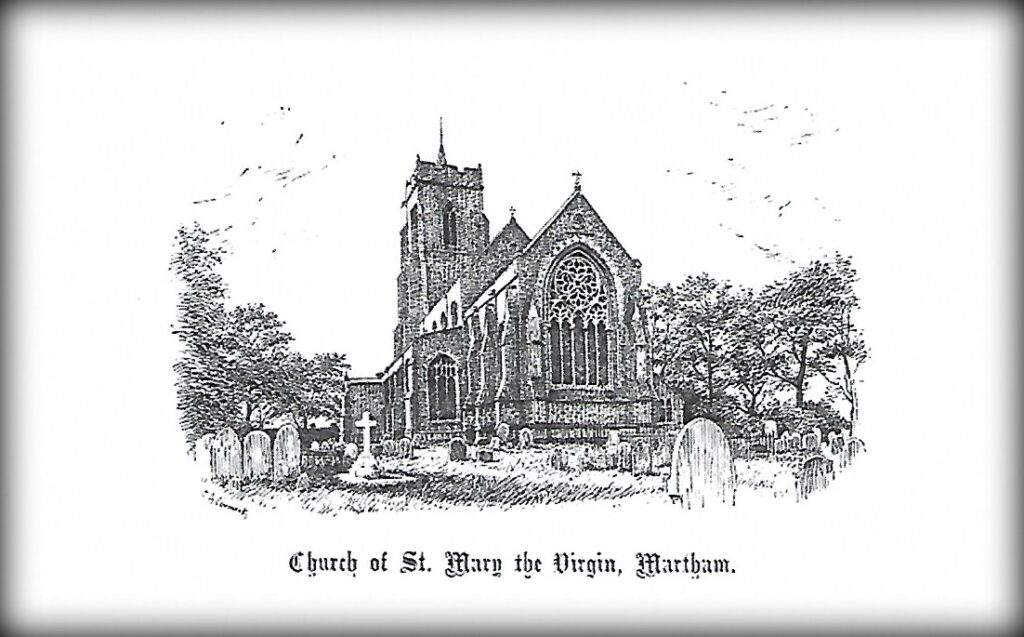

St Mary the Virgin, Martham

This is a long page providing information about the most historical building in the village. Consequently I have broken it down into sections that you can take shortcuts to if you wish. Just click on a heading, which are:

- Chronology

- Summary of the history of the building

- Take a walking tour around the building

- Theory of who built the original round tower church

- Who Built the Church We See Today?

- Photo gallery

You may also like to follow these related links:

Read the strange story of ‘Base born Biggs’ HERE

Read about the Burraway mystery HERE

Details about the church graveyard can be found HERE.

Details about the original Vicarage can be found HERE.

Read about the mystery of a lectern in the name of Rev. William Tristram Edward Cary HERE.

Read about the unique, lost medieval altar cloth that once graced the altar at St Mary’s HERE.

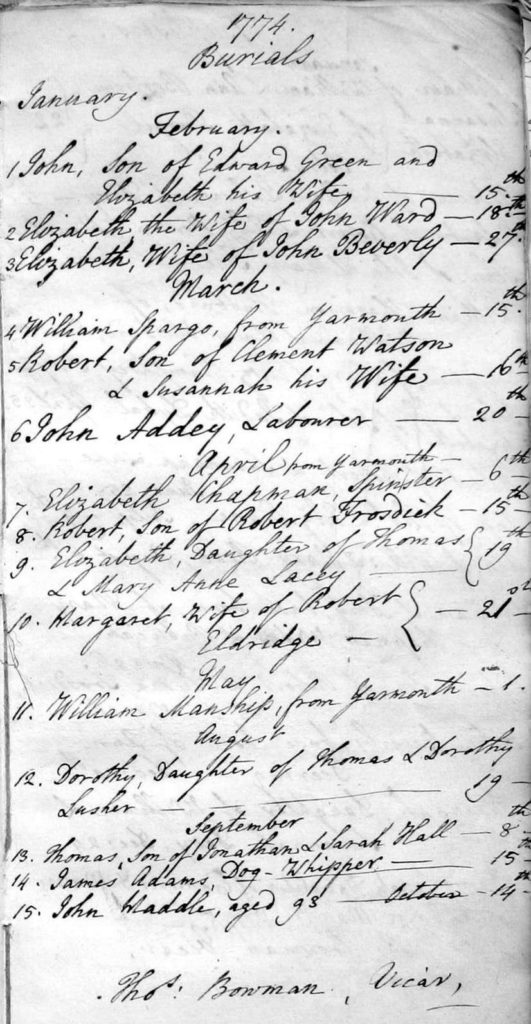

But first, just to be a little more lighthearted, what is a dog whipper?

A dog whipper was a church official charged with removing unruly dogs from church and grounds during services. Those employed for the position were given a three-foot-long whip and a pair of dog tongs with which to remove the animals. They were given the task of keeping stray animals away from the church so that priests could carry out their duties unhindered. The whip was utilized both for enforcement and as a deterrent while the tongs enabled the whipper to clasp a problematic animal from a safe distance. It was not uncommon for household dogs to accompany, or at least follow, their owners to church services at this time. If at any point they became loud, fought with other animals, attacked congregation members, or were otherwise disruptive, it was the job of the dog whipper to remove them from the church as well as to allow the service to continue in peace.

Preposterous as it may seem St Mary’s had at least two dog whippers. The church registers reveal this from the burial entries for James Adams on 15th September 1774 – see copy on the left – and for John Ward who was buried on 19th April 1782. The registers show both were dog whippers at St Mary’s.

Chronology

1075 – Burial place of St Blide.

1086 – Martham had a round tower church according to the Domesday Book.

1160 – Roger De Gunton, of Moregrove, gave the church to the Priory and Monastery of Norwich Cathedral.

1224 – Matthew De Gunton gave nine acres of land to the church and the advowson of St Mary’s to the Monastery and Priory of Norwich Cathedral.

1292 – Roger De Gunton gave a house and 12 acres of land to St Mary the Virgin.

1300 – The Parish chest dates from about this time.

1300- 1470. Most of the present church dates from this period (the original chancel was replaced later).

1370 – The castellated tracery of the west window was installed.

1375 – The former Vicar John Spire left 10 marks (£6 13s 4d) to the church.

1377-1450. The embattled, perpendicular style tower was built.

c1450 – Local man Roger Clarke paid for a stained-glass window (it disappeared during later restoration of the chancel).

1456-1469. The chancel was built costing £66 13s 4d according to Cathedral cellarer records.

1552 – There are four bells dating from this time.

1717 – One of the bells was recast.

1855-1861. The new Gothic revival style chancel was built.

1990-2000. The bells were restored and reinstated in a strengthened gallery above a new ringing landing.

Summary of the history of the building

A church is mentioned at Martham in the Domesday Book of 1086 together with 50 acres of land to provide an income for the parish priest. At that time Martham also had two manors. One manor was centred at Martham Hall (Hall Road) and was held by the Bishop of Elmham as part of his income. The other manor, centred at Moregrove, was held by another ‘lord’ who also held the right to appoint the rector at St Mary’s (an advowson). This manor was held in 1224 by Matthew de Gunton who in that year gave the advowson to the Monastery and Priory at Norwich Cathedral on the understanding that the monks would continue to pray for his soul and the souls of his family and servants. As a result of this gift Martham comes under the patronage of Norwich Cathedral and the Cathedral is responsible for appointing the parish priests.

