Martham Manor (Prior’s Manor), Hall Road, Martham

This page could not have been written without the incredible information provided by Barbara Cornford and her book “Medieval Flegg” which is a must read for anyone interested in the history of Flegg from 1086 to 1500.

This page also contains information about the Lords of the Manor and The Hall at Hall Road.

There were two Manors in Martham. One was the small Manor of Moregrove to the north of the village and the other, larger one, was the Prior’s Manor to the south of the village centred at what we now know as Hall Road. It has a recorded history stretching back for over 900 years.

11th & 12th Centuries

In the mid eleventh century, at the time of Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), all the land in England was owned by the King. He gave vast tracts of land to his highest-ranking courtiers, knights and bishops. The Bishops of Elmham held most of Norfolk and Suffolk from the King. At that time the most important town in East Anglia was Thetford and the head of the church there was William De Beaufeu, Bishop of Elmham.

In 1090 Bishop Herbert de Losinga succeeded Bishop Beaufeu. In 1094 Bishop Losinga transferred his seat of ecclesiastical governance from Thetford to Norwich which had become the principal town of the diocese. At Norwich he founded the Cathedral Priory monastery and started building Norwich Cathedral in 1096. At the same time, he converted his rights of patronage over lands in Norfolk and Suffolk into those of a Lord of the Manor. The monks at his new Priory Cathedral needed financial support and so he gave the Manor of Martham, the church of St Mary the Virgin and a great deal of other land in East Anglia to his new priory. It is doubtful that Bishop Losinga ever came to Martham but the Martham Manor helped to provide for the needs of the monks of the Cathedral Priory.

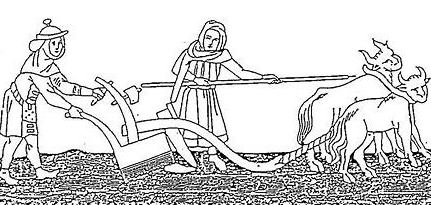

The Domesday Book of 1086 tells us that Martham was unusual in that it had a relatively high number of freemen at 36 who were men that owned land but still had some obligation to the Lord of the Manor which in this case was the Bishop. Their feudal obligations may have been fairly light, being something like extra hands at harvest time and having to give a part of what they produced like wheat, lambs or geese to the Lord. In some cases, it was advantageous for them to be aligned with a Lord to come under his protection. In addition, in 1086 there were only 7 villeins and three temporary boarders from elsewhere that would have worked directly on the Manor. Land held by the Priory at any Manor was known as the ‘demesne’ and at Martham consisted of about 600 acres of cultivated land and 50 acres of meadow which was larger than any other estate in Flegg. None of the clergy of the Priory ever lived in Martham and did not concern themselves with the day-to-day running of the estate. The demesne was managed by a steward and the rents and produce went to support the Priory at Norwich. Wheat and barley was grown and went to the Priory for making bread and beer. The estate had two ploughs, each with a team of eight oxen. The monks were also provided with peat turves from the Manor to be burned on the Priory’s open hearths. This was cut from the marshy area of fen to the south of the Manor next to what is now Rollesby Broad.

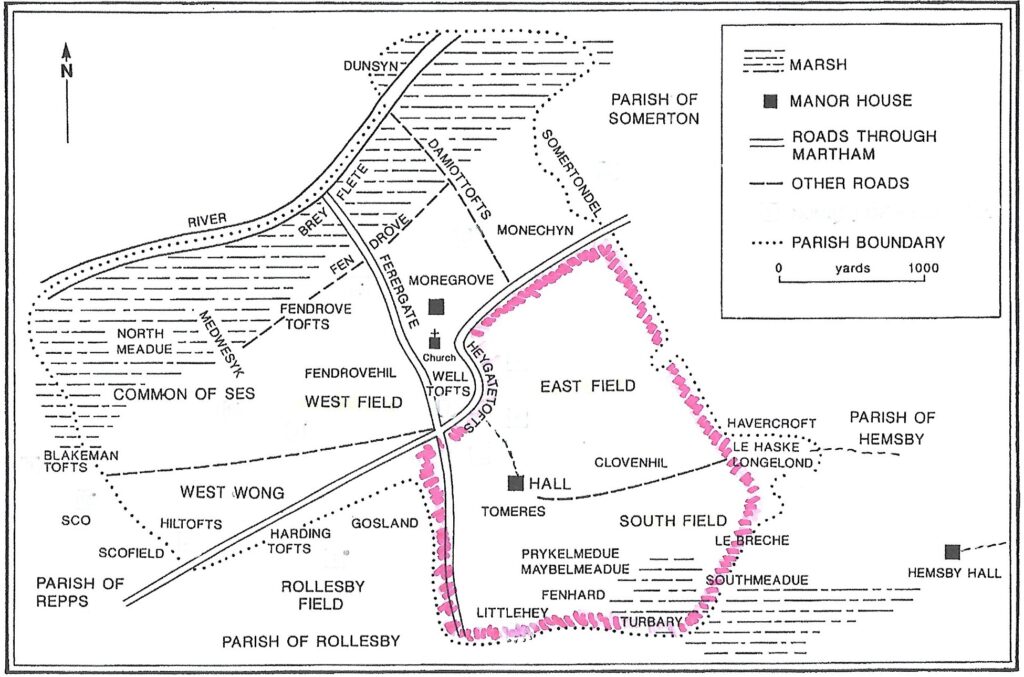

The Manor covered roughly the area shown in red on the map below which included the east and south fields and turbary north of Rollesby Broad. In addition, it had about 50 acres of meadow/marsh near the River Thurne.

Based on a map provided by Barbara Cornford and her book “Medieval Flegg”

Martham Manor flourished under these arrangements for a long while but produce prices began to rise which meant the leaseholder(s) gained and the Priory lost out because rents had been fixed. Later the Manors at both Martham and Hemsby were held on a lease by Sir Walter de Mautby but in 1257 the Priory ended the arrangement as it made sense for the Priory to manage the estate themselves and take the profits. Sir Walter was compensated by being given the manor of Beckham in North Norfolk and was paid the very large sum of £126 6s 8d for renouncing his claim to Hemsby and Martham Manors.

The Martham and Hemsby Manors were the most valuable corn producing manors owned by the Priory and it appointed a bailiff to run the estates. Arable land was valued at 3/- (15p) per acre, which was twice as much as any other land owned by the Priory and these figures explain why the Priory was so willing to pay such a high price to end Sir Walter’s lease. These prices were achieved because of the high productivity of the fertile, well-drained soil and in the case of Martham, a compact demesne laying close to the manor farmyard. It is likely that around this period the first farmhouse had been established at Hall Road although the Priory held manors in almost all the Flegg villages and the local bailiff may have lived at Hemsby which was the most productive manor and had a huge tithe barn.

The population was growing which provided a ready supply of cheap labour for the annual tasks of digging, spreading dung for compost, breaking new ground, hoeing, weeding and harvesting. The usual wage for this work was 1d or 11/2d per day. Livestock had an important function for ploughing and fertilising the fields. About three quarters of the estate was put to crop each year and the land that was left fallow was ploughed four or five times during the year to control the weeds. Peas were grown to improve the soil and provide livestock with food which, in turn, would produce dung for fertilisation. The Martham Manor also supplied the monastery with eels, pike, geese, swans and peacocks. Between 1300 & 1306 Martham kept peacocks but in 1306 one died and the remaining seven were sent to the Priory.

