles Ives | 1855 at Ludham | Providence Yard, Black Street, Martham | Brick maker's labourer | 81c & 87bap | |

| Curtis | John Joseph | 1869 at Ingham, Norfolk | Martham House Lodge, White Street, Martham | Brick maker | 91c | Lodged with Allison family. |

| Dack | Alfred James | 1864 at Sheringham, Norfolk | Martham | Brick maker | 86mar & 98bap | |

| Dack | George Robert | 1842 at Hevingham, Norfolk | Providence Yard, Black Street, Martham | Brick maker | 73bap & 81c. | Father of Robert George Dack (1864) |

| Dack | Robert George | 1864 at Hevingham, Norfolk | Bracey's Buildings, Cess Road, Martham | Brick maker | 86bap & 91c | Son of George Robert Dack (1842) |

| Dack | William | 1840 at Hevingham, Norfolk | The Green, Martham | Brick maker | 71c | |

| Dawson | Edward | 1823 at Clippesby | Cess (1841 & 1851). Braddock's Cottages (1871). | Bricklayer & Brick maker | 41c; 51bap; 51c: 71K & 79K | Son of John Dawson |

| Dawson | John | 1785 at Filby | Cess, Martham | Bricklayer | 27bap; 41c & 51c | Father of Edward Dawson |

| Deary | John | About 1826 at Martham | Damgate, Martham | Brick maker | 90K | He was also a coal agent and thatcher. |

| Dove | Robert | 1862 at Martham | Repps Road, Martham | Brick maker | 86bap & 90bap. | |

| Duffield | Frederick Jellicoe | 1916 at Bradwell, GY | Rollesby Road, Martham | Bricklayer | 39r | |

| Durrant | Sidney | 1886 at Martham | Cess in 1921 & Damgate in 1939 | Bricklayer | 21c & 39r | Worked for Kirby Haulage Contractor |

| Empson (or Smith) | Esau William | See Smith, Esau William | ||||

| Felmingham | James | 1840 at Hemsby | Hemsby Road, Martham | Journeyman bricklayer | 61c; 62bap & 64bap | Son of John Felmingham b1804 |

| Felmingham | John | 1804 at Acle | Hemsby Road in 1861. Black Street in 1871. | Bricklayer | 31bap; 33bap; 35bap; 61c; 64W; 68Ha; 69PO; 71c; 77K & 79K. | Father of John & James Felmingham |

| Felmingham | John | 1838 at Hemsby | Providence Yard, Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 61c; 62bap; 68Ha; 69PO & 70bap. | Son of John Felmingham b1804. |

| Felmingham | Robert | About 1830 at Martham | Martham | Bricklayer | 59bap | Son of John Felmingham b1804. |

| Futter | George Edward | 1859 at Martham | Providence Yard, Black Street in 1871. Somerton Road in 1911 | Bricklayer's labourer | 71c; 04K; 08K; 11c & 12K. | Aged only 12 in 1871. |

| Futter | John | 1888 at Matham | Damgate, Martham | Bricklayer | 11c | |

| Goose | John | 1767 at Hempstead, Norfolk | Cess, Martham | Brick maker | 36w, 45w, 42t | |

| Gowen (or Gown) | George William Thomas | 1858 at Billockby. | Repps Road & Bosgate Hill, Martham | Brick maker | 90K | Son of James Gowen. Had a brick yard off Repps Road. |

| Gowen (or Gown) | James | 1827 at Clippesby | Repps Road, Martham | Brick maker | 92K & 96K | Father of George Gowen. Had a brick yard off Repps Road. |

| Grimmer | Edward Eingall | 1823 at Martham | Damgate in 1851. Cess 1871. White Street in 1891. | Jobbing bricklayer | 51c; 71c, 81c & 91c | Brother of Richard Grimmer |

| Grimmer | Richard | 1840 at Martham | Repps Road in 1871, Cess in 1881 & Black Street in 1891 & 1901. | Bricklayer's labourer | 71c; 81c, 91c & 01c | Brother of Edward Eingall Grimmer. |

| Gymer | Elijah | 1855 at Martham | Damgate, Martham | Brick maker | 81c | |

| Harriss | Phillip F. S. | 1913 at Fleggburgh | White Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 39r | |