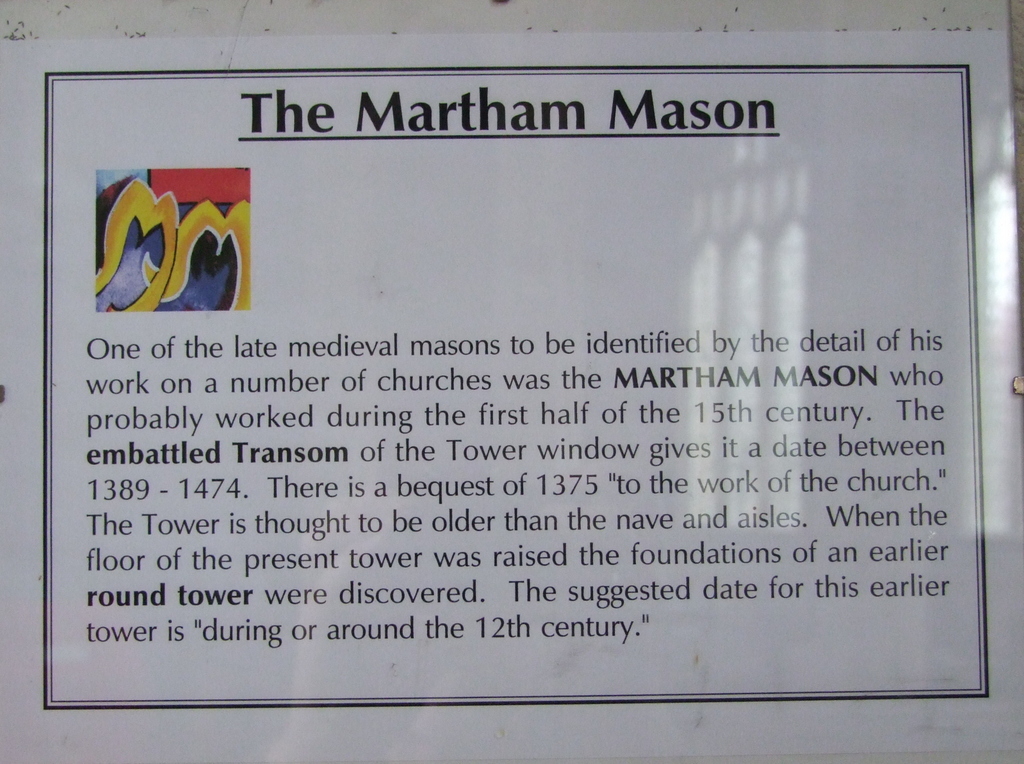

The church was built during two periods. The tower and nave were built between about 1377 and 1450 in the perpendicular style of that era. In those days the stonemasons travelled to wherever work was taking place, leaving their mason’s marks on the stonework. One of these left marks on several churches in east Norfolk and became known as ‘The Martham Mason’.

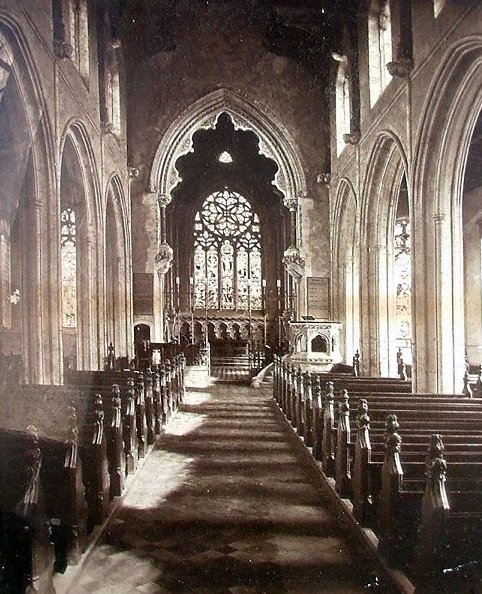

The 1456-1469 chancel became totally dilapidated and was rebuilt between 1855 and 1861. The new chancel is a magnificent example of the gothic revival architecture of that period. The architect was Philip Boyce whose brilliant design was exhibited at the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1856.

There are very good 15th/17th century woodwork features and fine Victorian fittings in the chancel. The church has a 15th century ‘seven sacrament’ font.

In 1999 work was carried out on the tower floor to install drainage and the footings of a round tower probably dating to the 12th century were exposed indicating that there had been an earlier church on the same site as the present one. That may have been the church mentioned in the Domesday Book. During the excavations medieval graves were also identified as well as a small lead-melting pit containing medieval window glass. Also flint flakes, medieval pottery sherds and a pit for melting lead window cames plus remains of Roman tiles and a lava quern were found.

St Blide of Martham

Martham is famous as the burial place of St Blide early in the 11th century. St Blide was the mother of St Walstan and was born about 1075, she was related by marriage to the Royal Family of the Kingdom of Wessex. The chapel in Martham Church where she was buried was dedicated in her honour. In 1522 Robert Fullere a tanner of Norwich gave money for repairs to Martham Church ‘where St Blide lyeth’.

When he died in 1375 the then vicar, John Spire left 10 marks (£6 13s 4d or £6.66) to Martham Church which may have prompted the start of the re-building of the present church beginning with the tower although this would have been insufficient to finance re-building the whole church. A project on that scale, at that time would have required detailed drawings and contracts to have been drawn up. The place to look for those would be in the records of the Priory and Monastery at Norwich Cathedral as it was the patron of the church. Their records reveal that their master mason Robert Everard was working on St Mary’s chancel during the years 1450 to 1480. Another important contributor to the cost of the building may have been local landowner Roger Clarke to whom a stained-glass window was dedicated. You can read more about this under the section called Who Built the Church We See Today?

There is a Parish Chest that was made in about 1300, its lid carved from a single tree truck.

Take a walking tour around the building

My thanks to Ann Meakin and Chris Harrison who provided all the information in this section.

Starting from the south porch and going round the west side of the tower look up at the magnificent buttressed tower 98 feet in height and topped with a small lead covered spirelet supporting a gilded cockerel added in the early eighteenth century. The tower would have taken many years to build as the mortar between the flints had to settle and become firm before the next layer was added. Shuttering would have been used to support the walls as they went up. This would have been supported by wooden scaffolding poles inserted through the walls. You can see a very few places where a brick has been inserted. These are the put log holes that show where the original scaffold pole would have been.

There is a frieze of decorated flints around the base of the whole building.

The west door is now glass panelled. This door was put in as part of the Millennium restoration project. Behind it inside, the older door has been retained.

Look up and notice the the castellated tracery of the west window. Experts think this is typical of work from the late 1370s.

Continuing round you will find the north door. It has remained closed for many years but would originally have been opened for the processions that took regularly place in mediaeval times. You can admire the delicate window tracery of the nave typical of that used in the 1400s.

The small room adjacent to the north wall of the chancel is the vestry. When you reach the chancel notice how different the window tracery is. Continuing round the east end to the south side, notice the flint work in the walls. This differs considerably between the chancel and nave. Both are most skillfully done.

The vaulted porch is very fine. You can see from the small window that there is a room above the entrance. This is approached by a steep staircase inside the church. It has had many uses over the centuries.

As you enter the church, admire the south door with its original iron work and very delicate tracery. That at the top is the original however that at the bottom is a skillful replacement during the 19th century restoration.

