1812 Martham Inclosure Award

Inclosure was the legal process in England of consolidating (inclosing) small landholdings that had existed since the 13th century into larger farms. Once ‘Inclosed’, use of the land became restricted and available only to the owner and it ceased to be available for communal use. One reason for doing this was to increase food production. Before the Inclosure there were narrow strips of land that poor farmers tended. In Martham these existed mainly in the area north of Sandy Lane. There was also open common land that farmers would use to graze animals; in Martham this was mainly north of Common Road off Cess. This old system discouraged improvement and favoured the small-time farmers.

There is little doubt that Inclosure led to improved efficiency of the use of land and greater yields to feed a rising population. The irony is that it drove many poor villagers into poverty and fuelled the start of emigration. On the social side, the rich became even richer and distinct class gaps emerged. But, setting the ethics to one side the outcome of the process was of great use to present day historians and genealogists for three reasons: (1) those who wanted to be awarded land had to apply giving details of their existing land holdings; (2) the written Award describes the parish by giving details about land and roads etc, and (3) the accompanying Award map shows properties and in many cases refers to plot numbers mentioned in the Award.

The map that accompanies the Award is the earliest map for Martham that shows the existence of buildings linked to their owners and/or occupiers. It shows ownership of land by individuals, churches, schools and charities, as well as roads, drainage and land boundaries. It was not particularly drawn up to identify properties but does indicate buildings as little black blocks. You can see a pdf of the 1807 empowering Act that gave rise to the Martham 1812 Inclosure Award by clicking HERE.

Process

Once the Act had been passed Commissioners were appointed to implement it. They advertised and held meetings inviting landowners to make claims based on their existing ownership. On 12th November 1807 the Commissioners issued a list of the people that had made claims. Any person who wished to object to the claims that had been made had to do so before 28th November 1807. Below is a table setting out the actual claimants in alphabetical name order.

| 1812 Inclosure Award alphabetical claims list | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Surname | Forename | Claim No. | Notes |