| Haywood | Robert Richard | 1850 Martham | The Green, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer | 61c | Aged only 11 |

| Hillersdon | Silvanus Grove | 1816 at Barnes, Surrey | Moregrove, Martham | Clay pit tenant | 42t | |

| Julier | Albert Samuel | 1880 at Caister-on-Sea | Damgate, Martham | Bricklayer | 39r | |

| Kirby | James Edwin | 1863 at Martham | Black Street, Martham | Brick maker, builder & salvage merchant. | 71hd & 11c | |

| Knight | James | Abt 1811 at Acle. | Black Street, Martham | Master bricklayer | 51c | |

| Knights | John | Abt 1836 at Martham | The Green, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer | 51c | |

| Larner | George | Abt 1820 at Winterton-on-Sea | Repps Road, Martham | Bricklayer | 41c | |

| Leverick | Herbert Erasmus | 1863 at Nottingham | Bracey's Buildings, Cess Road | Journeyman bricklayer | 91c & 92bap | |

| Linford | James | About 1815 at Martham | Black Street, Martham | Brick maker & merchant | 45Wh, 46PO & 76hd. | Son of Moses Linford |

| Linford | Moses | 1777 at Martham | Black Street, Martham | Brick maker | 36w & 71hd. | Father of James Linford. |

| Linford | Samuel | 1812 at Martham | Cess, Martham | Brick maker | 51c & 54bap | |

| Mason | Frank Oswald | 1886 in Martham | Cess & Black Street, Martham | Brick maker | 1908bap; 1910bap & 21c | Worked for Julius Starling brick maker of Repps. |

| Monsey | Ernest | 1868 at Ormesby St Michael | Lodged at Cess, Martham | Journeyman bricklayer | 01c | |

| Moore | Robert | 1825 at Martham. | The Green, Martham | Brick maker | 77K & 83K. | He owned Ferrygate Staithe brick ground. |

| Myhill | Robert | Unknown | Unknown | Brick maker | 92K & 96K | |

| Nichols | Jonathan | 1860 at Hemsby | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 01c | |

| Page | John | About 1817 at Great Yarmouth | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 68Ha; 60PO & 71c | Father of John & Nathaniel Page |

| Page | John Charles | 1842 at Great Yarmouth | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 71c | Son of John Page (1817) |

| Page | Nathaniel Richard | 1850 at Great Yarmouth | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 71c; 71bap & 73bap. | Son of John Page (1817) |

| Palmer | Herbert Ernest | 1871 at Stokesby | Clarke's Farm, Staithe Road, Martham | Bricklayer | 01c | |

| Palmer | Herbert Ernest | 1871 at Stokesby, Norfolk | Martham | Bricklayer | 1900bap | |

| Piggin | George | 1823 at Ormesby St Margaret | Martham. | Bricklayer | 55bap | |

| Piggin | John | 1817 at Ormesby St Margaret. | Repps Road, Martham | Bricklayer | 41c & 50bap | Son of Thomas Piggin |

| Piggin | Thomas Dawson | 1796 at Filby | Repps Road, Martham | Bricklayer | 41c; 45PO; 46PO; 50Hu; 51c; 54W; 61c; 64W; 68Ha & 69PO. | Father of John Piggin |

| Pitchers | Charles Albert | 1872 at Martham | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer | 01c | |

| Platten | William Jonathan | 1869 at Rollesby | Damgate Corner, Martham | Bricklayer | 39r | |

| Powles | Walter Charles | 1874 at Winterton-on-Sea | 8 Somerton Road, Martham | Bricklayer | 39r | |

| Proctor | Thomas Bartlett | 1826 at Martham | Somerton Road, Martham | Bricklayer | 51c | |

| Reeve | Henry Webster | 1834 at Repps | Trowel & Hammer PH, Repps Road, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer | 51c | Brother of John Reeve b1830. |

| Reeve | John | 1830 at Repps | Cess, Martham | Bricklayer | 51c | Brother of Henry Webster Reeve b1834. |

| Ribbands | Samuel Charles | 1857 at Horsford, Norfolk | Martham or West Somerton | Brick maker | 79bap, 80bap; 86bap & 88bap. | |