Inside the Church

The Tower is finely proportioned, with a spiral staircase of 119 steps. The arch between the tower and the nave is exceptionally fine and allows the maximum of light to flood into the church from the west window. At the millennium a new development was constructed in the tower in order to provide, on the ground floor, a kitchenette, a toilet and a small meeting room, on the first floor, a larger meeting room and above that a new bell-ringing chamber. The screen in English Oak was made and decorated in blue and gold leaf to reflect the Victorian chancel screen. The architect and designer for this was Ruth Blackman of the firm Birdsall, Swash and Blackman of Hingham, Norfolk. The work was carried out by the firm A.J. Cooper of Calthorpe, Norfolk.

The Nave is a very fine example of perpendicular architecture with a splendid clerestory. It is filled with Victorian pews that replaced the box pews and three-decker pulpit of earlier centuries. A few pews in the north and south aisles have a number of 15th century poppyhead bench ends incorporated into them (shown left). Among them is a Green Man, a puritanical man with a tall hat, a pair of fishes and other fascinating figures. One pair of benches in the Prayer Corner of St Blide at the east end of the South aisle have poppyheads with carved bells and the inscription A.M. for Ave Maria, a traditional monogram of the Virgin Mary to whom the church is dedicated.

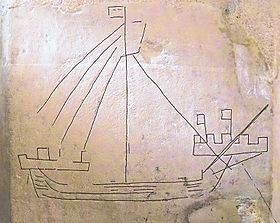

On the column nearest to the south aisle east window you will find a graffiti image of a ship in full sail skilfully scratched into the stonework about three feet from the floor.

To the north side of the chancel screen is a small doorway which once led to the medieval rood loft above the screen which spanned the former chancel arch.

The nave has a very fine hammerbeam roof with eleven pairs of angels. It was fully restored during the Victorian restoration of 1855-61. Close inspection of the angels reveal that some carry instruments of the Passion of Christ, while others are holding musical instruments. On the north side beginning at the tower arch you will see:

- An angel with a shield showing the cock that crowed after Peter had three times denied that he knew Jesus.

- An angel holding a small instrument of pipes.

- An angel playing a stringed instrument.

- An angel with a shield showing the seamless robe worn by Jesus at the crucifixion. (After Jesus’ body was taken down from the cross the Roman soldiers cast lots to decide who should have it.)

- An angel holding a scroll or a small instrument of pipes?

- An angel with a flute.

- An angel holding the pincers that would have been used to remove the nails from the cross when Jesus’ body was taken down.

- An angel with a scroll.

- An angel carrying the ladder used when Jesus’ body was taken down from the cross.

- An angel holding a small organ.

- An angel carrying a cross.

- On the south side beginning at the chancel arch you will see:

- An angel holding a crown of thorns.

- An angel holding a ram’s horn.

- An angel holding the hammer and nails used to fix Jesus’ body to the cross.

- An angel holding an early violin or rebec.

- An angel with a spear.

- An angel holding a crown of thorns.

- An angel with a harp.

- An angel with a scroll.

- An angel with the rope used for the flogging of Jesus.

- An angel holding a shield showing the five wounds of Jesus on the cross.

- An angel with hands held in prayer.

The corbels supporting the roof beams have beautifully carved heads on them.

The tracery of the windows at the east ends of the aisles is exactly the same as the tracery of the clerestory windows of the magnificent church of St. Peter Mancroft in Norwich. The same mason may have worked on both.