13th Century

Martham is unique in that it has three document sources giving details about the village in the 13th century. The first is the Account Rolls of the Manor that survive from 1261 to 1340; the second is surviving Manor Court Rolls from the 1280’s and 1290’s and thirdly a document called the Stowe Survey of 1292. Together they provide a detailed picture of the history of the Manor, its administration by the Bailiff/Steward, and the way in which the problems of the 13th century were handled.

STOWE 1292

Among the Surveys of the Manors of the Prior of Norwich contained in the volume known as Stowe Survey (MS. 936 in the British Museum) is one which has features of unique interest. It is the Survey of the Manor of Martham. The whole compilation, unfortunately, is in a defective condition. The series was apparently started soon after the appointment of William de Kyrkeby to the Priory in 1272, and was continued at various dates, the survey of Martham being made by the Prior of Norwich, Henry de Lakenham in 1292.

The key figure in the management of Martham Manor was the steward or bailiff appointed by the Priory. Twentynine annual Accounts survive from between 1261 to 1340. The bailiff’s task was a demanding one. At Martham he had to run a 600 acre mixed produce farm and maintain the Manor house and all the farm buildings including a malt kiln as well as managing a diverse and sometimes reluctant labour force and producing a detailed set of accounts. As mentioned earlier many bailiffs also had to manage more than one manor and Adam de Bawdeswell managed both the Martham and Hemsby Manors for 26 years from 1287 to 1313. He would have received some training from the steward of the monastery to ensure the accounts were kept in the manner required by the Priory. The bailiff had two officials to help him, the keeper of the grange and the beadle. At Martham the keeper of the grange was responsible for accounting for the corn at harvest time, storing it and disposing of it during the year. His account records fed into the bailiff estate accounts. He was paid 101/2d per week at Martham but was not a local man so may have worked on more than one manor. The beadle was an officer of the Manor Court who delivered summons to people ordering them to attend court and he collected fines. He was normally appointed from one of the tenants and did not receive any wages but may have been excused his manorial duties.

The Martham accounts for the year from Michaelmas 1294 to Michaelmas 1295 illustrate a typical year. In Norfolk Michaelmas was celebrated on 11th October representing the end of the old farming year, after harvest, and the start of a new one. Thomas de Eton was the keeper of the grange and had overseen storage of the grain by the end of September. It was stored in sacks by a measure called a coombe which was four bushels. Two coomb sacks equalled a quarter which was the measure corn was always sold in. A quarter of barley was reckoned to weigh about four cwt. In 1295 the sale of peas raised £7 6s 2d and sale of barley £6 9s 11d. It was sold quarterly and the Bailiff could hold some back each quarter if in his judgement the price would be better by holding on. The accounts show that 1294/95 was a better year than 1293/94. The late thirteenth century saw a succession of poor harvests but shortages meant prices increased. The Bailiff was responsible for obtaining best prices and maximum income for the Priory.

Barley was sown on about 100 acres each year at Martham whilst wheat was grown on 20 acres, peas 30 and oats 10. Half the barley crop was malted on the farm and then sent to the Priory. Barley was the universal grain used for both bread and beer. Barley bread was the general food at the manor house and formed the major part of the wages for serf labourers. It was also fed to horses, pigs, dogs, geese and hens.

On average Martham Manor sent about 18 tons of both wheat and malt to the Priory each year to be used in the kitchens and brew-houses. Surplus livestock and grain were sold locally and cash payments were made to the monastery of an average of £14 per annum in the late 13th century.

The Manor had a herd of cattle consisting of two bulls, fifteen cows, eleven bullocks and some younger stock. As well as providing milk they also provided valuable dung. In most years some of the animals were sold, usually one cow, one or two bullocks and around twelve calves. Each year new stock was added to replenish the herd and assist reproduction. Livestock was only slaughtered for food at harvest time. The bulk of milk was turned into cheese and sold at local markets. In the summer of 1295 forty-two cheeses were sold at 21/4d each.

In the mid 13th century the Priory had a flock of sheep which were normally kept on a marsh near Great Yarmouth but they were brought to Martham to have lambs and feed on the stubble for a couple of months after harvest.

The farmyard had the usual range of domestic animals including pigs, geese, doves, peacocks and poultry. Goslings were raised. Hens and eggs were also sold. The Manor also kept a small number of breeding swans looked after by a man called Simon Long who earnt 8/- (40 new pence) per year and occasionally one or two were sent to the Priory, so the monks ate rather well.

Before 1272 the Manor kept a stock of over 1,000 eels and employed a fisherman. The eel set was almost certainly on or next to the River Thurne but after an outbreak of disease in 1272/73 numbers declined and no more eels were recorded thereafter although the Manor did have two fisheries on the river.

By this time there was a Manor House at Martham where Courts were held and proceedings recorded in the Manor Court Rolls. The Lord of the Manor as represented by the Priory Steward held sway over just about everything people did not only on the Manor but for the whole of the village. Manor Courts were held about four times a year usually in February, May, June and November. A good deal of time was taken up with cases of assault, bad debts and disputes over land. Permission was required and fees were payable for just about everything, including permission to graze sheep (called right of faldage); permission to marry (merchet), permission to leave the village (chevage); permission to live in the village; permission to build a house or sell or transfer land; fines if cattle strayed; payments to be relieved of some unpopular tasks; fines for acting unsocially and even the equivalent of death duties (heriot) which were sometimes payments in kind like a lamb or cow.

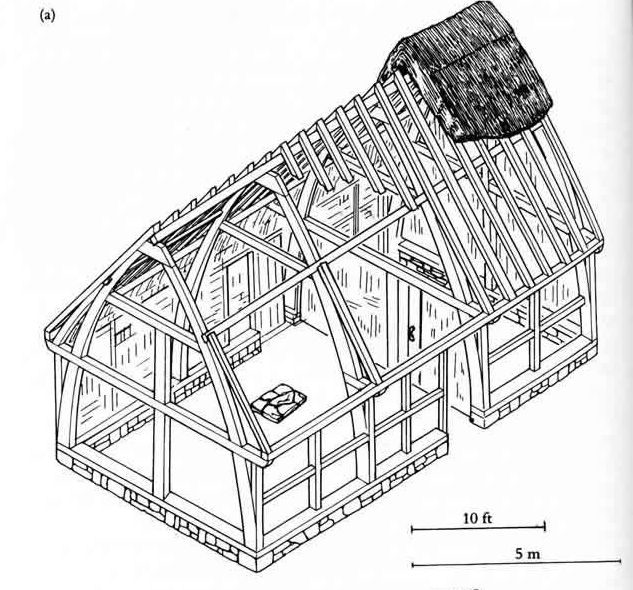

The bailiff lived at the Manor House and was responsible for its maintenance. It had a main hall where the Courts were held, two small general chambers (rooms) and separate rooms for the bailiff’s family which may have been upstairs or in another building. It would certainly have been the biggest house in the village compared with those that most people lived in which were one or two roomed wattle and daub thatched cottages but it was not grand in the manorial sense. It was probably designed based on the sketch shown above which is an example from the period. In addition to the house there were barns for storage, a malting building, dairy and other outhouses.

