Domesday Martham

In 1066 Duke William of Normandy conquered England and became better known as William the Conqueror. As a conquering King he effectively owned all the land in England which he soon granted to his supporters and followers. In 1086 William ordered a survey of all his realm to assess the extent of the land and resources owned and thus the amount of the taxes he could raise.

Royal commissioners were sent out around England (except most of Cumberland and Westmorland which was not part of England at the time) to collect and record the information from thousands of settlements. A set of standard questions were put to a court of local representatives – made up of the Shire Court Sheriff, the local priest, reeve, landlords, freemen and six villeins from each village. The commissioners wrote down all the information in Latin, as was the final Domesday document itself. The information was collected at Winchester and was combined with earlier records, from both before and after the Conquest of 1066 and was then entered into the final Domesday Book.

The questions asked were:

- The name of the place and who held it?

- How many carucates(1) or hides(4)?

- How many ploughs(5), both those of the Lord and of the freemen(3)?

- How many freemen(3), sokemen(6), slaves/serfs(7), villeins(10), bordars(10)? There were only twelve slaves/serfs in the whole of Flegg. (The description of some of these varied in different parts of the country).

- How much land was cultivated, how much was woodland, meadow and pasture? (There was very little woodland in Flegg because the soil was very fertile and was cultivated at the expense of trees).

- How many churches, mills, saltpans and fishponds etc?

- How much had been added or taken away?

- The total annual value?

The whole purpose of the survey was to value the land and its assets and gather the same information for three periods which were: (1) before the Norman Conquest in 1066; (2) when the King granted it in 1066 and (3) at the time of Domesday in 1086. The information was extensive but was not always collected.

The number of ploughs(5) was recorded on every manor and farm and included its team of eight oxen. It was important because it was essential for cultivation. The wooden plough could be replaced fairly easily but the animals that pulled it represented several years of regular attention from breeding to nurturing. In general, the more plough-teams there were on a manor the greater was its value.

There was no woodland recorded in Martham but it did have large areas of meadowland most of which was alongside the River Thurne and was important for summer grazing and winter fodder for the oxen. Surprisingly, there was no record of peat digging or fisheries which were both known to exist. Peat was the main fuel in the village at the time but it may have been that it could be cut freely and therefore had little or no value. The same may well have applied to fisheries.

The information that was collected was collated and abridged chiefly by omission of livestock and the 1066 population. It was copied in a shorthand Latin by one writer by hand into two huge books, in the space of around a year, but was interrupted by the death of William in 1087. Volume I included all the shires except Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex which were completed later and made-up Volume II or the Little Domesday Book.

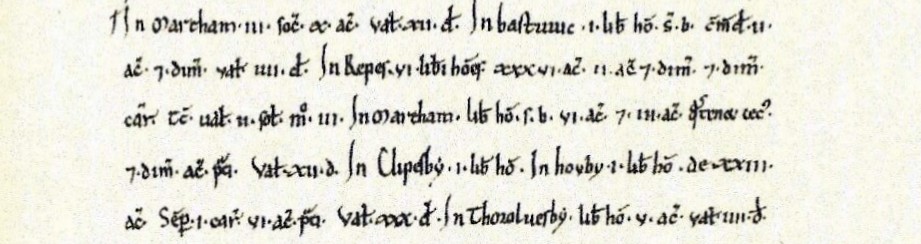

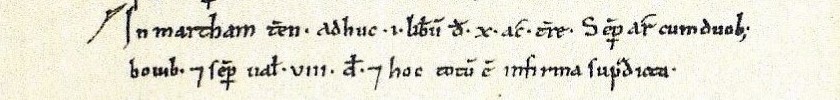

Martham was in West Flegg Hundred and the court was probably held in the open air at Stefne Heath which was just off what is now the B1152 centrally situated between Martham, Rollesby, Ashby and Clippesby at what is still called Heath Road. Despite the information being collected at a local level it was not recorded by village or settlement but under the name of each landowner because the purpose was to use it to raise taxes. Consequently, to find the details for any place, including Martham, you have to find where it has been listed under landowners. Thankfully, Domesday has now been digitalised and can also be searched by place name which shows that there were seven listings of chief landowners for Martham. These landowners were men or bodies of regional or national reputation who held estates all over East Anglia and beyond. In several cases the information is drawn from land holdings stretching across many villages and as a result the data for just Martham cannot be extracted from the whole. None of the Saxon overlords lived in Flegg or Martham and many probably never set foot there. The entries relating to Martham are shown below along with a copy of the original entry in Domesday in Latin.

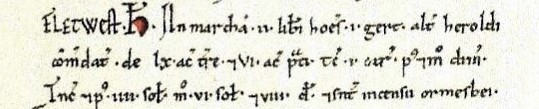

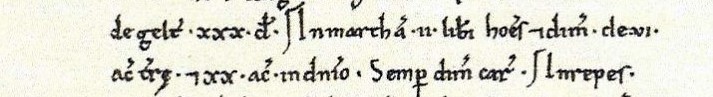

Lands of King William (William the Conqueror)

- 2 freemen.

- One plough in 1066; half a plough in 1086 (shared with other lands at Ormesby).