Stained Glass

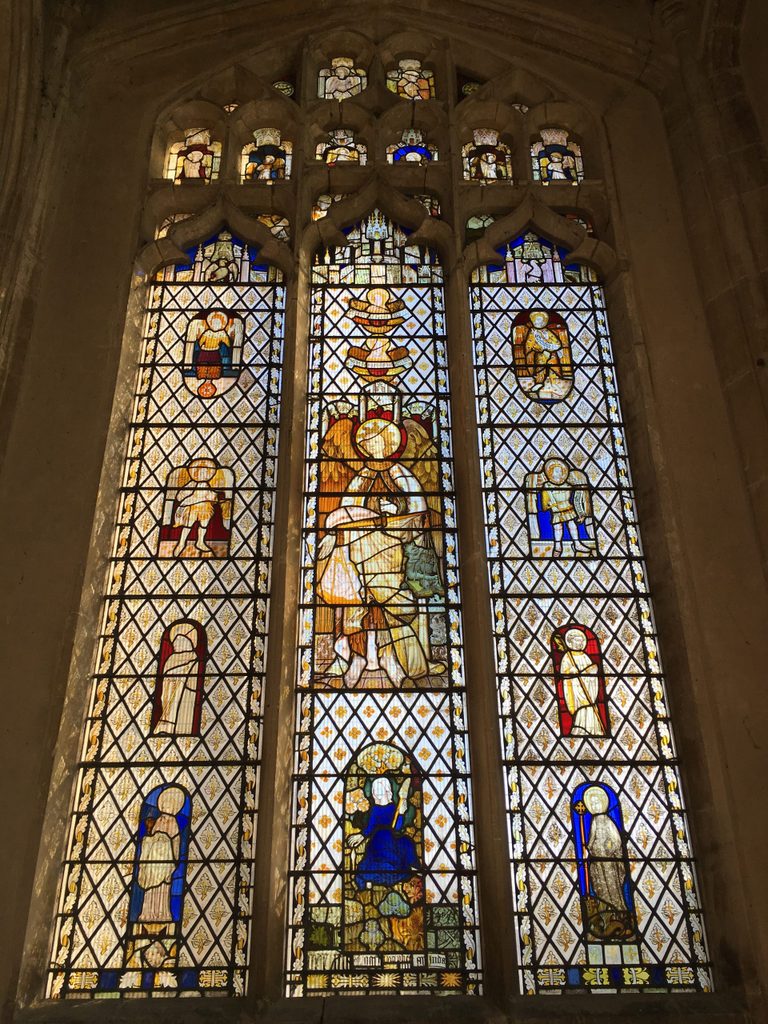

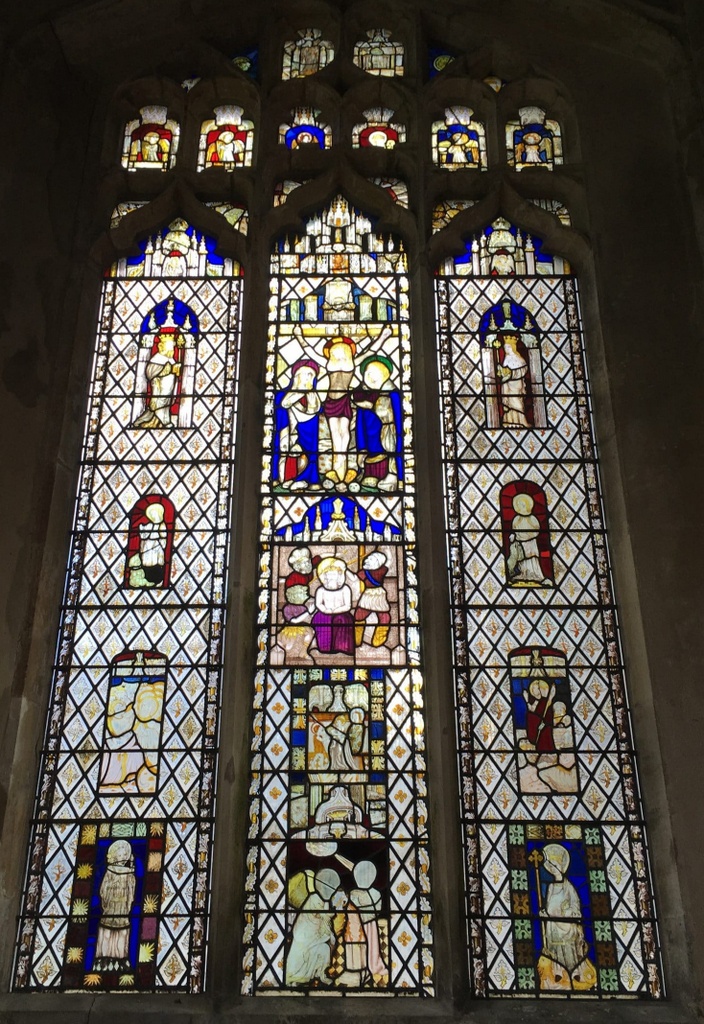

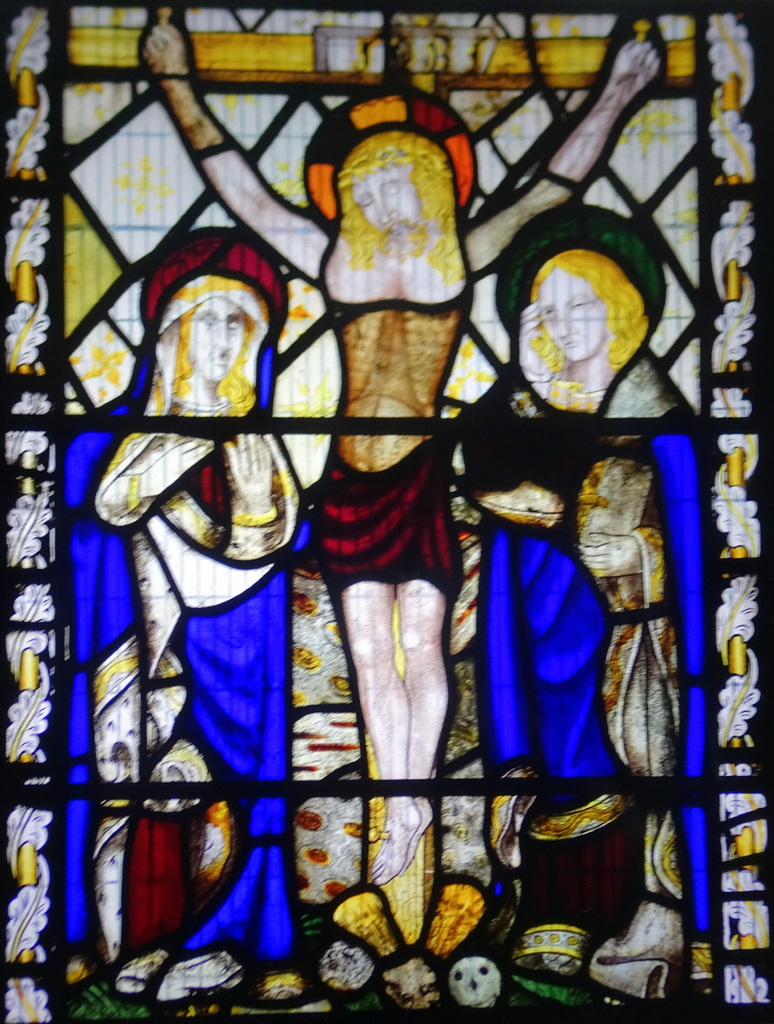

Most of the remaining medieval stained Flemish glass and glass of the Norwich School was collected during the 1855-61 restoration and placed in the east windows of the aisles, however not always correctly. When the original windows were installed people would have known exactly who the people depicted were and the scenes portrayed. Nowadays however there is some uncertainty about some of them, although the following information is as accurate as possible from our current knowledge.

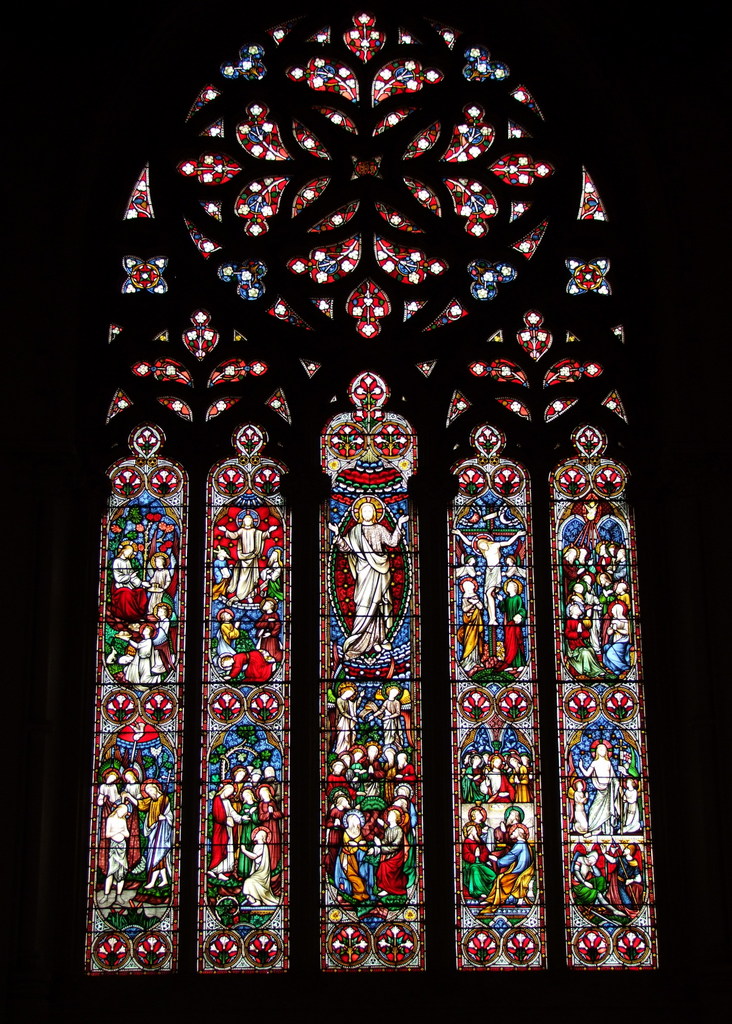

The stained glass of the great east window of the chancel was installed during the rebuilding of the chancel in 1855-61. It is by Hardman & Co. of Birmingham. Depicted are scenes from the life of Christ, with the Ascension in the centre. All of the other chancel windows installed in later years are also by Hardman and Co., and were given by members of the families of Jonathan Dawson and George Pearse.

In the East Window of the South Aisle.

i. The top windows of the panels contain eagles.

ii. The panel on the left has at the top a seraph on a wheel.

iii. Below that is St Michael with scales.

iv. Below that is St. James the Great as a pilgrim returning from Compostella carrying his pilgrim staff, rosary beads and with a cockle shell in his hat.

v. Below that is St. John the Evangelist? Or the Baptist?

vi. At the bottom is a grotesque figure with a staff in his eye?

viii. The centre panel has at the top, angels with scrolls.

ix. Below that is St. Michael weighing up the bad and good in souls. Note the naked souls in the scale pans on one side and the devils in the pan on the other.

x. Below that is Eve spinning – shown left. (Unfortunately, the corresponding stained glass window of Adam delving with his spade in the Garden of Eden – shown right, plus Adam & Eve walking through the Garden of Eden, and other glass was taken to Mulbarton Church, 25 miles away, in the early nineteenth century by the Martham Curate Rev. Richard Spurgeon who became rector at Mulbarton. This glass can still be seen in the East window of Mulbarton Church).

xi. The panel on the right has at the top a cherub.

xii. Below that is an angel with a sword depicting Principalities.

xiii. Below that is a tonsured ecclesiastical dignitary with a staff and book.

xiv. At the bottom is St. Margaret of Antioch without a crown but with a dragon at her feet.