The Manor provided work for many people. Six labourers, a dairymaid and a cow keeper were employed throughout the year. Their combined pay in the mid thirteenth century was only 5s 4d per year but they were provided with barley every 10 or 12 weeks and were paid extra at harvest time which was the busiest time of the year. As an example, in 1296 harvest started a little late on 12th August and lasted five weeks. There were nineteen workers who ‘were resident at the Lord’s table’ for the whole of the harvest. They were Thomas Eton, the keeper of the grange, Nicholas, the beadle, six carters, three stackers, three reapers, the cowherder, the swine herder, the goose herder, the dairymaid and her helper. Workers employed for the whole harvest were paid a special rate and in 1296 the total wage bill came to £1 12s 7d and it seemed to be based on a fixed sum for each person to bring in the harvest however long it took. The Manor provided a harvest meal each day for the regular workers and for the tenants working on the demesne so on average the Manor was providing about 50 meals a day. Bread was made out of wheat and mixed corn or rye, wheat chaff and barley. Beer was brewed from malt. The Manor slaughtered a cow, provided four hams, eight geese, ten chickens, forty-five cheeses and milk from the dairy. One hundred and two mullet were bought for Friday fish meals which cost £1 2s 8d. Meals were probably taken in the hall or a barn and cooking would have been outdoors.

Outside of harvest time extra people were employed at some times of the year. Ploughmen were employed in the winter months and a swine herder and goose herder in the summer when the livestock were taken from the farmyard and fields to the meadows and marshes. Specialist tradesmen were also employed such as a smith, ratcatcher, daubers, carpenters, roofers and thatchers for the Manor House, barns and outbuildings.

All told the farm thrived during the 13th century with animal numbers constant and crop yields high for most years although there were big variations caused by the weather.

The 13th century saw considerable changes in land ownership giving rise to diversification that affected labour on the Manor. The first section of the Stowe Survey identified that the 36 original tenants in Domesday had increased to 107 in 1192 as a result of inheritance and split land holdings. It was normal in those times for land to be split equally between male members of a man’s family when he died so unless he only had one male heir the plots were continually getting smaller. By 1292 the 107 units were held in more than 900 names and the number of furlong strips held had become more than 2,000. Consequently, the average size of a peasant holding had been reduced from eight acres to just under three. It was not possible to sustain a living from such a small amount of land and by 1292 seventy-five families had two or more members who were also tenants of land on the Manor. In addition, there was a large growth in population generally and good growing conditions attracted people into the village. These people were freeholders who had a rudimentary cottage on their land and we may think of as being much better off than peasants working on the Manor but in fact they needed more land in order to survive and often became tenants of land held on the demesne. An example of one such tenant is recorded in the Manor Account Records who was Roger Hil who had a small holding at Cess called Hiltofts that is shown on the above map but in addition he had a tenancy on the Manor for which he paid 4/- (20 pence) a year in rent and 11d (about 5 pence) in aid which was an extra occasional charge levied by the Priory on special occasions as a device to supplement the fixed rent to bring the Lord’s remuneration in line with inflation. Roger had to work for three days at harvest for which he was provided with a harvest meal. He also had to carry barley or malt to Norwich or pay 11/2d fine to avoid the carrying duty. If he had a cart, he had to do a day’s carting; if he had no cart he had to come with his pitchfork. He had to thresh corn for half a day and had to make a fixed amount of malt. He had to plough if he had a plough including use of his own beasts. He had to harrow for a day with a horse or if he had no horse pay 1d. Finally, he had to give the Lord a hen and five eggs. He had to do this for holding 10 acres and any tenant who held less would have to do services in proportion to the size of his holding.

Other tenants had holdings that were too small to provide for their families’ needs but were from a growing section of society whose needs were different. The growth in population meant they had paid employment as craftsmen although the work may be poorly paid or casual. For the craftsmen of the village an acre or two of land would supplement the income they gained from being something like a carpenter, cooper, tailor, shoemaker, blacksmith or weaver. The average size of these tenants’ holdings was 1¼ acres. Their obligation to the Lord would be correspondingly smaller.

14th Century

The Account Rolls for Martham usually appeared under the names of the two manorial officers. In 1334/35 these were Peter Ockle, the keeper of the grange and Roger Orger, the beadle/collector. The accounts were written by a monastic scribe from the Priory who probably visited the Manor several times a year to collect the information. The accounts were presented in the same format for all the manors owned by the Priory showing first the income from the estate, then the expenditure and lastly the small outgoings on things like shovels, forks and equipment as well as miscellaneous labour like castration of pigs, spreading dung and transport costs, the largest of which was delivery of peat to the monastery in Norwich.

The Account Rolls for the early part of the century tell us that the Manor owned a windmill and such was the growth in demand for milling corn that from 1312 until at least 1340 it had two post mills. We do not know where they were but in 1429 a new mill was built near Le Ask or Haske on the Hemsby boundary which may, or may not, have been a replacement for an earlier mill. The present-day footpath running from Thunderhill to Somerton Road is still called Mill Lane.

The early 14th century were times of high prices and unsettled weather. In particular there were two wet seasons in 1315 and 1316 resulting in poor harvests and soaring prices. The price of wheat doubled and barley was much the same. Barley was the peasants staple food which most of time cost 3/- to 4/- per quarter but in 1316 rose to 24/- per quarter. Peasants simply could not afford those prices and starvation was common. 1315 and 1316 were sometimes called the years of the Great Famine. After a good harvest in 1319 prices dropped back to 3/- a quarter in Martham. The poor harvest did not really affect the Manor; yields may have been poor but high prices meant as much, if not more, money came in. In 1319 a cattle plague called rinderpest struck and over half the oxen and a third of the cows on the Manor died. The disease struck again in 1323/24 and 1325/26 but was not so severe. It was not until 1333/34 that the cattle stock returned to normal levels. Weather fluctuations continued and in 1325 a great drought made it difficult for the Martham Manorial cattle to find pasture. Another drought in 1335 meant no rent came in from the manorial fishery.

Medieval charity was haphazard but the records show that aid or assistance by distribution of food or money by the Prior was more frequent during the years of famine. Famine and disease were a constant problem in the first half of the thirteen hundreds but much worse was to come. In 1349 the Black Death arrived in Norfolk.

At this point you may want to read the separate page on the Black Death and how it affected Martham. The odd thing is that this event, that devastated the general population, is not reflected in the Martham Manorial accounts. The Martham documents remained beautifully written giving no sense of any stress or turmoil at a time when many other manors failed to record anything because most of the priests and scribes had died. At Martham the 1349 harvest brought in less than half the usual amount of cereal and extra men also had to be employed to thrash the corn and the harvest took a hundred and one days to bring in. The high death rate meant that many tenants holdings reverted to the Lord because they died and there was no-one to replace them so that land remained unploughed. No rushes or peat were sold. There was no shepherd and no corn was sent to the Priory yet the Bailiff tried to run the estate as usual. Extra was spent on labour from outside the demesne farm. One irony was that a high profit was made from the Manor Court on account of death duties (heriots) although more than normal had to be written-off as unrecoverable.

The 1350 harvest was long, lasting over seven weeks, and only just over half the normal services were worked because many of the tenants had died. The main problem for the estate was still the shortage of labour and extra men were employed during the spring of 1350. One man was paid £1 and the others 10/- which was quite an increase because of the shortage of available labour. A carpenter was employed to make beds for the workers who did not live locally and stayed at the Manor. A couple were employed to make meals for the workers from February to May the time for ploughing and sowing of spring corn. This was not the time of year workers would normally be fed which was only at harvest time. Twenty-eight men were paid 4/- each for the 1350 harvest which would normally have been 2/6d. There are then no Bailiff Accounts until 1355 but it is not clear if they have been lost or if no-one survived who could write and record them.

The Manor gained from death where there were no heirs. Between 1350 and 1357 only fifteen out of forty-seven deaths resulted in direct surviving heirs. Where no extended heirs were identified the land was taken into the Lord’s Manor.