- 60 acres of land and 6 acres of meadow.

- Valued at four shillings before 1066; four shillings in 1066 and six shillings & seven pence in 1086.

- The two freemen overlords in 1066 were Gyrth and King Harold.

- The Tenant-in-chief in 1086 was William the Conqueror.

- The Lord in 1086 was William the Conqueror.

Gyrth was King Harold’s (1066) brother and also held the large and valuable manor of Ormesby from St Benet’s Abbey of Holme.

Lands of King William (William the Conqueror)

- 5 freemen in 1066.

- Shared three acres of meadow.

- The owners in 1066 were the five freemen.

- The Tenant-in-chief in 1086 was William the Conqueror.

- The Lord in 1086 was William the Conqueror.

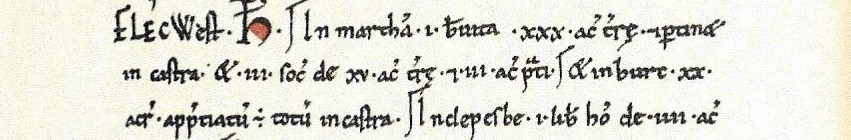

Lands of Count Alan (of Brittany)

- 2.5 freemen.

- Half a plough team (probably one shared with another area).

- 6 acres owned by the 2.5 freemen in 1066.

- 20 acres held by the Lord in 1086.

- The owners in 1066 were the freemen.

- The Tenant-in-chief in 1086 was Count Alan.

- The Lord in 1086 was Count Alan

Count Alan also held land in Bastwick and Repps under this entry so some of the above was shared, thus accounting for entries of “half”. Count Alan also had a large manor at Somerton that later became the parish of West Somerton, whilst the King’s smaller manor became East Somerton. He was a second cousin of William the Conqueror; was part of William’s household and took part in the Battle of Hastings commanding the Breton contingent.

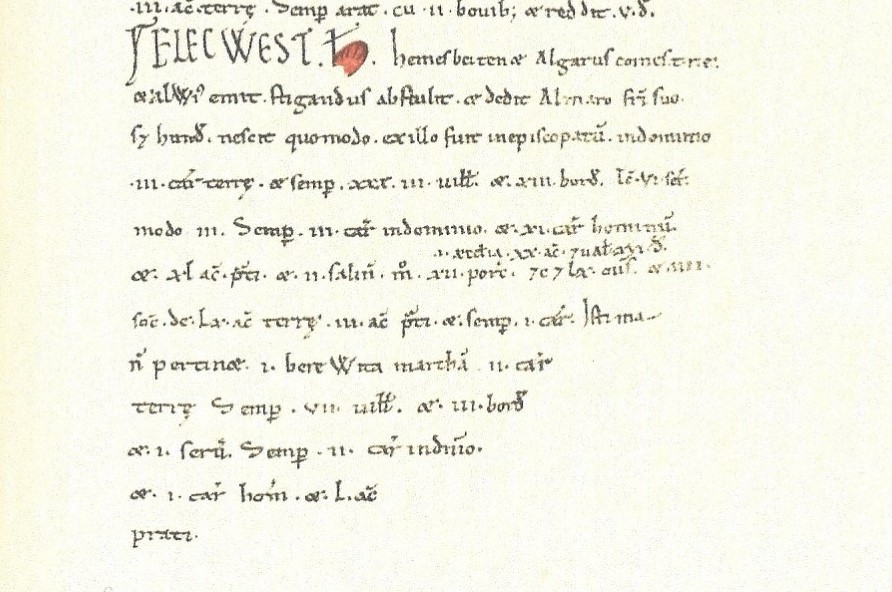

Land of Bishop William of Thetford. (Previously Earl Edgar)

This part of Martham included Sco which at the time was listed as a separate, very small, manor with one freeman and two bordars. Martham and Sco were held by Earl Edgar before 1066 as part of his larger manor of Hemsby but the Martham land was purchased by A(i)lwy. Later Archbishop Stigand took it away and gave it to his brother Bishop A(e)lmar of Elmham and by 1086 it came under Bishop William de Beaufeu (or Beaufoe) at Thetford.

- 7 freemen, 3 smallholders and one slave.

- 240 acres (2 carucates) of land plus 50 acres of meadow.

- Two ploughs owned by the Lord in 1086 and one by a freeholder.

- The annual value of the Martham element is not available. The estate as a whole was valued at £26 in 1066 and £29 1s 2d in 1086 which included lands in Hemsby, Martham, Sco and Winterton.

- The Lord in 1066 was Earl Edgar.

- The Tenant-in-Chief in 1086 was Bishop William (of Thetford).

- The Lords in 1086 were Richard (son of Alan) and Bishop William (of Thetford).