The East Window of the North Aisle.

xv. The top left panel is of King Edward III. (Edward III was a much loved king who died in 1377 after reigning for 50 years).

xvi. Below the King is St. Juliana with the devil on a chain.

xvii. Below that is the Ascension with people looking up to heaven.

xviii. At the bottom is St. Edmund – King of East Anglia, martyred by the Danes in 869. (Could this be a reference to the earlier round tower church?)

xix. The middle panel shows at the top the Crucifixion.

xx. Below that is Christ wearing the crown of thorns, being mocked before his Crucifixion.

xxi. Below that is The Virgin Mary holding Jesus with the boy St. John the Baptist standing at her feet.

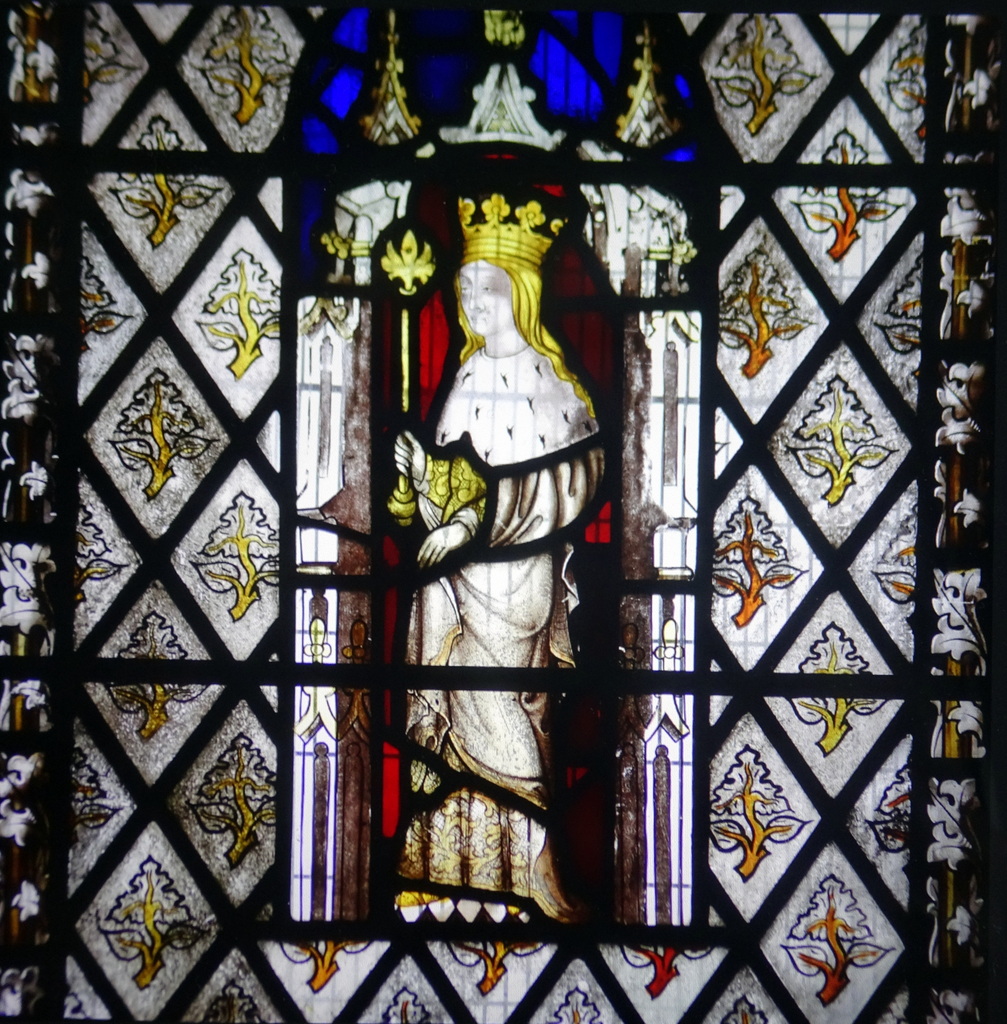

xxii. The top right panel shows Queen Phillipa.

xxiii. Below that is either St. Agnes or St. Anna.

xxiv. Below that is possibly the Resurrection with Christ still wearing the crown of thorns.

xxv. Below that is St Margaret of Antioch wearing a crown.

Font

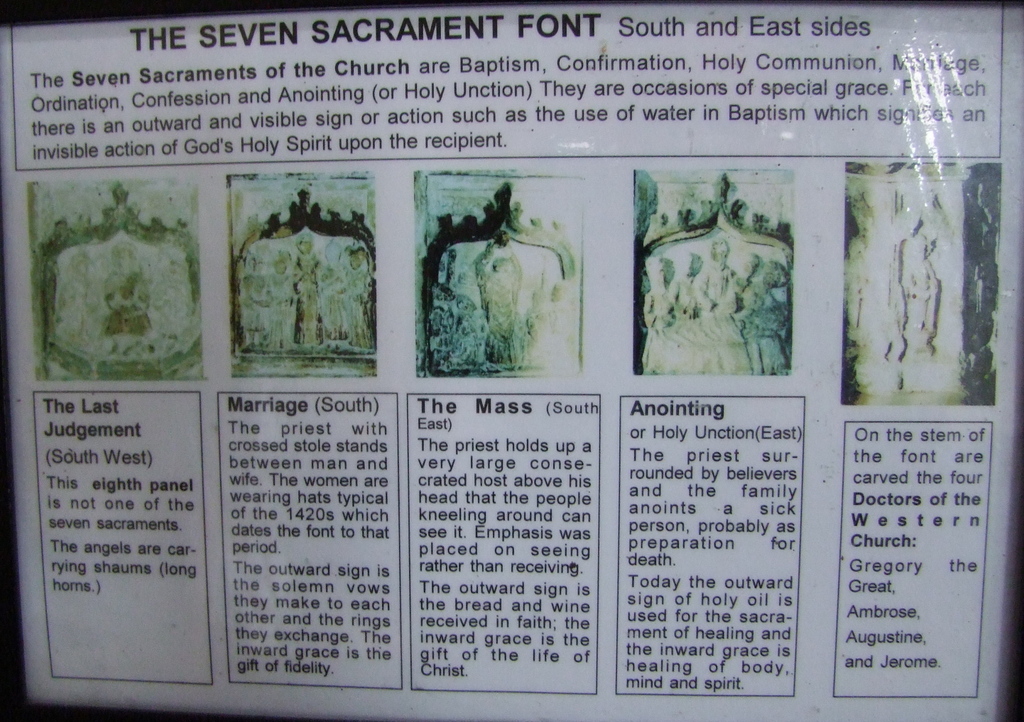

A fine 15th century seven sacrament font stands at the west end of the nave. Seven sacrament fonts were sometimes placed in churches where there had been a strong influence of the heresy of Lollardy, in order to emphasis to people the Church’s teaching about the sacraments considered essential to the living of a good Christian life.