Shortage of labour contributed to the rise in social problems resulting in the Manorial Court being busier than normal. Some tenants left the manor because wages were higher elsewhere and there seemed to be little attempt at enforcing fines for leaving without permission. Assaults became more frequent. In 1353 four tenants were excused fines because of poverty.

It was Priory policy to bring as much land as possible under cultivation no matter the cost but the effort to restore productivity was not immediately successful and the accounts for 1355 give the impression of a poor run-down farm.

The accounts for 1359/60 again show problems. The harvest was spoilt by heavy rain and the reduced yield of corn was sold producing £49 8s 8d of which £37 6s 8d went in payment to the Priory. The sale of so much corn led to a shortage of seed corn for the following year. The livestock was depleted with only three horses remaining and there is no record of any cows. It was not until 1363/64 that the accounts seem to show the farm had returned to its previous standards.

It is almost impossible to comprehend the suffering and misery of communities that lost up to half their population. Both peasant farms and manorial estates suffered neglect through lack of manpower and the village must have presented a dismal picture. Yet Martham survived and by the 1360’s and 1370’s economic activity had recovered.

However, in the third quarter of the 13th century, problems remained for the Bailiff. The price of corn which was the main income earner for the Manor dropped back to its pre-plague levels but wages remained high because of the lasting effects of labour shortages. These are a few examples: The annual bill for permanent labourers on the demesne increased three-fold from 8/4d to £1 11s in 1378. The total cost of labour at harvest time increased from about £2 to £6 in 1370. Craftsmen were paid 5d a day instead of the pre-plague rates of 2d a day. Friction between the Lord and tenants increased with many failing to attend their harvest manorial obligations and also ignoring subsequent fines. People found they could earn more by going the Yarmouth and working in the fishing industry even if they paid the (chevage) Manorial Court fines when they returned. The plague had seen considerable amounts of land reverting to the lord when bondmen died. Lords had spare land they were willing to sell or let but there were less takers and prices fell. In 1377/78 at Martham it was possible to rent an acre of land on a five-year lease for just four bushel of barley a year and 27 such leases were recorded that year most for an acre or two but the land totalled 36 acres. The attraction of the low prices also gave rise to a new type of tenant and the accounts show a number of the tenants of one or two acres came from other villages like Rollesby, Hemsby and Repps where they had a home probably on a few more acres. These were known as bondmen as they only had light manorial obligations in proportion to the amount of land they held rather than on their personal circumstances.

The complications caused by the Black Death, weather and shortage of labour caused considerable problems with getting people to complete the traditional manorial obligations to the Lord and collection of fines was less and less effective. Towards the end of the 14th century the Prior recognised these problems and the old rents system was changed in favour of a simpler system. Rents were fixed at 12d an acre per year with one harvest duty for every eight acres held. The Priory had started to favour money payments rather than having to receive a squealing pig or gaggle of geese delivered to its doorstep. The new rent of 12d and acre was a high price for the tenants to pay but brought the Monastery £47 10s a year indicating that just under 400 acres was tenanted on the Manor.

15th Century

In many ways the fifteenth century was a time of economic and social depression. Spasmodic attacks of the plague and other diseases kept the population stagnant. Foreign wars meant increased taxation. Great Yarmouth, which had been the wealthiest town in the Kingdom in the 14th century fell to 20th position which even affected trade in the Fleggs.

The new arrangements for renting land were easier for the Bailiff to administer and he continued to run the estate much as before. Prices were fairy steady at the beginning of the century. The number of plough horses were maintained but the number of pigs, geese and swans had declined. Income from the marsh grazing had increased and a new fishery the Priory had obtained was let for £5 6s per year ironically to the second Manor of Martham at Moregrove whose land it adjoined. Nevertheless, the Bailiff had his problems and in the first 25 years of the 15th century he had to handle continued rises in both regular wages and harvest gathering costs which meant balancing labour costs with cutting back on the number of workers. There was bad weather and rising water levels which saw some pasture flooded which could not be let. It was often difficult to collect rents and Manor Court fines. Some debts were over six years old and were never likely to be collected. All these problems resulted in a steady decline in income for the Priory and it appeared to have become more and more difficult to manage.

In 1425 there was a major change to the way the Manor was managed. The Priory leased the whole demesne to a farmer. The farmer was Thomas Drake, the previous Bailiff, who took a five-year lease on a total of 361 acres of demesne land at an annual rent of 177 quarters of barley which was approximately four bushels of barley per acre. As lessee Thomas was expected to pay the wage bill but continued to act as bailiff for which he was paid £1 6s 8d per year. The Prior continued to receive the fines imposed by the Manor Court, the barley from Thomas and rents from other land outside of that let to Thomas. For many years the Priory also retained responsibility for certain manorial managements; it provided the farmer with seven ploughs and horses and 22 cows and was responsible for maintenance of the Manor House and farm buildings including the mill all of which could be quite a financial burden. In 1428 the properties and revenues of the Priory’s Manor were valued at £21 18s 11d.

In 1429 when Thomas’ lease expired it was renewed for another five years on much the same terms. In granting only short leases the Priory Steward was probably hoping the economic climate would change and he could take the Manor back under direct management and run it profitably again which meant it was prudent to maintain the buildings in good order. However, the Priory never took the management back. The Prior, as Lord of the Manor, continued to control the Manor Court and in this way began, in many ways, to act as a magistrate.

It may seem odd that Thomas Drake could turn a profit from the estate when the Priory could not. Whilst the Priory had a large establishment in Norwich to feed, extensive buildings to keep and a prestigious position in society to maintain, Thomas would have only a modest personal household who he could probably rely on for help when needed. He also led a comparatively simple lifestyle. Having said this he appears to have prospered. In 1416 he bought a cottage and nine acres of land for £2 10s. He continued to buy land and had a holding of 30 acres at his death in 1435 having become a true yeoman.

Those tenants that rented land on the demesne outside of the arrangements for Thomas Drake fell into three categories.

Firstly, workers who were little more than the original serfs and owed allegiance to their Lord working for very little wages and were effectively owned by the Lord. They probably lived on the demesne.

Secondly, freemen who lived in the village and owned between two and twelve acres of their own land which probably had a small pightle (single roomed cottage) on it where they may also have had room to keep chickens and/or a pig. They were free to grow what they liked and sell, exchange or leave the land how they wished when they died. They may have owned a cow which was walked to the common and back daily but would have struggled to make a living from such a small holding and so rented land from the Prior’s Manor which as we have seen in the case of Roger Hil gave rise to Manorial service obligations on account of the land he rented as opposed to his personal freeholder status. Later a similar category of person grew up who were craftsman as mentioned above.

Thirdly, bondmen who were similar but were from neighbouring villages and rented perhaps only one or two acres of land on the demesne.

Almost all tenants, no matter what their status, were held responsible for the service and charges attached to the land they held but this steadily become money payments rather than service. The land they held was listed in the Manor Court records and the tenant was said to hold his land ‘by copy of the court roll’. Hence the term copyhold came about. All copyhold tenants were expected to attend the Manor Court and to abide by its regulations.

The 1497 rental record shows that most tenants at Martham held under ten acres.

16th Century onwards

From the 16th century onwards, copyhold was gradually converted, either into leasehold (by agreement between the Lord of the Manor and the tenant), or into freehold by a ‘deed of enfranchisement’. It was not until 1926 that all copyhold land became freehold.