| Bane | James | 54 | |

| Barber | Elizabeth | Late claim | |

| Benslin | Rebecca | 57 | & Mary Boult |

| Benslin | Rebecca | 71 | Widow |

| Beverley | John | 68 | died 1835 aged 61 |

| Boult | Mary | 57 | & Rebecca Benslin. Wife of Wm. Boult. |

| Boutell | Charles | Late claim | Reverend. |

| Brunson | William | 85 | died 1847 aged 91 |

| Bushell | William | 30 | died 1823 aged 55 |

| Carrier | John | 63 | |

| Chapman | Robert | 78 | died 1841 aged 83 |

| Church | John & Robert | 48 | |

| Church wardens | 16 | ||

| Cobb | John | 25 | |

| Cockrill | Daniel | 82 | |

| Conyard | Lucy | 4 | Wife of Ben |

| Cookson | Eliza | 8 | |

| Crane | Thomas | 75 | died 1833 aged 75 |

| Crane | Thomas (Jnr) | 39 | |

| Creasey | Diana | 9 | |

| Creasey | William | 10 | Executors of |

| Creasey | William | 21 | Executors? |

| Davey | William | 83 | died 1814 aged 62 |

| Deary | Sarah | 29 | died 1842 aged 81 |

| Ditcham | Samuel | 87 | died 1822 aged 71 |

| Dixon | Thomas | 36 | |

| Docking | George | 14 | |

| Drake | Eleanor | 80 | Wife of Daniel |

| Dunt | Aaron | 46 | |

| English | Elizabeth | 40 | Widow died 1811 |

| Ensor | John | Late claim | |

| Fairweather | William | 32 | died 1811 aged 77 |

| Faulkner | John | 77 | |

| Francis | Thomas | 51 | + William Rising. Tithe Barn. |

| Francis | Thomas | 60 | (1743-1837) |

| Gallant | Robert | 5 | |

| Garnham | William | 74 | |

| Gedge | William | Late claim | |

| Goose | John | 3 | |

| Gray | Elizabeth | 43 | Wife of Johnathan |

| Greenacre | John | Late claim | |

| Grimson | Aaron | 13 | |

| Grove | Thomas | 45 | of Martham Hall |

| Harrison | William | 65 | Windmill |

| Hill | Robert | Late claim | |

| Hindle | Nathaniel | 33 | |

| Huggins | William | 20 | |

| Huntingdon | John Barker | 90 | of Burnley Hall, East Somerton |

| Jeffrey | John Gifford | 23 | |

| Le Nain | John | 38 | |

| Ledgett | Mary | Late claim | |

| Linford | Robert | 42 | Plus his brothers |

| Linford | William | 26 | |

| Littleboy | Sarah | 76 | |

| Lusher | Thomas | 19 | died 1810 |

| Mades | Edmund | 31 | of Rollesby Hall |

| Manship | John | 47 | |

| Manship | William | 69 | |

| Mitchells | John | 17 | |

| Moore | John | 34 | |

| Moore | William | 35 | |

| Moxon | John | 81 | |

| Parker | Alexander | 64 | died 1830 aged 65 |

| Petingell | Harber | 24 | |

| Pettigal | William | 88 | |

| Pollard | John | 72 | |

| Pollard | Mary | Late claim | |

| Pollard | William | 79 | |

| Pollard | William | 89 | |

| Porter | Robert | 22 | |

| Powles | Robert | 44 | |

| Powley | Christmas | 73 | died 1828 aged 72 |

| Proctor | Francis | 37 | died 1810 aged 72 |

| Ransome | Robert | 28 | |

| Rector of Burgh | 52 | Dr. Ord | |

| Reynolds | Francis Ridell | 50 | Kings Arms PH |

| Rising | Benjamin | 11 | |

| Rising | Robert | 7 | |

| Rising | Thomas | 2 | |

| Rising | Thomas | 62 | |

| Rising | William | 56 | of Someton Hall |

| Rogers | William | 6 | |

| Savoury | Anthony | 86 | died 1807? |

| Sowells | Daniel | 58 | |

| Thorton | Sarah | 84 | |

| Tice | John | 12 | |

| Trustees of Martham School | 55 | ||

| Vale | Henry | 1 | |

| Vincent | Richard | 67 | |

| Ward | Robert | 18 | died 1829 aged 80 |

| Warner | Mary | 41 | |

| Warner | Richard | 70 | died 1814 aged 73 |

| Watson | Clement | 59 | |

| Watson | John | Late claim | |

| Watson | William | 53 | |

| Wells | William | Late claim | |

| Whitaker | William | 61 | or Whittaker |

| Whittingham | Paul | 66 | Reverend. Parsonage. |

| Wilson | George | 27 | died 1834 aged 86 |

| Womack | Susanna | 49 | Wife of Arthur of Somerton |

| Woods | William | 15 | died 1830 aged 67 |

The Commissioners then had the long and complex task of sorting out the claims and how the land would be redistributed to agreed claimants.