Standing facing east you will find that the panel in front of you is The Last Judgement with angels blowing shawms. Moving to your right you will find Ordination, Marriage, Holy Communion, Holy Unction (the anointing of a person near to death), Baptism, Confirmation (with the Bishop wearing his mitre), and Penance (with the devil running away) Around the stem are carved figures including the four doctors of the Western Church.

The Organ, was built by Forster and Andrews of Hull in 1871 was removed from the base of the tower in 1999 and moved to its present position at the west end of the north aisle. It is a tracker action organ – one of the finest to be found in a country church, with two manuals and pedals and 14 stops.

The Parish Chest with its lid carved from a single tree trunk is thought to date to around 1300. It was until recently, used to store the Parish Documents and valuables in secure keeping, however these have now been deposited at the Archive Centre at Norwich.

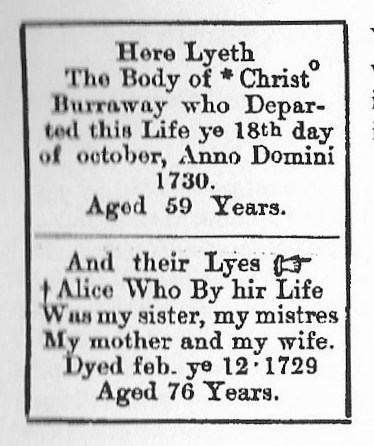

The Burraway Grave Slabs now lean against the south wall. They once lay on the floor of the nave marking the burial places of Christopher and Alice Burraway. Christopher Burraway died aged 59, on 18 October 1730; he was a churchwarden and his name is inscribed on one of the bells in the tower. His wife, Alice Burraway, died aged 76, on 12 February 1729. The strange wording on Alice’s grave slab has puzzled many in later centuries. It reads:

“And their lyes Alice who by hir life was my sister, my mistres, my

mother and my wife. Dyed feb. ye 12. 1729 aged 76 years”.

In 1874, Mr James Harrison of Great Yarmouth did an enormous amount of research in parish registers, endeavouring to find an explanation and concluded that Christopher Burraway (the son of Christopher) was born at Potter Heigham about 1672. His mother Mary née Lane, after being widowed married Gregory Johnson of Martham in 1674.

(Alice’s first husband was William Ryall whom she married in 1679 at Norwich Cathedral. Alice’s second husband was Gregory Johnson, a churchwarden at Martham whom she married in 1693. He was buried at Martham on 28th June 1700. After being twice widowed, she married Christopher the stepson of her second husband in 1702 at Norwich Cathedral. A rather different story appears on cards on the bookstall).

The Chancel was totally rebuilt during the restoration of 1855-61. It is similar to the finest of chancels you would have found in a medieval church before the Reformation. The architect who was commissioned with carrying out the work was Philip Boyce of Cheltenham whose brilliant design was accepted for display at The Royal Academy Exhibition of 1856. The decorative carving including the pulpit was done by the sculptor Henry Earp (brother of the more famous Thomas) and also the young Benjamin Grassby. Many animals, beasts and flowers can be seen around the chancel walls including the crowned pelican shown on the left.

A small heart-shaped brass, in memory of Robert Alen a former Vicar who died in 1487, is fixed on the south wall of the chancel. It would have been on the slab that marked his grave in the former chancel that was demolished. The inscription reads: ‘Prost tenebras spero lucem: Laus deo: neo’ – which translates as ‘After the shadows I hope for light. Praise be to God.’

Rev. Jonathan Dawson

On the north wall is an Easter Sepulchre with on the back wall a dedicatory inscription to the Reverend Jonathan Dawson, in whose memory the complete restoration was carried out at the expense of his widow Catherine Alice, whose father the Reverend George Pearse was Vicar of Martham at that time.

Here is the inscription translation:

“To the Glory of the Lord, the best, the greatest and in memory of a very loving husband the Reverend Gentleman Jonathon Dawson, Master of Arts from Exeter College one of the Oxford Colleges who died on the 29th day of January 1855 aged 34 years at Rollesby and near this place facing east outside the walls lies buried. By Catherine Alice Dawson his wife this sanctuary was built and the whole church restored. In the 1855th year of salvation the work was begun. In the year 1861 it was finished.”

Also in the Easter Sepulchre you will find the coat of arms of the Dawson and Pearse family as follows: Arg., a chevron gules between, in chief three martlets and in the base a cross moline sable, Dawson: impaling. Vert, a bend cotised or, Pearse. Crest, a nag’s head couped fretty. To the memory of the Rev. Johnathan Dawson, A.M.

(The busts of the Rev Jonathan Dawson and his wife by Holme Cardwell are not part of the original design but have been placed there in more recent times. Subsequently, Catherine Dawson married again and became Mrs Longley).

The iron work chancel screen was also made by Hardman & Co.

Angels on the Chancel Arch

The angels each side of the chancel arch hold a chalice and paten.

Angels on the Chancel Roof

Beginning by the chancel arch you see on the north side:

An angel swinging a censor.

An angel with a shawm.

An angel playing a lute.

An angel blowing a ram’s horn.

On the south side is:

An angel swinging a censor.

An angel holding a viol.

An angel playing an accordion.

The Bells:

| Bell | Founder | Date | Weight |

| Treble | John Stephens, Norwich | 1717 | 5cwt,1qtr, 18lbs |

| 2 | John Stephens, Norwich | 1717 | 6cwt,2qtr, 14lbs |

| 3 | A & W Brend, Norwich | 1611 | 7cwt,2qtr, 20lbs |

| 4 | R Brasyer, Norwich | C15th | 8cwt, 3qtr, 8lbs |

| 5 | Meers & Stainbank, London | 1862 | 10cwt,1qtr, 2lbs |

| Tenor | R Brasyer, Norwich | C15th | 12cwt, 2qtr, 8lbs |

In 1552 there were four bells of 8cwt, 12cwt, 15cwt & 20cwt.

NB. The 15cwt tenor (listed above) was probably recast in 1717 and sacrificed to create the new treble & second bells, bringing a ring of five bells up to a ring of six.

In recent times the bells had stood silent for over 70 years due to an unsafe wooden bell-frame in the upper belfry. Early in the 1990s a decision was made to have the bells removed from the old frame, restored and retuned and refitted in a new frame lower down in the tower beneath the old frame (the old wooden frame remains in situ in the upper belfry).

The current treble and 3rd bells were repaired by welding at Soundweld, Newmarket, Suffolk, before all six bells were tuned and equipped with all new ringing fittings for re-hanging in a new fabricated steel frame during 2000 by Tony Baines. A small local team of dedicated bell-ringers now ensure that the sound of the bells once again rings out for Sunday morning services and also weddings and if required, funerals.

In the Churchyard, close to the north-east corner of the chancel are the graves of Anna and David Hinderer who were pioneering C.M.S. missionaries in West Africa in the mid-nineteenth century, founding the Christian church at Ibadan in what is now Nigeria. Anna died at Martham in 1870 whilst her husband was serving as an assistant curate here.

Not far from the south-east corner of the chancel you will find the grave of John Page who was foreman of the bricklayers during the nineteenth century restoration.

Many of the other graves have splendid headstones with interesting carvings of ships on those who were seafarers. In the centre of the southern part of the churchyard is the Millennium yew tree.

