Vicars of St Mary the Virgin, Martham

The earliest reference we get to any vicar at Martham is from Blomefield(1) in about 1160. At that time the church was a round tower predecessor to the existing building and its patrons were the Gunton family who owned Moregrove Manor which included the church. In about 1160 Roger De Gunton gave the church to the Priory and Convent of Norwich for the redemption of his soul and when making this gift Adam de Walsingham was appointed as the Vicar.

In 1224 Matthew de Gunton, a descendant of Roger de Gunton, held possession of Moregrove Manor. As Lord of the Manor of Moregrove Matthew had the right to appoint vicars (called an advowson) but in 1224 he gave the right to the Monastery and Priory at Norwich Cathedral on the understanding that the monks would pray for his soul and the souls of his family and servants. As a result of this gift St Mary the Virgin comes under the patronage of Norwich Cathedral and the Cathedral remains responsible to this day for appointing parish priests.

The earliest known vicars appointed by the Cathedral were Thomas de Langdale (or Langele) and John de Eccles. Both were appointed in 1311 by the Prior & Convent of Norwich. Nothing more is known about Thomas de Langdale but presumably he died in 1311 because John de Eccles was appointed as vicar later in the same year. He seems to have lasted longer than his predecessor because it was ten years later, in 1321, that William de Wicklewood was appointed as vicar.

William de Wicklewood again only lasted for two years and in 1323 Roger de Kirkeby was noted as being the Parish Chaplain at Martham(1) and had a licence from the Prior and Convent of Norwich to teach grammar to 20 boys. It is more likely that this was intended as a way of teaching the scriptures to boys in the hope that they may eventually enter the church. Roger de Kirkeby remained as vicar until 1342 but it is not known if he retired or died.

In 1342 Thomas de Halvergate was appointed as vicar. Towards the end of his tenure the Black Death arrived in 1348-1349 which killed about a third of the population. It is likely that the plague hit the clergy of Martham directly just like the rest of the community as Thomas de Halvergate died in 1349 at the height of the plague locally and he was replaced by William de Wardeboys in the same year. Tragically, he must have succumbed as well as another vicar, John Spyre, took his place in the same year. The plague had far reaching economic effects; there was a shortage of labour and men began to move from village to village to get better wages, undermining the institution of serfdom and influence the Church had on their lives.

John Spyre (or Spire) survived the ravages of the Black Death and was the vicar from 1349 until 1375. In his Will he made a bequest of money to Martham Church. His will was in Latin in 1374. It was translated into English by Barbara Cornford and reads as follows: –

“In the name of God Amen. Thursday before the Assumption of the Blessed Mary 1374, I, the said John Spire, Vicar of Martham made my will in the following way – In the first place I leave my soul to God and the Blessed Mary and all the saints, and my body to be buried in the chapel of Saint Blide at Martham…I leave to the use of that church 10 Marks”.

Although, he made other bequests, half of his estate – 10 marks or £6 13s. 4d. (£6.66) was left to St Mary’s.

John was buried in the Chapel of Saint Blide which is situated on the south side of the church in about 1375.

John Spyre was followed by Andrew Read. During the time that Andrew Read was vicar the Peasants Revolt took place. The Revolt started in Essex in 1381 when people began to refuse to pay Poll Taxes imposed to help pay for the war against France. The peasants were not just protesting against the Poll Tax. Since the Black Death, poor people had become increasingly angry that they were still serfs. They demanded that all men should be free; that harsh labour laws should be abolished and for a fairer distribution of wealth. On our doorstep the local population would have been well aware of the last major resistance of the Peasants Revolt at the battle of North Walsham fought between the peasants and the forces of Henry le Despencer, the Bishop of Norwich on 25th/26th June 1381. Poor folk would almost certainly have been supportive of the revolt which must have undermined the authority of Andrew Read in the community.

Andrew Read’s time as vicar was drawing to a close in 1389 and he was followed by William Northales, who in turn was followed by Robert Tynmouth in 1392 and John Lanham (alias Saltby) in 1405.

In the early 15th century beliefs in the established church were being more and more widely questioned. This was led, on the Continent, by a group of heretics called the Lollards. They did not agree with the wealth of the Catholic Church; the ‘selling’ of indulgences for the forgiveness of sins and wealthy people buying relief from sin in the hope of everlasting life. They also rejected the Pope as head of the Church. The Lollards believed in simple life, being guided by the Bible in Christian life and obedience to God and they were led by a man called John Wycliffe. In 1428 a Martham women by the name of Margery Baxter was accused of being involved with the heretic leader John Wycliffe by providing him with a safe house in her home; the hiding of illegal books and entertaining a group of Lollards from Loddon & Earsham. All this in the shadow of St Mary’s under the care of John Lanham.