| Riches | William | 1852 at Surlingham, Norfolk. | Bracey's Buildings, Cess Road | Brick maker | 91c | |

| Rouse | John William | 1857 at Hemsby | Bracey's Buildings, Cess Road | Brick maker | 88bap & 91bap | |

| Secret | Charles | 1804 at Heatherset | Damgate, Martham | Brick maker | 41c | From Heatherset |

| Self | Frederick Robert | 1882 at North Walsham | White Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 11c & 21c | |

| Shreeve | Arthur William | 1871 at Hemsby | Somerton Road, Martham | Brick maker | 01c | |

| Shreeve | James | 1844 at Rollesby. | Martham. | Brick maker | 84bap & 86bap | |

| Smith | Henry | 1846 at Ashby Sy Mary, South Norfolk | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 91c | Stepfather of Esau W Smith (Empson) |

| Smith (born Empson) | Esau William | 1865 at Sea Palling | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 91c | Step son of Henry Smith |

| Starkings | William Samuel Anguish | 1867 at Ludham. | Cess, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer | 81c; 1903bap; 1904bap & 1907bap. | Aged only 13 in 1881 |

| Sutton | George Robert | 1917 at Martham | Fern Cottage, Staithe Road | Bricklayer | 39r | |

| Tooke | Albert Ernest | 1874 at Fleggburgh | Mustard Hyrn, Cess, Martham | Bricklayer | 01c | |

| Tooke | Albert Ernest | 1874 at Fleggburgh | Lodged at Mustard Hyrn | Bricklayer's labourer | 01c | |

| Trivett | Harry Augustus | 1872 at Hevingham | The Green, Martham | Bricklayer | 11c | |

| Turner | Robert | 1817 at Upton, Norfolk | Providence Yard, Black Street | Brick maker's labourer | 71c | Father of Robert Joshua Turn b1854 |

| Turner | Robert Joshua | 1854 at Upton, Norfolk | The Green, Martham | Brick maker | 81c | Son of Robert Turn b1817 |

| Tyce (or Tice) | John | About 1806 (place unknown) | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 41c | |

| Tyce (or Tice) | John | 1775 at Martham | Black Street, Martham | Bricklayer | 45Wh & 46PO. | |

| Utting | Jack | 1921 at Martham | Ivydene, The Green | Apprentice bricklayer | 39r | |

| Utting | Richard Wilson | 1892 at Great Yarmouth | 'Bruce Rock', Repps Road | Bricklayer | 39r | |

| Watson | Elijah John | 1865 at Martham | Repps Road, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer in 1881. Brick maker in 1887. | 81c & 87bap | Brother of George Samuel Watson |

| Watson | Ernest Albert | 1896 at Martham | Repps Road, Martham | Bricklayer's labourer | 39r | |

| Watson | George Samuel | 1863 at Martham | Repps Road, Martham | Brick maker's labourer | 81c | Brother of Elijah John Watson |

| Watson | Walter Robert | 1891 at Martham | 1 Hemsby Road, Martham | Bricklayer | 91bap & 39r | Nephew of Elijah John Watson |

| Watson | Walter William | 1866 at Martham | Cess, Martham | Brick maker | 97bap | |

| Wright | James | About 1789 at Ringland, Norfolk | Repps Road. Linford Cottages in 1871. | Bricklayer | 16bap; 20bap; 26bap; 36W; 41c; 46K; 50Hu; 51c; 54W; 61c; & 71c. | He was also the landlord of the Trowel & Hammer PH |

| Wright | James | About 1811 at Acle. | Black Street in 1851. White Street in 1861. | Bricklayer | 50Hu; 54W; 64W; 68Ha & 69PO. | |

| Youngs | Edward | 1831 at Moulton St Mary | Repps Road in 1868. Rollesby Road in 1877. | Bricklayer | 68Ha; 69PO; 71c; 77K; 83K & 91c. | He was also the landlord of the Victoria Inn. |

| Youngs | James Alfred | 1858 at Martham | The Green in 1881 & 1891. Black Street in 1911. | Bricklayer | 81c, 90K; 91c & 11c | By 1890 he was also a builder. |

| *Sources: | |

| 16bap | 1816 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 20bap | 1820 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 23bap | 1823 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 26bap | 1826 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 27bap | 1827 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 31bap | 1831 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 33bap | 1833 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 35bap | 1835 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 36W | 1836 White’s Directory |

