Black Death at Martham

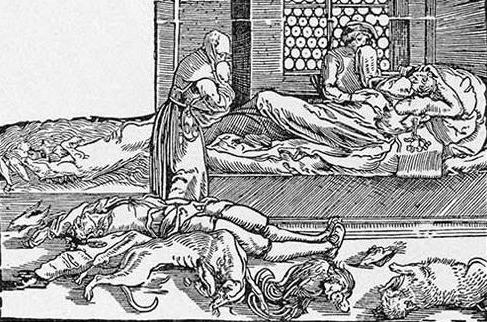

The most dramatic health event of the Middle Ages was the plague known as the Black Death which spread across Europe from the east in the late 1340’s. It is generally accepted that it first appeared on the south coast of England in the summer of 1348 and spread to London by November that year. The epidemic reached Norfolk in the spring of 1349. It was reported that no less than 7,000 out of a population of 10,000 died in Great Yarmouth, but in fact the mortality rate can only be guessed at. The Black Death did not disappear but attacked many times over the next 300 years. Later waves were less fatal than that of 1349 but contributed to a stark reduction in the population that created a labour shortage in rural locations, higher wage rate and increased cost of farm production.

Martham had a population of about 400 at Domesday in 1086 and by the time of the Stowe Survey in 1292 the population had increased to 1,000 making it a very large village. The Black Death then struck the village reducing the population by about a half. Even by 1497 there were still only 77 holders of land in the village down from 376 in 1292.

There is no contemporary account of the times for Martham but the Vicar of Rollesby, Simon de Rykenhale, wrote the following account which no doubt equally applied to Martham being a neighbouring village. He was the Vicar at Rollesby from 1349 to 1361. He says:

“I took over from the parish priest, Walter Hurry, just after the Death*, in 1349. Although we have had occasional scares it never quite returned with the ferocity of 1348. It was a dreadful time, and most especially in Rollesby and the Great Yarmouth area. By the time we reached the year of my arrival, 1349, it was claimed, with some justification, that a third of the population lay dead from this purge. Walter Hurry did the best he could….. he urged the villagers not to travel, not to mix with strangers and to keep the village as clean as possible. Sadly, one of his flock, some self-righteous fool by the name of Beech, thought the advice was silly and continued his trade at Yarmouth quay. He brought the plague back and there was no stopping the illness after that mistake. Men, women and children fell like acorns and conkers in season, and, unlike some priests, Walter buried the dead and anointed the dying. Ironically it was because of the visit he made to the Beech family he caught the illness and died within days…… he was buried by the church tower. Future readers no doubt will have their own plagues and illnesses to worry about, but I sincerely hope they never have to cope with a death like this one. The swelling of the glands and ulcerous boils that pulsate with a greeny yellow pus exude a sweet sickly smell; this is the announcement of death once it is in the nostrils.

The death of clergy in Ormesby and Rollesby and many other parishes has indicated to parishioners that the clergy at least did their jobs. I have been told that half the clergy in the Norwich Diocese died, and altogether some 800 priests in East Anglia alone.

There is a shortage of priests now, but there is a shortage of people as well. The Bishop of Norwich gained special dispensation to allow 60 clerks aged 21 years or less to hold rectories on the grounds that his action was better than nothing. On 6th April 1350 the Bishop of Norwich established Trinity College at Cambridge to make sure more clergy were trained following the appalling loses.

The people of Rollesby wailed and mourned and were terrified, but they buried their dead, moved the village away from the burial grounds of the church and life goes on.

Since the Death, labourers have been in short supply and they tend to move around the area looking for better pay. Some of our folk have gone to Martham and Filby and even further seeking better wages. Parliament passed laws against such practices but few in this area can enforce them. Managing to find good labourers has become a problem; they demand too much money and too easily move to better pastures.”

Using taxation records it is possible to guess the population of Rollesby in 1332 at about 400 to 500 of whom about half died of the Black Death. On the same basis the population of Martham was about 1,000 of which about 500 died of the illness.

The priests of Martham appear to fair no better than those in Rollesby. Martham had three priests in 1349 and although no reason for their deaths is known it was almost certainly the plague. Thomas de Halvergate had been the priest since 1342 but died in 1349; William de Wardeboys arrived and died in the same year followed by John Spyre who seems to have survived. Similarly, Ashby, Fleggburgh and Ormesby St Margaret all had three priests in 1349 and Scratby had four. A post mortem report of 1351 stated that all the tenants of the manor at Runham had died.

The manorial accounts for Martham show that the 1349 harvest brought in less than half the usual amount of corn. No rushes or peat were available and tenants could not be found for many of the marsh pastures. Unusually no corn was sent to the Priory that year that usually had first call on it. Eleven tenants were excused payments of rents and fines. Ironically the manor did gain from higher death duties although it may have been some of these that were waived.

The main problem for the manor was the shortage of labour and less than half the usual hoeing and harvesting services were performed. Wages increased and the accounts showed that a man and his wife were hired to make meals for the workers from February to May, the time for ploughing and sowing spring corn. It was very unusual for workers to be fed at the expense of the Lord of the Manor. More livestock were eaten by the manorial household and more stock sold to pay the extra wage bill.

The reduction in population gave rise to a situation where labourers had more choice of work, they became more assertive and communities experienced a greater degree of social disorder. The manor court rolls record instances of damage to the manor farmyard; increases in assaults; marriages without licences; fines for livestock not being under control; sheep and cattle straying onto open fields; neglect of communal responsibilities; failure to maintain banks and ditches and failure to turn up for harvest services. The manorial accounts for 1355 give the impression of a poor run-down farm. These problems were made worse by a succession of poor harvests due to bad weather and the estate remained in trouble through to 1359-60 only to eventually recover to pre Black Death levels by 1363-64.

*No one is certain when the name ‘Black’ was attached. It has been suggested it arose from the putrefying flesh or the black blisters.

Sources:

- Ziegler’s, The Black Death Folio Society, London.

- Medieval Flegg by Barbara Cornford.

- Diary of a Parish Priest, 1160-2001 by Andrew Sangster.