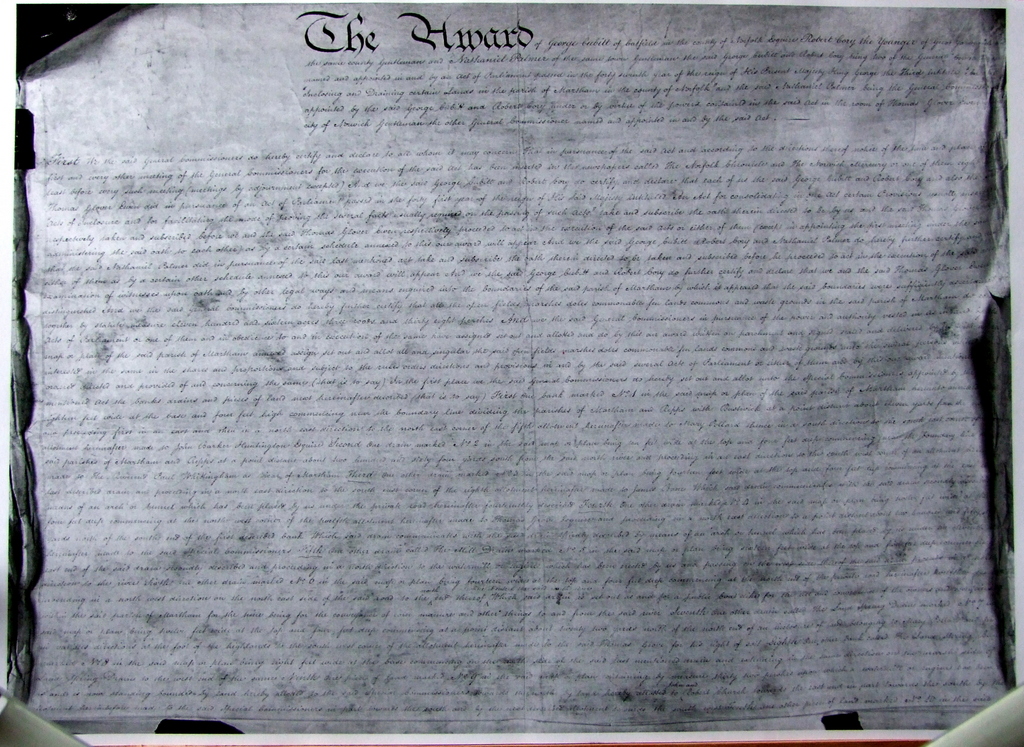

Once completed the Commissioners wrote a very long and detailed document setting out their decisions about who owned what. There are 47 pages of very small, close written text. Each page is about A3 size and is difficult to display and read on a computer so I have produced one here for reference and if you are really interested I would suggest going to the Norfolk Records Office to view it as a hard copy. A summary of the beginning of the Award was produced for the Commissioners that covers roughly the first five pages of the Award document and you can see it by clicking HERE.

Of more interest is the Award map which needs reading in association with the claims list. Sadly, the map (again at the Records Office) is in poor condition and being about three-foot square on parchment is not easy to view. I have photographed it as best I can, in sections, and it can be viewed in the gallery below the next paragraph.

Snippets

- Inclosure is the old-fashioned way of spelling Enclosure.

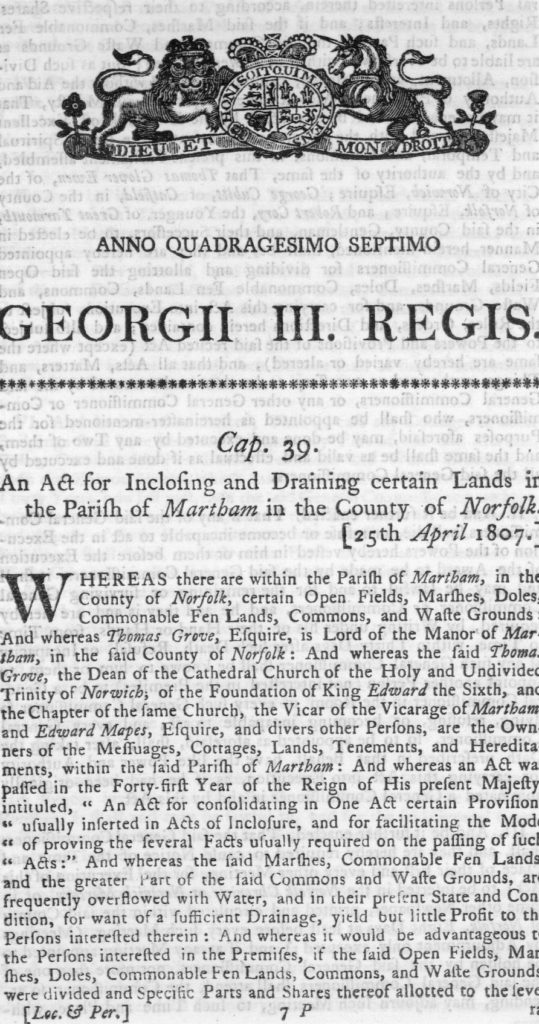

- The 1812 Award was enacted under an Act of Parliament passed in 1807 during the reign of King George III. The Act was for the inclosing and drainage of certain lands in the Parish of Martham.

- The Award is held under reference PC125/9/2 at the Norfolk Records Office next to County Hall.

- The Commissioners appointed were Thomas Glover Ewen Esq. of Norwich, George Cubitt of Catfield, Robert Cory the Younger of Great Yarmouth and Nathaniel Palmer of Great Yarmouth.

- The Commissioners determined that the boundaries of Martham measured 1,116 acres, 3 rods & 38 perches.

- The Award mentions the Rev. Paul Whittingham as being the Vicar of Martham at the time.

- Thomas Grove is listed as the owner of a private road number 1 which we now know as Hemsby Road and at that time was the main road to the south of the village green. The one crossing the middle of the green did not exist then.