| 41c | 1841 census |

| 41c | 1841 census |

| 42t | 1842 Tithe Award |

| 45PO | 1845 Post Office Directory |

| 45W | 1845 White’s Directory |

| 46K | 1846 Kelly’s Directory |

| 46PO | 1846 Post Office Directory |

| 46W | 1846 White’s Directory |

| 50Hu | 1850 Hunt’s Directory |

| 50bap | 1850 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 51c | 1851 census |

| 51bap | 1851 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 54bap | 1854 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 54W | 1854 White’s Directory |

| 55bap | 1855 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 59bap | 1859 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 61c | 1861 census |

| 62bap | 1862 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 64bap | 1864 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 64W | 1864 White’s Directory |

| 68Ha | 1868 Harrold’s Directory |

| 69PO | 1869 Post Office Directory |

| 70bap | 1870 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 71c | 1871 census |

| 71K | 1871 Kelly’s Directory |

| 71bap | 1871 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 71hd | House Deeds for 71 Black Street |

| 73bap | 1873 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 77K | 1877 Kelly’s Directory |

| 79K | 1879 Kelly’s Directory |

| 79bap | 1879 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 80bap | 1880 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 81c | 1881 census |

| 83K | 1883 Kelly’s Directory |

| 84bap | 1884 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 86bap | 1886 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 86mar | 1886 St Mary the Virgin marriage register |

| 87bap | 1887 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 88bap | 1888 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 90K | 1890 Kelly’s Directory |

| 90bap | 1890 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 91c | 1891 census |

| 91bap | 1891 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 92K | 1892 Kelly’s Directory |

| 92bap | 1892 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 96K | 1896 Kelly’s Directory |

| 98bap | 1898 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 1900bap | 1900 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 01c | 1901 census |

| 1903bap | 1903 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 04K | 1904 Kelly’s Directory |

| 1904bap | 1904 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 1907bap | 1907 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 08K | 1908 Kelly’s Directory |

| 1908bap | 1908 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 1910bap | 1910 St Mary the Virgin baptisms register |

| 11c | 1911 census |

| 12K | 1912 Kelly’s Directory |

| 21c | 1921 census |

| 39r | 1939 register |

The table below is based on the number of people working in the trade that were born in Martham or elsewhere by decade. It also highlights the peak in the numbers involved over the decades.

| No of Brick Industry Workers by Decade | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Decade | Martham born | Born elswhere | Total |

| 1810's | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1820's | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 1830's | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 1840's | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| 1850's | 6 | 10 | 16 |

| 1860's | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| 1870's | 8 | 10 | 18 |

| 1880's | 9 | 13 | 22 |

| 1890's | 8 | 12 | 20 |

| 1900's | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| 1910's | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| 1920's | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 1930's | 5 | 6 | 11 |

References:

- 1812 Martham Enclosure Award and Map. Norfolk Records Office. Ref PC125/9.

- 1842 Martham Tithe Award. Norwich Records Office. DCN 127/38. Copy of tithe map, in 2 parts.

- Tom Williamson. The Norfolk Broads – A Landscape History (1997).

- Norfolk Historical Environmental Records. Comprehensive records of the historic environment of the county of Norfolk.

- This map is based on the 1884 Ordnance Survey six inches to the mile map but zoomable as an overlay courtesy of the National Library of Scotland (www.nls.uk).

- This map is based on the 1907 published Ordnance Survey six inches to the mile map but zoomable as an overlay courtesy of the National Library of Scotland (www.nls.uk).

- NIAS – Norfolk Industrial Archaeological Society. www.norfolkia.org.uk.

Other sources, help and advice:

- Ann Meakin – Martham historian. The Mystery of the Martham Flint Houses.

- Yarmouth Archaeology 2005, page 60. Plus, other advice and help.

- Benfleet Community Archive. www.benfleethistory.org.uk

- Brick Making History. www.historicengland.org.uk

- History of Bricks and Brickmaking in Britain. Brick making / Heritage Crafts.

- Norfolk Archaeological Unit.

- Norfolk Records Office.

- Peter Henry Emerson (1856-1936). British writer and photographer.