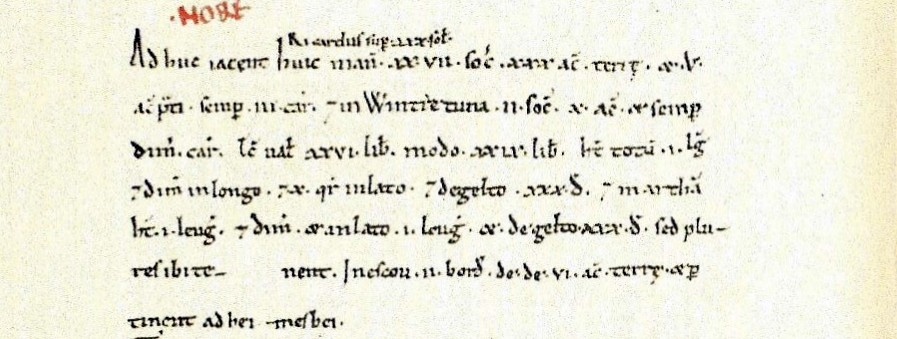

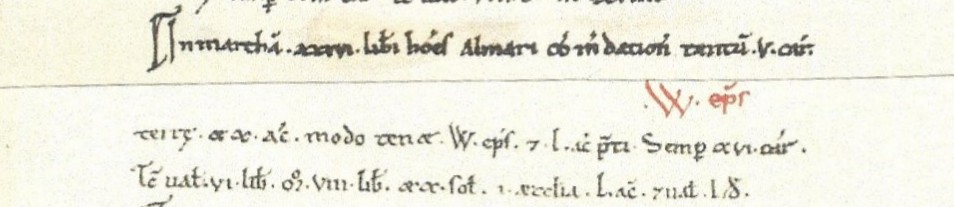

Land of Bishop William (of Thetford)

- 36 freemen.

- 16 plough teams.

- 600 acres (5 carucates) in demesne(2) plus 10 acres of meadow.

- One church with 50 acres (valued at 4 shillings & 2d in 1086).

- The demesne(2) was valued at £6 per annum in 1066; £8 10s per annum in 1086.

- The Overlord in 1066 was the Bishop Almer (the seat of Bishop Almer was at Elmham at that time).

- The Freemen in 1066 were the 36 men.

- The Tenant-in-Chief in 1086 was Bishop William de Beaufeu (the seat of the Bishop was at Thetford by 1086).

- The Lord in 1086 was Bishop William de Beaufeu (the seat of the Bishop was at Thetford by 1086).

The Bishop also held a considerable amount of land in other manors across Norfolk including at Hemsby, Sco and Winterton. The land held at Martham in 1086 was the Prior’s Manor at Hall Road with an unusually high number of freemen at 36. In addition, in 1086 there were also seven villeins(10) and three temporary bordars from elsewhere that would have worked directly on the Manor.

Land of the Abbey at St Benet of Holme

- 3 freemen owned 10 acres, a freeman of St Benet’s owned 6 acres at Martham and a blind man owned 3 acres plus half an acre of meadow.

- The 10 acres were valued at one shilling in 1086.

St Benet’s owned a great deal of land in other manors including Bastwick, Burgh St Margaret, Clippesby, Hemsby, Oby, Repps, Rollesby, Scratby and others beyond. Individual valuations and plough team use for Martham is not possible to identify. - The Overlord in 1066 was the Abbey at St Benet of Holme.

- The Lords in 1066 were one freeman and the Abbey at St Benet of Holme.

- The Tenant-in-chief in 1086 was the Abbey at St Benet of Holme.

- The owners in 1086 were the blind man and the Abbey at St Benet of Holme.

Land of Others in 1066 (King William in 1086)

- 1 freeman.

- One-third of a plough team.

- The annual value was 8d in both 1066 and 1086.

- The owner in 1066 was the one freeman.

- The Tenant-in-Chief in 1086 was William the Conqueror.

- The Lord in 1086 was William the Conqueror.

You may wish to read about other topics related to Domesday as they apply to Martham which can be found by clicking on any of the following:-

Terminology:

Carucate was equal to about 120 acres, often used in Norfolk and Suffolk instead of ‘hide’. The carucates given may not be accurate but give an idea in relative terms of the size of a manor.

Demesne was the home farm of a manor.

Freemen normally owned a small amount of land sufficient for their own needs but sometimes aligned themselves with a powerful Lord for protection in exchanged for providing minimal services like helping at harvest time. They were free to sell their land or will it upon death.

Hide was a Saxon measurement of land which converts to about 120 acres.

Plough was a word that included a team of eight oxen. It was based on being able to plough a carucate of land in a day.

Sokemen were almost always attached to a manor and may have had specific duties like ploughing. They may have rented small amounts of land from the Lord to provide for their own basic needs.

Slaves/serfs were labourers on a manor with no status and did not own any land.

Socage was a feudal tenure of land involving payment of rent or other non-military service to a Lord.

Tenants-in-chief were landowners who held their lands directly from the Crown after the Conquest in 1066.

Villeins or bordars were attached to manors and provided much of the labour force of the manor accountable to the Lord. ‘Bordars’ may have lived in another village and travelled to work on a neighbouring manor.

Sources:

My grateful thanks to:

Barbara Cornford and her book Medieval Flegg, ISBN 0 9948400 98 6.

Philippa Brown, “ Domesday Book for Norfolk”.

Permission given by Professor John Palmer, George Slater and opendomesday.org. to publish the original Latin text entries under the CC-BY-SA licence.