Ironically less manorial records survive for the 16th century than the previous 500 years and so we have to retreat to snippets of information from a variety of other sources. This page was written during the Covid shutdown and more information may become available when the Norfolk Records Office opens again and further research can be carried out.

The health and living conditions of countryfolk were improving during the 16th century. Travel was easier and the population was becoming more mobile. Improvements in communication led to the spread of news and fresh ideas. Religious freedoms were expanding. Arable farming flourished providing barley for both home and overseas markets and sheep farming increased to provide wool rather than meat although there is no indication of changes in sheep rearing at Martham unlike on the Clere estates at Ormesby and Caister. Horses were replacing bullocks for ploughing at Martham and the mill was much busier. The turbaries were flooding more and more and combined with increased labour costs the result was a fall in peat cutting and income from it.

At the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536-1541) the Priory Manor became Crown property and remained so until King Edward VI was crowned in 1547. Blomefield says that between 1558 & 1602, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, Martham was held by the Crown and valued at £48. 16s. 8d. (1)

The Hobarts of Blickling Era (1602 to 1683)

In 1602 Sir Henry Hobart the 1st Baronet of Blickling (1560-1625) acquired the Martham and Somerton Estates by Royal grant from Sir Edward Clere’s estate for which he paid £177 6s 8d. Sir Henry was particularly respected for his knowledge and sophistication in matters of estate management and he seems to have been aware of the quality of the soil and consequently the yields at the Martham Manor in comparison with those to the west of the county.

When Sir Henry died in 1625 his son, Sir John Hobart, the 2nd Baronet of Blickling (1593-1647), inherited his estate and with it the Martham Manor. Sir Henry was married twice and had five sons and two daughters but only one daughter survived him and so when he died in 1647 the Blickling Estate (and Martham Manor) passed to his nephew Sir John Hobart the 3rd Baronet of Blickling (1628-1683). Accounts presented by Christopher and Robert Dey show that in 1665/66 Sir John still owned the Manor and it is believed that he remained Lord of the Manor until his death in 1683.

None of the Hobarts ever lived at Martham but it is possible that Sir Henry visited as he took a personal interest in agricultural cultivation.

The Burraway Era (c1683 to 1741)

The Burraway family of Repps were the next set of owners of the Manor but it is not known when they took over from Sir John Hobart of Blickling. The period is clouded in mystery, conjecture and lost records. The well known Martham story concerning the personal relationships that Christopher Burraway (1672-1730) had are inter-connected with the Estate. You can read his story by clicking HERE. The story stretches the truth quite a bit but has elements of fact. If it is to be believed, then his wife/mother was the owner of the Estate and before they were married he was her steward. Thus, when they married in 1702 he became Lord of the Manor.

His successor is believed to be another Christopher Burraway (1684-1741) based on an entry in the Martham Poll Book of 1734 that a Christopher Burraway “Of Repps” was qualified to vote in Martham on account of being the owner of the Manor. This Christopher Burraway was married to Mary Sutfield who came from another well-connected Martham family but his relationship with Christopher Burraway of 1672 to 1730 is unknown. It is assumed he remained as the Lord of the Manor until he died in 1741 when the house and land were bought by Phillip Proctor.

The Proctor Era (c1741 to 1781)

The Proctor family originally came from Wymondham and Norwich. Phillip Proctor (1704-1778) was the son of Francis Proctor & Ann, nee Cullyer who moved to Martham at around the time Phillip was born in the village. The Martham Poll Book of 1768 lists Phillip Proctor as being of Rollesby but qualified to vote at Martham on account of being a property owner (of The Hall) although John Preston actually lived there and was probably the Manor Estate manager.

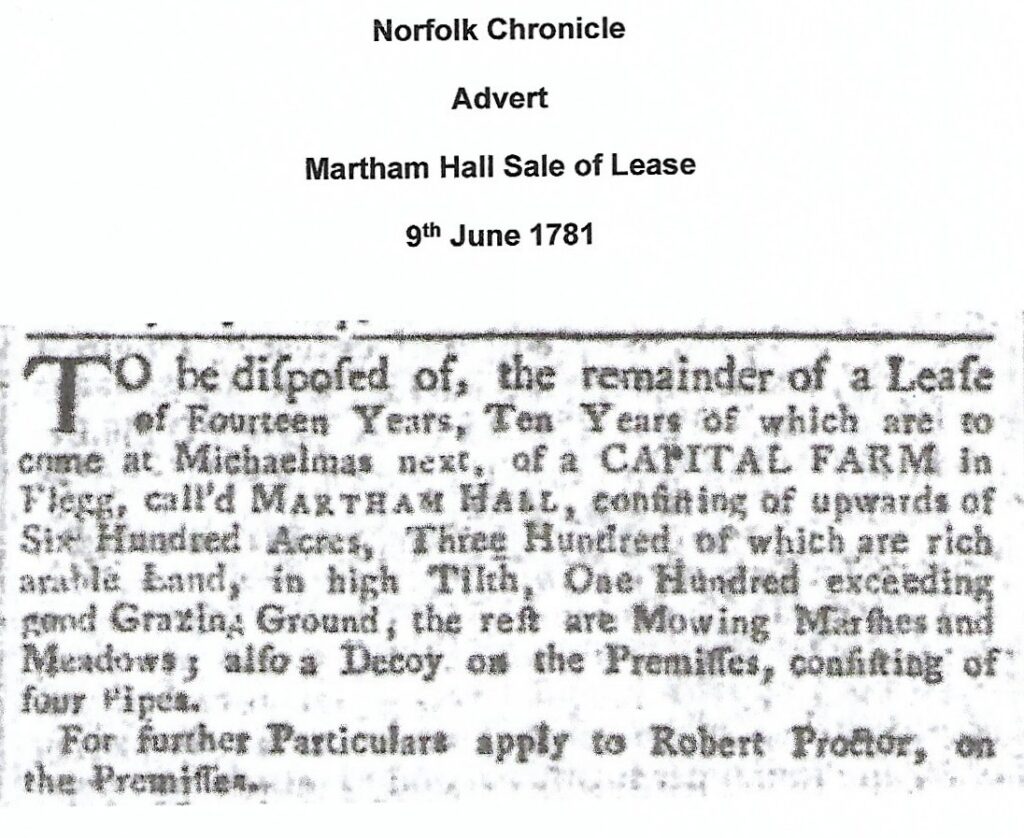

The Hall in Hall Road that stands today is a Listed Building dating to the late 18th century with early 19th century features. It may incorporate earlier features but the listing does not mention interior features. It is believed to have been built at the time of the Proctors after a previous house caught fire. There were certainly early houses on this site or just to the south of the present house in what is now the garden. The listing says it is now of brick with a pantile roof. It has a frontage of four windows and a Doric entrance right of centre with a hood. There is an ornamental block design under the cornice. It has two internal chimney stacks and there is a stair turret to the rear under a lean-to roof. Local historians say that the house attached to the right of the building shown in the above photo was built by Phillip Proctor for his son Robert. Robert Proctor (1734-1806), the son of Phillip, was recorded as living at the property. Phillip Proctor was the Lord of the Manor from 1741 until he died in 1778 when his son, Robert, took over. The lease of Martham Hall Estate was put up for sale by Robert by auction on 9th June 1781 and was advertised in the Norfolk Chronicle as having soil in especially good condition.