Who built the original round tower church?

The early local Anglo Saxon Christian community would probably have had a primitive church of some sort and the foundations of a former stone built round tower were identified during building work to the tower footings in 1999. These pre-dated the present building. Domesday (1086) also says that Martham had a round tower church. Such a structure could only have been built by a family wealthy and influential enough to carry out this major project.

The Gunton family had a considerable presence in Martham from the 12th to the 14th century. You can read more about the actual family HERE.

In about 1160 the Gunton Manor in Martham was at what we now know as Moregrove and it included St Mary the Virgin. In 1160 Roger De Gunton gave the church and all its appurtenances to the Priory and Convent of Norwich for the redemption of his soul.(20). It was not unusual for landowners in the 12th century to grant their churches to ecclesiastical institutions, both as a pious act and in the expectation of prayers being said for the redemption of their souls. Roger de Gunton made this gift and Adam de Walsingham was appointed as the Vicar.

In 1224 Matthew de Gunton, a descendant of Roger de Gunton above, held possession of the manor of Moregrove although it was not called by that name at the time. As lord of the manor of Moregrove Matthew had the right to appoint rectors (called an advowson) but in 1224 he gave the right to the Monastery and Priory at Norwich Cathedral on the understanding that the monks would pray for his soul and the souls of his family and servants.(21) As a result of this gift the power to appoint vicars at St Mary the Virgin comes under the patronage of Norwich Cathedral and the Cathedral remains responsible to this day for appointing parish priests.

Matthew also gave the church 9 acres of land which was probably extremely near to it as much, much later the church gave land where the former first school was built and sold other glebe land in School Road for housing.

One of Matthew’s daughters was called Juliana and she married Simon Poche (Peche). At an unknown date Simon and Juliana were recorded as being benefactors of the Church at Martham.(1&2)

We don’t know the exact date, but probably before 1292, Roger de Gunton (1250 to 1323) the son of Matthew gave, by undated deed, to God and the church of the Holy Trinity of Norwich, a messuage (house) at Martham and 12 acres of adjoining arable land. Adam de Walsingham was made Vicar(9). It is likely that the house given by Roger de Gunton was the forerunner of the existing Rectory in Repps Road. This building and its nearby Rectory Farm once had a huge tithe barn nearby which was needed at the time to store the tithes mostly made up of cereal crops.(22)

So, the Priory had been given the church, a rectory and 21 acres of land by the Gunton family between 1160 and 1292. The above events prove they owned land in the village centred at Moregrove. They were well established at Gunton by the beginning of the 12th century, they had the wealth and were very well connected to the highest strata of East Anglian society. Importantly they demonstrated pious acts over many years across generations. To give land and buildings so generously to the Cathedral at Norwich must surely have meant they owned the land and built the round tower church or substantial improved a pre 10th century church. I believe the Gunton family are the only candidates for those that built the original round tower church.

Who Built the Church We See Today?

My thanks to Nicholas Andrew Trend, for his considerable help with the following information and for allowing me to use extracts from his essay “Wighton: the church, the village and its people, 1400-1500”

Excavations by the Norfolk Archaeological Unit took place in 1999 and revealed the foundations of an early round tower church, probably dating to the 12th century, preceding the existing church that we see today.

The round tower church was replaced with mostly what we see today in two subsequent periods. The first was from about 1370 to 1475 in the perpendicular style of that era. This included a chancel but that became totally dilapidated and was rebuilt between 1855 and 1861. The new chancel is a magnificent example of the gothic revival architecture of that period by the architect Philip Boyce.

These are known facts but identifying who built the 14th/15th century church has been a problem to date. The assumptions have always been based on architectural styles of the time but now in-depth research has clarified who built it.

The building of St Mary’s church must have been an expensive, complex undertaking requiring a great deal of planning, management and execution over a sustained period and yet we know almost nothing about it. Records about this large project are almost non existent and there is also a dearth of information about how it was paid for. This apparent lack of information is perhaps even more surprising when it is known that the fifteenth century saw a sustained wave of church reconstruction across Norfolk and yet hardly anything is known about who commissioned and managed the work and this is particularly true of St Mary’s at Martham. The dating evidence about the building of the church is almost entirely based on architectural evidence rather than ecclesiastical or manorial records. Antiquarians like Blomefield have recorded valuable information about some aspects of parish church histories but whilst these provide invaluable information, they were written several centuries after the actual events.

What we really need is a greater understanding of the medieval process for commissioning such large, expensive projects and written records of the hierarchy that existed within a cathedral priory to manage these undertakings. Presumably large building projects in medieval times were no different to now. A body at the top of the church would have taken strategic policy decisions on building projects including identifying the necessary funds. These decisions would inevitably been affected by politics and favouritism. What we do know is that by the 1280/90’s – half a century before the Black Death – a strong decline of church building set in nationally due to the poor economy of those times which lasted until the 1360s. The consequences of the Black Death included a great loss of not only labourers but clerics, scribes, architects and the professionals needed to manage large scale projects. A strong recovery began towards the end of the 14th century. It looks very much as if this resulted in a surge of new church building in the late 14th and first half of the 15th centuries as a sort of catch-up period although it was unequally spread.

I can find almost nothing about the hierarchical structure that supported these building projects and the ecclesiastical structure of a cathedral is not well suited to external projects as its key purpose is inward looking to manage its religious functions. The post of cellarer is sometimes quoted as being key to these projects because he was responsible for the provisions of daily life including food, wine, clothes, materials, furniture and payments of a host of tradesmen. In that role he was the chief means of communication between church and the outside world: he went to markets and fairs and bought a very wide range of provisions needed by the Cathedral. He may have been a lay-monk or lower ranked cannon. He was trusted to source, purchase and pay for provisions but it does not seem credible that he could authorise complete building projects without being subject to some sort of executive reporting.

This lack of management structure detail, contract agreements, payment schedules, architectural drawings, account rolls etc probably explains why we have fallen back on substantial architectural observations based on surviving buildings – not much else is available.

In some cases there is one source of information that supports church building or improvement projects and that is endowments. In medieval times it was not unusual for wealthy people to leave sums of money or even land to the church for the redemption of their soul. These are often recorded in account rolls or Wills. Sadly, in the case of Martham only two can be identified from this period. One contributor to the cost of the building was the local landowner Roger Clarke to whom a stained-glass window was dedicated but it disappeared during the subsequent re-building of the chancel. Another was from the then vicar, John Spire, who left 10 marks (£6 13s 4d or £6.66) in 1375 to the Church. Nether of these generous gifts were substantial in comparison to the total costs of re-building.

Perversely the excellent records that do exist in the form of Domesday and the Stowe Survey of 1272 show that Martham was populated by a very high number of free, small land-holders who were unlikely to be able to afford big donations to the church. The Prior held the main manor and another, Moregrove, of about 130 acres was held by an absent owner with little allegiance to the village other than as an income source. Records of the Cathedral Priory of the Holy Trinity, Norwich do at least confirm that Martham belonged to it at the time of the Stowe Survey, in 1292.

It is against this somewhat daunting background that, in the case of St Mary’s, we have to search around for scraps if information that may help identify how it was that Martham was provided with the magnificent church we see today. The architectural evidence says it was built between 1377 and 1450. Supporting this we have some facts and some comparative data as follows.