John Lanham appears to have been the vicar for a long time, unless the records miss intervening postholders, as it was not until 1449 that William Bishop followed him. William did not last long because he was succeeded in the same year by Edward Berry. Edward was followed by Robert Allen but it is not known exactly when, only that Robert died in 1487 and there is a heart-shaped brass in his memory that has the inscription “Post tenebras spero lucem Laus deo: neo” (After darkness I hope for light, Praise be to God).

Summary of the pre-Reformation Period of Vicars

We know almost nothing about the above priests as individuals but by looking at the circumstances at the time we can perhaps gather an idea of what their life must have been like. In the 13th century the church had different messages for its members depending on their wealth and social status. England was still largely feudal as established by William the Conqueror. All land was owned by the King and was in his gift. In return for loyalty and for supplying men at times of war parcels of land or `manors` were given by the King to favoured Earls who often held lands in various parts of the country. Similarly, the Church was ruled by the Pope who would appoint Bishops for similar favours and in turn the Bishops and Priors would appoint clergy mostly based on favouritism. The majority of people in a rural area like Martham were peasants although there was a larger number of freemen in Martham than the average for the country. For them the church bestowed the message of saving the soul through the value of suffering. This meant that they were meant to suffer because of God’s divine will whereas the church believed that those of higher class, the noble and wealthy, were meant to have divine blessings throughout life although many of these had to be purchased.

At that time the church governed how people lived their lives and how they understood the world. All major life occasions – birth, marriage and death – happened in the church. It governed people’s social lives, punished moral wrong-doings and marked the passing year with a calendar of festivals. In the 1300’s all Christians were part of the Roman Catholic Church. In church, services were held in Latin and the Bible was written in Latin. Most ordinary people could not read, so Bible stories were told in beautiful images and stained-glass windows or in ‘mystery plays’ on special holidays.

On a lighter note, this was also the period that saw the building of a new church in Martham. The new, present church was built between about 1377 and 1450. Andrew Read, William Northales, Robert Tynmouth and John Langham must have presided over the building of the new church which replaced the older 12th century round-towered one, the footings of which were discovered in 1999 during the lowering of the floor of the west tower.

The Rev. Thomas Hitton, who died in 1530, was said to be a parish Priest at Martham but there is little proof. He is generally considered to be the first English Protestant martyr of the Reformation and you can read more about him by clicking on his name to follow the link.

For centuries all Christians living in western Europe were Catholics. Historians now believe that most people in England and Wales were happy with the Catholic church before the Reformation of the 1534-1540. There were some problems but generally the Catholic church was popular. It was extremely wealthy. For centuries people had donated land and money to it. With this money it built monasteries and convents. They were not just homes for monks and nuns, but also schools and hospitals. They gave charity to the poor. Some were important centres of learning with large libraries. Then came the dissolution of the monasteries. Essentially it was politically driven because Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his Spanish, and Catholic, wife Catherine of Aragon. The Pope dithered and refused to make a decision. Henry decided to take matters into his own hands. Using laws passed during the Reformation Parliament between 1529 and 1536 he declared himself Supreme Head of the Church in England and granted his own divorce. He also needed money. With his new chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, he declared the church under the Pope to be corrupt and closed down (dissolved) the religious houses and took their riches. The Pope condemned Henry’s actions but could not stop him. The Catholic church lost most of its wealth in England and all of its independence.

The 1534 Act of Supremacy(2) gave rise to the dissolution of the monasteries and changed the English church forever. From then until now Martham vicars were appointed by the Dean & Chapter of Norwich Cathedral. There are gaps in the records of vicars at Martham during this period which is probably because of confusion at the time of the Reformation rather than a long-term vacancy. On the Dissolution the patronage of the church came to the Crown (effectively Henry VIII himself). The great Priory & Convent of Norwich was dissolved on 5th April 1539 and the power to appoint vicars at Martham was vested in the Dean & Chapter of Norwich Cathedral (the former Priory). In 1540 the first recorded vicar appointed by the Dean & Chapter at St Mary’s was John Harridance.

John Harridance (or Harrydans). Vicar 1540 to 1559.

According to the antiquarian Francis Blomefield(1) John Harridance was the Vicar of St Mary the Virgin from 1540 until his death is 1559. John’s Will was proved at Norwich in 1559 but nothing further is known about him other than he lived through turbulent times. In 1539 the great monastery of Norwich had been dissolved and the patronage of the church went to the Crown with the last Prior, William Castleton, becoming the first Dean of the new establishment. So, it appears he must have appointed John as vicar at Martham the following year.