- The Award lists 20 roads which were all described as being private. (No Highways Authority in those days).

- The Award mentions an old enclosure of land called Mill Close owned and occupied by James Bane and also William Wells as owner of the mill. (This is land at the top of Hemsby Road beyond the Council houses where there was once two windmills).

Photographs

Click a thumbnail for a close-up. Use the back button on your browser to return to this page.

Here follows a detailed analysis of the Act and how it applied at Martham, written by Ann Meakin to whom I am grateful for providing such a wonderful amount of information.

“The Act for Inclosing and Draining certain Lands in the parish of Martham, 1807”

During a study of the claims made to the General Commissioners at the time of “An Act for Inclosing and Draining certain Lands in the parish of Martham, in the County of Norfolk” in 1807, I made some interesting discoveries.

Martham was one of the parishes bordering on the Rivers Bure, Ant and Thurne where enclosure (or Inclosure) of the common land was rather more complicated than in other places. This was because enclosure involved an extensive project to strengthen the banks of those rivers and drain the marshes alongside them. It was therefore necessary for the Enclosure Commissioners to oversee the work and ensure its maintenance in the future.

It was during the time of the Napoleonic Wars between England and France when shipping in the English Channel was almost totally disrupted that the government realised it would be necessary to ensure that the United Kingdom was as self- sufficient as possible in food production. If the marshes bordering the rivers of east Norfolk were drained, it was thought that there would be considerable additional acreage of arable land available for food production. Drainage could not be done in a hurry. At Martham there were numerous wide drainage channels to be dug and a wind pump to be constructed to pump the water from the drainage channels up to the River Thurne. For each parcel of land awarded under the Inclosure from the area which had been the common grazing land, ditches had to be dug to mark its boundaries

In addition, it was also realised that in many places the ancient method of open field arable farming was no longer economical and steps were taken to phase it out in favour of creating fields, surrounded by hedges, belonging to individual farmers. At Martham, there were still extensive areas of open fields although many hedged fields were already in existence. Some land owners had fields which they wished to exchange for others, presumably in more convenient situations. The planting of hedges, which were of hawthorn around former open fields, took some time to complete. It is therefore not surprising that the Inclosure Act took five years to implement.

Martham, on what had once been the Island of Flegg had an upland area of sandy loam covered many millennia ago with “loess” deposited by strong winds, making it extra fertile for arable farming. On the northern edge of the parish alongside the River Thurne was a vast area of wet and dry common at more or less sea level but subject to flooding if the river overflowed. This can be seen on the accompanying copy of an extract from Faden’s Map published in 1797.

The common was used for grazing and numerous other purposes such as the turf cutting and a supply of firewood. This common land belonged to the Lord of the Manor who kept careful control over it to ensure that it would be maintained in a useable state for the various functions it provided and that it was not overgrazed. Many parishioners had various rights over it. The actual soil in many places was the sort of sandy clay that was ideal for brick making.

Before the Award of land could be considered, land owners who wished to make a claim for a part of the common had to explain in detail exactly what they already owned and a document was drawn up giving “A STATE OF THE CLAIMS”. Only those who held their land as freeholders, copyholders or leaseholders were considered to be eligible to make claims. The claims were to be taken into consideration at a special meeting on 30th November [1807] at the Kings Arms (the local public house) before queries could be considered and resolved and allocation of the awarded land could be authorised by the Commissioners.

A document was printed detailing the claims made by the 90 landowners concerned – 77 men and 13 women – not all of whom appeared to live in the parish.

From this document I made a detailed analysis of the claims and was amazed to discover the wealth of information obtained. In addition I copied the Ordnance Survey 6” scale maps of 1884 in order to show on it as accurately as possible the land inclosed and awarded and was surprised to realise that almost all of the field boundaries created at the enclosure still existed.

Analysis revealed that 64 of the claimants appeared to occupy part or all of the property they claimed whereas the property of the remainder was let to tenants.

The claims had to be signed by either the claimant or the person acting on their behalf. The claimants themselves signed 57 of the claims, indicating that nearly all were literate people. All claimed “a right of common pasture for all his commonable cattle levant et couchant upon the said commons and waste grounds in the said parish of Martham, at all times in the year.”