The Grove Family Era (1781 to 1870)

The buyer of the Manor in 1781 was Thomas Grove Esq. (1758 – 1847) of Ferne House, Donhead St Andrew, Wiltshire. The Grove family had been landed gentry for many generations and lived in a magnificent stately home in Wiltshire so the purchase of the Martham Estate was merely an investment and neither Thomas, or his successors, ever lived in Martham despite becoming Lords of the Manor.

Thomas was listed in the 1798 Land Tax records as being liable for paying £126.00 in tax for the Martham Estate. At the time The Hall was occupied by Benjamin Bowgin (or Bowgen) who was his estate manager.

Thomas was also listed in Whites Trade Directories of 1836 1845 & 1846 and Kelly’s in 1846 as Lord of the Manor and that he held a court at Michaelmas. He also appeared in the 1840 to 1846 Poll Books as entitled to vote at Martham on account of being the freehold owner of Hall Farm but his address was given as Ferne, Wiltshire.

As the owner of Martham Manor, Thomas was listed in the 1812 Inclosure Award as the owner of the estate of 410 cultivated acres plus 30 acres of decoy water and 10 acres of waste land, two barns, two stables, a granary and a house and garden. Benjamin Bowgin was his bailiff/manager and lived in the farmhouse and his land agent was Samuel Bell. The land he owned was mostly in the south fields area stretching down to Rollesby Broad as shown in red on the map below with the farmhouse area in green. This is much the same area cover by the 13th century Manor, and you can see why it was described then as a compact demesne. In addition, he also owned some marsh/meadows near the River Thurne. The 30 acres of decoy was on the edge of Rollesby Broad.

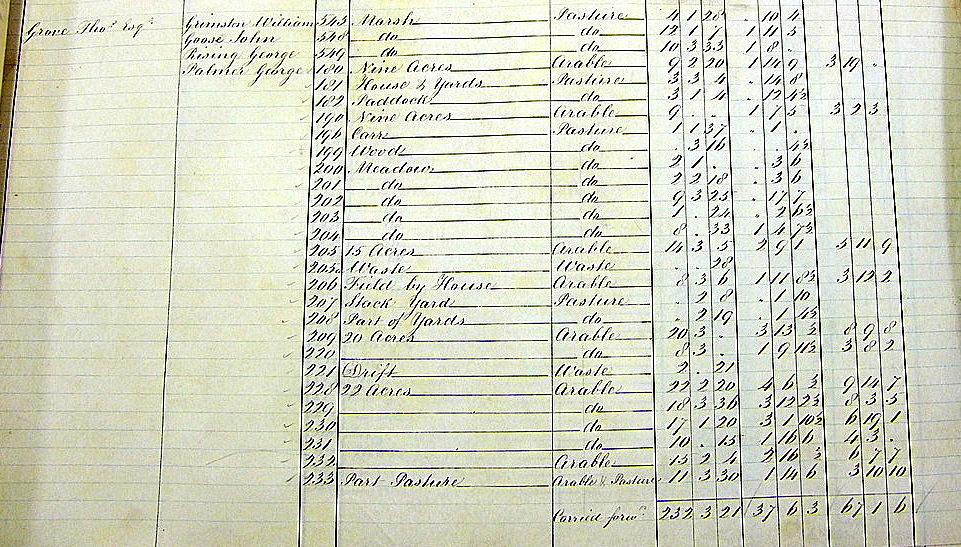

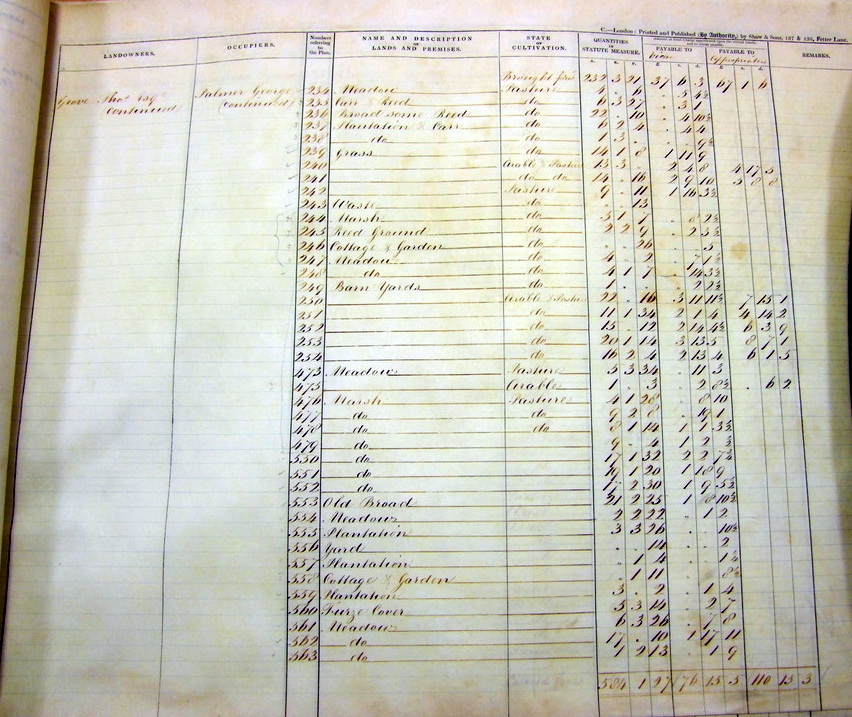

Thirty years later he was still the Lord of the Manor at the time of the 1842 Tithe Award but had increased the Manorial lands to 584 acres some of which were let to William Grimston, John Goose, George Rising and George Palmer. The copies of the Tithe Award lists shown below tells us which plots he owned and includes a description and size of each one.

The following two maps are based on the 1812 Commissioners maps from the records of the Dean & Chapter of Norwich held in the Norwich Record Office ref: CHC 11910 and BR 276/1/172 but show the land Thomas owned in 1842 outlined in red with The Hall home farm outlined in green. The land he had added since 1812 is probably plots 550 to 563 just north of The Grange and on the border with Repps. Plots 556 to 558 are where White Gates Farm is today.

Thomas died in Wiltshire on 22nd April 1847 and the Manor was inherited by his son John Grove Esq. (1784-1858). White’s business directory of 1854 listed John as being Lord of the Manor which he remained until his death in 1858.

John had a son called Thomas Frazer Grove (1823-1897) who was his heir. Thomas was born on 27th November 1823 as the son of John Grove & Jean, nee Frazer, the daughter of Sir William Frazer.

Thomas (shown left) was a captain in the 6th Dragoons and a Deputy Lieutenant and J.P. for Wiltshire. He was the High Sheriff of Wiltshire in 1863 and a Hon. Lieutenant-Colonel of the Wiltshire Yeomanry Cavalry. Thomas married Grace Catherine O’Grady, the daughter of the Hon. Waller O’Grady, Q.C, in 1847. After her death in 1879, he married Frances Hinton Barnewall, daughter of Henry Northcote and widow of the Hon. Frederick Barnewall. Thomas was made a baronet on 18th March 1874.

He was elected at the 1865 general election as Member of Parliament for South Wiltshire and was re-elected in 1868. After his defeat at the 1874 general election, he did not stand again until after the 1885 redistribution of seats. At the 1885 general election he was elected as the Liberal MP for Wilton. When the Liberal Party split in 1886 over Irish Home Rule, he joined the breakaway Liberal Unionist Party which opposed Home Rule. He was re-elected unopposed at the 1886 general election, but at the 1892 general election he lost his seat.

He was listed as being the Lord of the Manor at Martham in White’s Business Directories of 1845 and 1864; Harrolds Directory of 1868 and the Post Office Directory of 1869. He was also listed as being the Lord of the Manor in some leases of a cottage and blacksmiths he owned in Black Street in 1864(2). In addition he owned a substantial amount of land in Somerton and Winterton.