Robert Foulsham. Vicar from about 1558 to 1603.

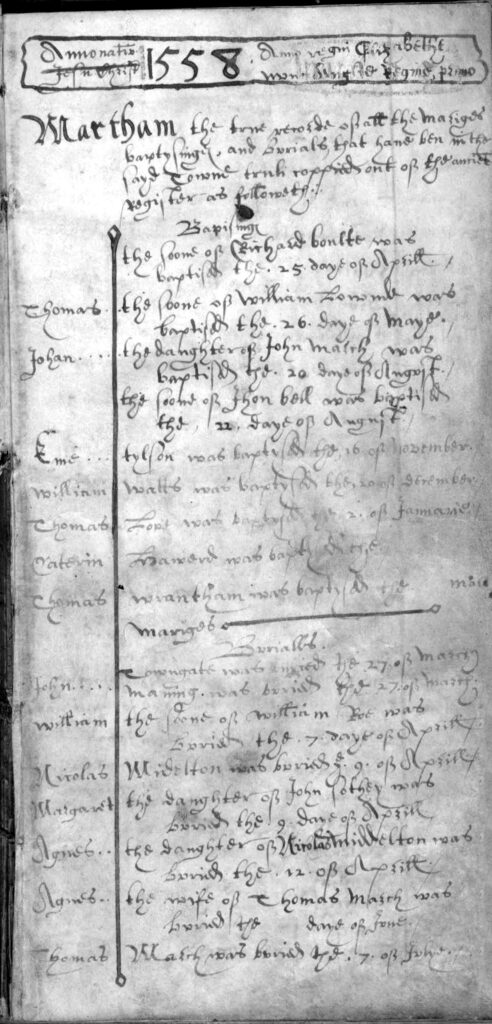

By an Act of Parliament of 1538 parish priests were required to keep records of all baptisms, marriages and burials which occurred in their parishes. The oldest surviving register for Martham dates from 1558 and is signed by Robert Foulsham the vicar so it seems there was some overlap between John and Robert. Robert may have been his curate. Nothing further is known about Robert other than that he died at Martham in 1603 and was buried in an unknown grave at St Mary’s on 30th January 1603.

Robert (or Ralph) Ovington from 1603 to about 1641

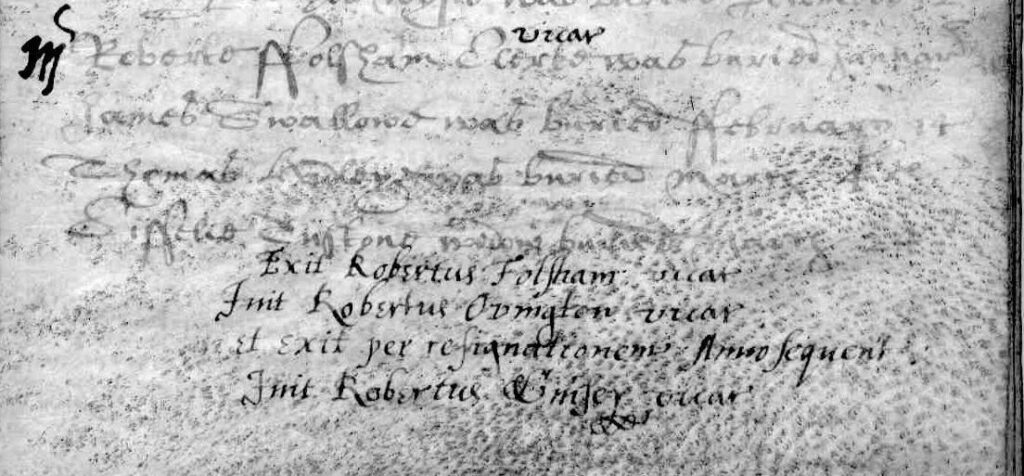

The above copy of the 1603 register shows the burial record of Robert Foulsham with the new vicar Robert Lynsey (also known as Robertus Linseye) instituted as vicar on 10th March 1603(3). He was quickly followed by Robert Ovington who was appointed vicar by the Dean & Chapter of Norwich Cathedral on 6th August 1603. He was a Caister man and does not appear to have lived in Martham. He was married to Alice Harrison in Caister on 27th September 1579. They went on to have at least four children who were all baptised at Caister. They were:-

- John, who only lived for about a month in 1585.

- Richard, baptised on 9th July 1587.