To find so many female landowners was a surprise. From searching the Parish Registers I discovered that of the 13, Sarah Deary, Elizabeth English and Rebecca Benslin were widows. Lucy Conyard, Mary Warner, Elizabeth Gray, Eleanor Drake and Mary Boult were married, Eliza Cookson, nee Creasey and Diana Creasey both lived in London and had inherited their land from their father William Creasey, Sarah Littleboy appeared to be unmarried. Of the other two I could find no information. When the awards were made, it was the husbands of the married claimants who were awarded the land.

The Inclosure “State of the Claims” described dwellings as houses, messuages or cottages. This proved interesting. I counted eight houses, 52 messuages and 77 cottages some of which were described as ‘double cottages’ but there were no further details about how each category was defined.

There were 42 barns listed, which in those days would have been threshing barns. It seems therefore that there may have been about 40 farms as in some cases more than one barn was listed by a claimant.

There were 36 stables listed. Did this indicate roughly the number of horses owned in the parish? Horses were precious animals. The farmers who owned large acreages had more than one stable but some people who owned only small acreages of land had a stable which may indicate that some horses were kept for riding and domestic use as well as for farm work.

There were 33 outbuildings listed. These included buildings such as shops, and blacksmith’s shops, a windmill and granaries and a ‘baking office’. By this time there were numerous craftsmen and tradesmen living in the parish, even though this was not evident from the claims made. The Parish Baptism Register gives details of the ‘professions’ of the fathers of children baptised from 1813 onwards recording a variety of occupations. It is possible that their workshops were part of their living quarters or that they were tenants.

There were 26 yards, 36 gardens and 4 orchards. Moregrove Manor held a fishery which was probably the one they held from Cobham College and was near to what is now Common Road staithe on the Thurne.

The Lord of the Manor owned the Boat Dyke Staithe at Ferrygate.

The tenure of land-holding was extremely complicated because nearly all the claimants had some pieces of land that were freehold and other pieces that were copyhold. There were 93 freeholdings. Other land was leasehold from the Dean and Chapter of Norwich Cathedral and comprised the Rectorial Tithes. Other pieces of land were copyhold, presumably of the Manor of Martham, however there was also the Manor of Moregrove and Knightleys and a small amount of land was copyhold of the Manor of Scratby Bardolph. Many of the records until 1928 of the Manor of Martham survive, as do some of those of Scratby Bardolph but those of Moregrove and Knightleys appear not to be traceable.

Before 1066 Martham Manor was held by the Bishop of Elmham and was passed on through the changes in the Bishopric to the Priory of Norwich until the Dissolution of the Monasteries after which it passed into private hands. Moregrove Manor was always held privately. When the ‘Domesday Book’ was compiled Martham had about 43 free men. Is it possible that the freeholders of 1807 held land that had passed down in that way for over 700 years!

Discovering that several of those who made claims in 1807 were still alive in 1842 when the Tithe Commutation document was made, it was possible from studying the Tithe and Inclosure Maps to discover where they lived. A few had died and their properties had passed on to their heirs or had been sold to others. From this information, I was also able to identify the very few buildings which have survived to the present day even though they have been drastically altered or extended. It is remarkable that farm buildings have survived longer than dwellings. There are still a few magnificent threshing barns standing around the village.

For some claimants I could find no award of land. It is possible that for some, the cost of registering an award was too high. For each award made, a payment was required to cover the cost of the legal fees, the cost of the parchment on which the title deed would be written and the cost of stamp duty. For one piece of land awarded, near where they lived the claimants were required to £1 11s. 6d. That sort of cost may well have been prohibitive for those who owned only a very small amount of land and were on the verge of poverty.

The Award, effective from 12th June 1812 is an enormous document written on 47 pages of parchment. It is very cumbersome to handle and difficult to read with very long lines of handwriting. Therefore it needs very careful concentrated scrutiny to be sure of acquiring the correct information. Some of the detail on the map is very hard to decipher without magnification. There is still much research to be done on this most fascinating and interesting topic.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

A copy of A ‘STATE OF THE CLAIMS Delivered to the General Commissioners named and authorised, in and by an act of Parliament passed in the 47th year of the reign of His Majesty King George the Third, entitled, “An Act for Inclosing and draining certain Lands, in the Parish of Martham, in the County of Norfolk”’ is included in a large green book kept in Martham Branch Library.

Martham Enclosure Award and Map are held at the Archive Centre, Norwich. N.R.O. Reference PC 125/9/1