Thomas died, aged 73, on 14th January 1897 when the baronetcy passed to his son and heir Walter, but Thomas had sold the Martham Estate many years before in 1870 meaning he was Lord of the Manor from 1858 until 1870.

During the Grove ownership era the three members of the family never lived at Martham. Instead, they let the Manor farmhouse and farmland to a tenant farmer. From 1841 until at least 1861 it was occupied and farmed by the Palmer family. The 1841 census tells us that George Palmer (1811-1846) lived at The Hall with his wife, Emily, and three children. George died in 1846 and the Manor was run by his wife who was listed in the 1851 census as the head of household and a farmer of 500 acres employing 29 labourers. She was still there in 1861 farming the same land with the help of her son George and they employed 13 men and six boys. As tenants rather than freeholders they were not Lords of the Manor.

The Hewitt and Capon Era (1870 to 1882/83)

On 11th June 1870 the Manor was sold by Thomas Frazer Grove to John Hewitt (1814-1873) of Norwich, a Land Agent and Surveyor for £5,250. The sale schedule read:-“All that Manor or Lordship or reputed Manor or Lordship of Martham in the County of Norfolk with the rights, royalties, members and appurtenances thereto actually or by reputation belonging, and all and singular messuages or rights etc. And, the reversion etc., And all the Estate etc. To hold the said Manor and hereditaments with the appurtenances unto and to the use of the said John Hewitt his heirs and assigns forever.” (2)

As a land surveyor and auctioneer John did not live at Martham and like so many of the other owners was really just an absentee investor. He was born at Thrigby so he may have had an allegiance to Flegg but he lived and died in Norwich.

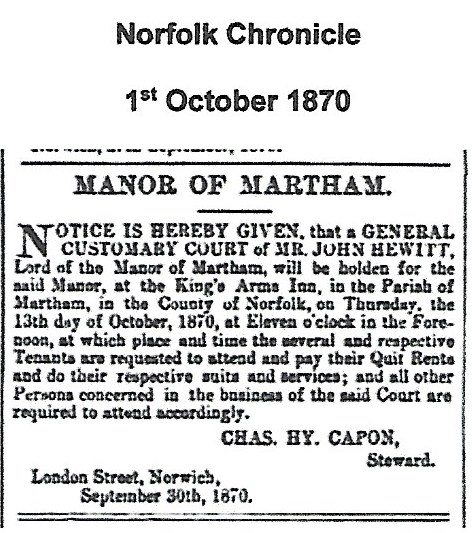

The quarterly Manor Courts held by the Prior had reduced along with his power. Once the Manor had passed into private hands the Lord ceased to have the same powers of servitude. The introduction of constables and establishment of magistrate courts virtually rendered the Lords community powers obsolete. Meetings of the Manor Court did however continue for somewhile for the collection of rents etc due from tenants. These were generally held at the traditional time of Michaelmas and below we have a copy of a notice printed in the Norfolk Chronicle on 1st October 1870 that not only proves that John Hewitt was Lord of the Manor but that his friend and business partner Charles Capon posted the announcement.

John was not the Lord of the Manor for long; on 4th November 1872 he made a Will leaving, after bequests, all his property to his friend and partner Charles Henry Capon, of Norwich. John Hewitt died on 24th January 1873 and his Will was proved on 8th February 1873(2).

So, Charles Henry Capon (1842-1885) became the Lord of the Manor in 1873 and yet again he was only an investor. He was born at Catton, Norwich and grew up to be a surveyor and auctioneer like his business partner John Hewitt. Charles was married to Sarah Ann Hastings and they had five children but they never lived at Martham.

Charles was listed in the Poll Books from 1873 to 1882 as being entitled to vote at Martham on account of being the freehold owner of Martham Manor and lands. He was also listed in Kelly’s/Harrolds Business Directories of 1877 and 1879 as Lord of the Manor of Martham. Throughout this period he lived in Norwich. He died in 1885 at Norwich.

The John Love Era (Lord from 1882/83 to 1896)

Once again, we find that neither John or Charles lived in Martham and they let the estate to tenants. In 1871 John Newman Waite was the tenant at The Hall and farmed the estate. He was 38 and had been a tenant at other farms for many years. He lived at The Hall with his wife and two daughters but left by 1877 and was shown in the 1881 census as farming at Bramerton, Norfolk.

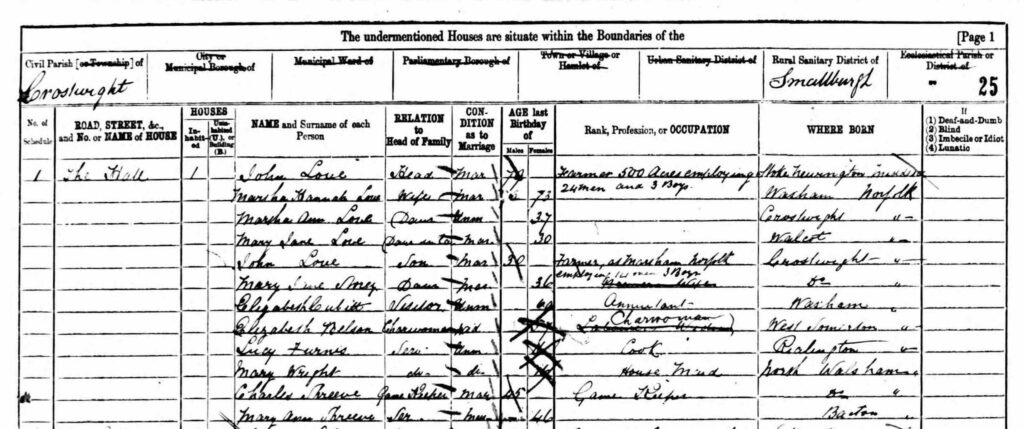

According to Kelly’s Business Directory of 1877 John Love (1850-1903) was the tenant farmer and lived at The Hall with his wife Mary. John came from a family steeped in farming and his father, of the same name, farmed over 500 acres at Crostwight, Norfolk. John began farming at Martham Manor as the tenant of Charles Capon but by 1882/83 Charles was suffering poor health and sold The Hall to John as the sitting tenant, thus John Love (b1850) became Lord of the Manor. John must have worked closely with his father and they may have combined the day-to-day running of Martham Manor and Crostwight Hall farms as one because at the time of the 1881 census John was living with his father at Crostwight but the form said he farmed at Martham employing 14 men and 3 boys.

If both John Snr. & John Jnr. were living at Crostwight in 1881 who was at The Hall? The answer is that the house was only occupied by two young ladies who worked for the Love’s and were both from Walcott which is near Crostwight. One was Caroline Webster a dairy maid and the other was Emily Payne a domestic servant.