- Thomas, baptised on 12th January 1588, and

- Peter, baptised on 14th February 1592.

Robert Lynsey seems to have acted as a curate to Robert Ovington during his term in office although the latter was from Caister and Robert Lynsey may have been employed by him to work at Martham. Robert Lynsey died at Martham in 1641 and is buried in an unknown grave at St Mary’s.

During their time working in the church they would probably have been aware that in 1612 the Baptist Church was established in London and in 1620, as a result of religious persecution, the Pilgrim Fathers set sail in the Mayflower to the New World.

From here onwards a little more personal information is known about each vicar and so there are individual pages for them that can be seen by clicking on their names. They were vicars between the dates shown.

1642-1669 John Spendlove (also known as Johanos or Johannes).

1668-1669 Lionel Gatford is listed as being the vicar at St Mary’s from 5th January 1668 to 28th August 1669 according to the Clergy of the Church of England Database(3) but as this period overlaps John Spendlove and Benjamin Lawrence it seems he never took up the appointment. There are no entries recorded in his name in the church registers.

1669-1683 Benjamin Lawrence.

1683-1694 Henry Curtis (also known as Harry).

1695-1727 Richard Marris.

1728-1758 James Savage.

1758-1792 Thomas Bowman.

1792-1834 Paul Whittingham.

1834-1876 George Pearse.

1876-1905 George Merriman.

1906-1921 Herbert Webster.

1921-1928 Nathaniel Temple Hamlyn (former Bishop of Accra).

1928-1947 John Herbert Griffiths.

1947-1953 William Douglas Stenhouse.

1954-1959 Harry Cecil Kemp.

1960-1967 Peter Harry Rye.

1968-1976 Ronald Cooling.

1976- 1989 Edgar Alan Cunnington.

1990- 2004 Peter Stanley Paine.

2006-2013 Jeanette Crafer.

2015- 2017 Karen Rayner.

2018-2024 Dr. Steven Sivyer

April 2024 – Deborah Walton

In addition to the above there have been a number of curates who have greatly contributed to St Mary’s and its parishioners. Some of them are listed below and more about them can be read by clicking on their names.

Name: Lifespan: Dates a Curate.

Thomas Dockwra (1676-1719) curate 1716-1718.

William Mackay (died 1752) curate from 1721 to 1723.

Richard Spurgeon (1767 to 1842) curate from 1797 to 1811.

Thomas White Holmes (1790-1872) curate 1814-1835.

Fisher Watson – curate 1814.

Thomas Corbould (1796-1869) curate 1836 to 1850.

David Hinderer (1819-1890) curate from 1870 to 1873.

Joseph John Gurney (1848-1890) curate from 1873 to 1876.

Jean the wife of Rev. Edgar Alan Cunnington recorded these memories of arriving at Martham when her husband took up the post of Vicar: “My husband, Alan, had applied to the Dean and Chapter of Norwich for the post of Vicar to St Mary the Virgin and the small church at West Somerton. Alan’s application was successful and we arrived at the Vicarage very late on 4th May 1976 from Islington in London, close to the A1 we had become used to noisy traffic and had an international lorry park just opposite the house. The silence in Martham was startling and we froze in fright when upon opening the back door of our Bedford van a box of cutlery fell out with a clatter! We expected somebody to come storming out of the houses using colourful expletives. Totally black and without street lights the silence remained and nothing happened. We had torches in the van and the headlights, so gained access to the house to spend the night in makeshift beds previously prepared waiting for the furniture vans to arrive the next day.”

Definitions

The following definitions of distinctions between the various lower ranks of Anglican professionals may be helpful.

Clerk in holy orders: Clerk in holy orders is a generic description of any member of the Anglican clergy, indeed clergy is an abbreviation of the term. The term can be applied to a Bishop and to a porter.

Incumbent: An incumbent is normally the parish priest and is one with legal possession of the church and assets.

Rector: A rector is a parish priest distinguished from vicars by receiving directly the monies of the church, as opposed to being paid a salary by a superior.

Parson: A parson is an incumbent who usually lives in a rectory or parsonage owned by the church.

Curate: A curate is literally one who has been invested with care for souls but has come to mean an assistant priest or deacon.

Vicar: Traditionally a vicar was a parish priest who received a salary and was the assistant to a rector. The term is derived from the word vicarious as a vicar was one who acted on their employer’s behalf.

Sources:

(1) An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 11.

(2) November 1534 Act of Supremacy established English monarchs as the head of the Church of England.

(3) https://theclergydatabase.org.uk/

Appointment information courtesy of the: Clergy of the Church of England Database at https://theclergydatabase.org.uk