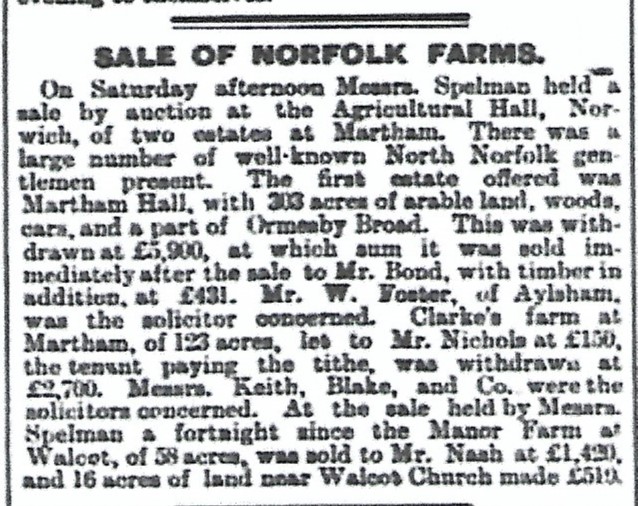

John Jnr. and his first wife Mary did live at The Hall in 1891 but by 1896 John had decided to sell the Estate and it was put up for auction on 1st August. An advert for the sale of the house, 303 acres of arable land, woods and part of Ormesby Broad appeared in the Eastern Daily Press as shown below. A week later an article appeared in the press reporting that the sale did not achieve the reserve price but was sold immediately afterwards for £5,900 to William Bracey Snr. (1847-1922) of Martham. As a result, he appeared to also have become the Lord of the Manor but according to other records this was not so.

Late 19th Century & 20th Century

You can see from the sale advert above that the size of The Hall Farm had fallen to 303 acres in 1896 down from a high of 584 acres in 1842. Successive owners had obviously steadily sold off parts of the estate. This brings us to a fundamental change to the status of the Martham Manor Estate at The Hall and the title of Lord of the Manor. Until 1896 the Estate had always been the largest in Martham and as such held sway over the parish and its owner had been recognised as Lord of the Manor for over 900 hundred years.

I can find no official record that the title of Martham Lord of the Manor exists in writing although at the time of compiling this page the National Archives and the Norfolk Records Office are in shutdown as a result of the Covid crisis. It seems to have long been established, even if unofficially, that the Lord of the Manor was the largest landowner in the village and by 1896 this link with Hall Farm was no longer the case. By this time the title was largely customary even when attached to the largest landowner and it was not enshrined in law. The former medieval powers attached to the title had been eroded or superseded by changes in land ownership legislation and law & order statute.

So, the sale notice of 1896 did not claim that Hall Farm was a manor or even the reputed manor and the title Lord of the Manor was not mentioned. Generally, a title Lord of the Manor may or may not be connected to a Manor. Hall Farm at Hall Road was no longer the Manor of Martham because it was no longer the largest estate in the parish and over 900 years of history had come to an end.

In 1890, six years before John Love sold The Hall, the largest landowner in Martham had become Mr Alfred Mabbott Wiseman (1823-1905) who had been living and farming 358 acres at The Grange in 1881 and he had become the Lord of the Manor although it was really only an honorary title by this stage. Alfred moved to Martham House in 1890 where he also held the 156 acres there. Kelly’s Business Directories of 1892, 1896 & 1904 confirm that Alfred was Lord of the Manor. He died in 1905 but even in 1908 his Trustees were noted as being the Lords of the Manor according to Kelly’s Directory as they still administered the land he had previously farmed.

The Trustees of Alfred Mabbot Wiseman eventually put Martham House Estate up for sale in July 1908 and William James Bracey Snr. (1847-1922) bought that as well. William had amassed a considerable amount of land in the village and had become an extremely successful brickmaker, dairy and fruit farmer. You can read more about him by clicking HERE. The centre of operation for William Bracey and Son was a house that had previously been called Hughenden Lodge in Back Lane opposite the pond but William had renamed it Manor Farm probably to assert the fact that his acquisitions had meant he was by far the largest landowner in the village, farming at one point 935 acres, and had become Lord of the Manor. William died in 1922 and there was a dispute about his Will which took a long time to resolve during which time his son of the same name ran the estate. His estate was finally settled in 1937 with William Bracey Jnr. purchasing Manor Farm from the Trustees and retaining the title of Lord of the Manor. William Jnr. changed the name of Manor Farm to Manor House and even though it had never been associated before with the ancient Manor of Martham it now had a title to fit its purpose.

William remained the Lord of the Manor at Manor House, Back Lane until his death in 1949. The Bracey business continued as a family trust until 1971, when Raymond Crisp, the grandson of William (Jnr.) took over both the business and the title Lord of the Manor which he retains to this day (2021).

The Hall, Hall Road after 1896

Photo courtesy of Ann Meakin.

When William James Bracey purchased The Hall in 1896 he added the farmland to his business but never lived at the house. According to the census of 1901 The Hall was occupied by Charles & Mary Shreeve. He was 66 and came from North Walsham and was the caretaker at The Hall. He had been a gamekeeper for the Love family at both Martham and Crostwight and it seems that William Bracey kept him on after he purchased the farm. Later the Shreeves moved to Bottle Hall Cottages, off Repps Road. Charles died at Martham in 1921 and Mary died in 1924.

In 1911 a career farmer called Arthur Thorton Duberly lived at The Hall. He was born at Broome in Bedfordshire in 1887. Arthur did not stay long at Martham and moved to Great Ormesby and later to North Walsham.

Sadly, the Manor of Martham does not live up to the popular picture of a medieval estate dominated by one family who built a grand house that it occupied for generations, graced with a cultivated landscape which survives to be admired even today. Instead, the Manor of Martham has been owned by a long succession of landowners most of whom probably never lived in, or even visited the village. Consequently, there has never been a stately home or even a really grand manor house associated with Martham Manor.

Summary of Lords of the Manor of Martham

1090 – 1119. In 1090 Bishop Herbert de Losinga founded the Cathedral Priory Monastery at Norwich and at the same time converted his rights of patronage over lands in Norfolk and Suffolk into those of a Lord of the Manor thus becoming the first Lord of the Manor of Martham.

1120 – c1536 Subsequent Bishops of Norwich were the Lords of the Manor until the Reformation.

c1536 – 1602 At the Dissolution of the Monasteries Martham Priory Manor became Crown property and remained so through the reigns of Edward VI and Queen Elizabeth until 1602.

1602 – 1625 Sir Henry Hobart, the 1st Baronet of Blickling.

1625- 1647 Sir John Hobart, the 2nd Baronet of Blickling.

1647- 1683 Sir John Hobart, the 3rd Baronet of Blickling.

1683 – 1702 Mary Lane (mother of Christopher Burraway (1672- 1730).

1792 – 1730 Christopher Burraway. (1672-1730)

1730 – 1741 Christopher Burraway (1684-1741).

1741 – 1778 Phillip Proctor. (1704-1778)

1778 – 1781 Robert Proctor. (1734-1806)

1781 – 1847 Thomas Grove Esq.

1847 – 1858 John Grove Esq.

1858 – 1870 Sir Thomas Frazer Grove.

1870 – 1873 John Hewitt.

1873 – 1883 Charles Henry Capon.

1883 – 1890 John Love.

1890 – 1905 Mr Alfred Mabbott Wiseman.

1905 – 1908 The Trustees of Alfred Mabbott Wiseman.

1908 – 1922 William James Bracey.

1922 – 1937 Trustees of William James Bracey.

1937 – 1947 William Bracey Jnr.

1947 – 1971 The Bracey Family Trust.

1971 – Raymond Crisp.

SOURCES:

This page could not have been written without the incredible information provided by Barbara Cornford and her book “Medieval Flegg” which is a must read for anyone interested in the history of Flegg from 1086 to 1500.

(1) British History on-line.

(2) Title Deeds in respect of 19 Black Street, Martham a copyhold property owned by Thomas Frazer Grove.

(3) From Danelaw, a freeman enjoying extensive rights over his own land.

Also, “Glimpses into the History of the Village of Martham” by Ann Meakin.