The cellarer’s rolls of the then Prior of Norwich (subsequently the Dean and Chapter) suggest that construction of the chancel at Martham started in 1456 and wasn’t completed until 1469 and the rolls say it cost £66 13s 4d (100 marks) to build the chancel from 1456 to 1469 (3). The chancel was by Robert Everard who was also the master mason and architect of Norwich Cathedral’s spire (4). Records also show that similar chancel improvements were undertaken by the Prior at Alderby in 1458-59; at Hempstead between 1470-1475 and at Worstead between 1484-1488. So, the Martham work was in-line with that carried out elsewhere at the time.

The cellarers Rolls of the Norwich Cathedral Priory record payments of £13 6s 8d in 1456-57 and 1458-59 to Everard as part of the 100 marks contract price; a second contract of £11 6s 8d is referred to in 1468-69 when a part payment of £4 13s 4d was recorded (8). In 1468-69 a sum of 18s 10½d was paid to a plumber working on the chancel and in the same year Thomas Glasswright received £7 in full payment for four new glass windows There are also records of Thomas repairing windows in the cathedral from 1431 to 1477 (7).

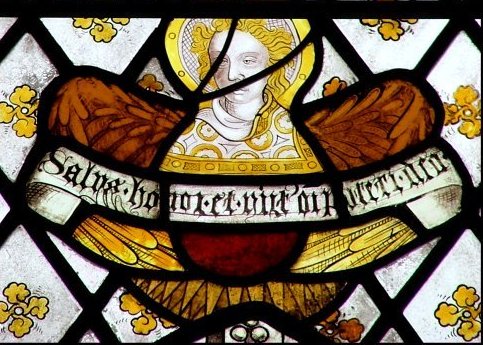

C Woodford in his Ancient Glass in Norfolk, typescript notes, c.1935–50 talks about the relationship between a group of female saints in the stained glass tracery lights at Martham, Cley, Field Dalling, Pulham St Mary and Wighton, as being “allied in subject-matter as well as in style”. The impression left is that they were the work of the same glazier.

An inscription in a south chancel window, recorded by Norris, read “Orate p aia …thowe…norvici cellarii”, a clear reference to Richard Salthouse who was the cellarer at the Priory from 1465-1472 (6). Richard Salthouse commissioned stained glass angels bearing scrolls at St Mary’s chancel in 1468/69. Similar angels exist at All Saints, Wighton which were commissioned earlier in 1455-/56 but bear the same inscription “Salus, honor et virtus omnipotenti Deo” (Salvation, honour and power be to almighty God). It seems the Prior cellarers used the same source for both churches. The angel scrolls are shown below.

At Martham payment for glazing the chancel came in the same year (1468-69) that a plumber was working on the roof. Presumably he was applying the final waterproof leading. The glazing and plumbing work was known to have been commissioned by the same cellarer – Richard Salthouse (8).

The nave at Martham has distinctive and unusual s-shaped shouldered mouldings (ogees) at the heads of the main windows that are only found in the nave windows at Wiveton (c.1437), Great Cressingham (before 1440), Wighton (1440s), Norwich Blackfriars (before 1449), St John Maddermarket (1420 – 1452) and at South Creake (before 1451). Again, this looks as if it was provided by the same stone mason and centrally commissioned. The records of the Priory and Monastery at Norwich Cathedral reveal that their master mason Robert Everard was working on St Mary’s chancel during the years 1450 to 1475.

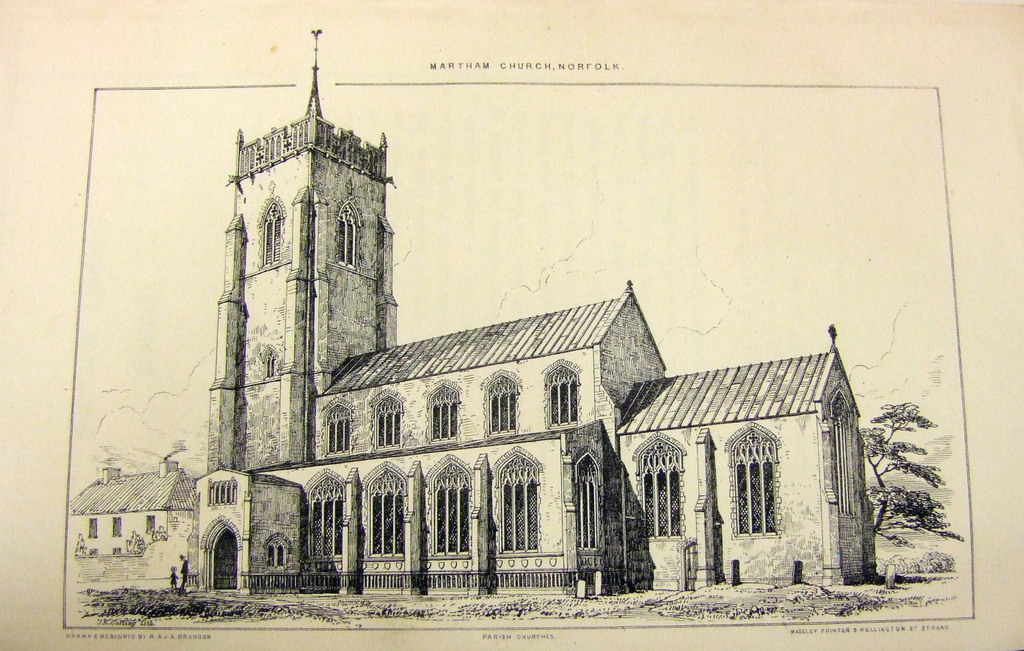

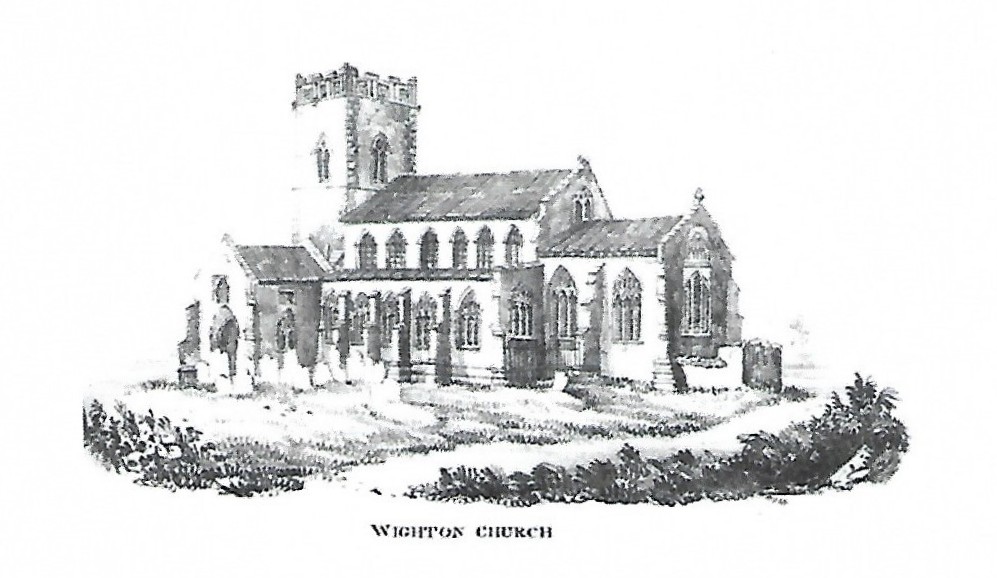

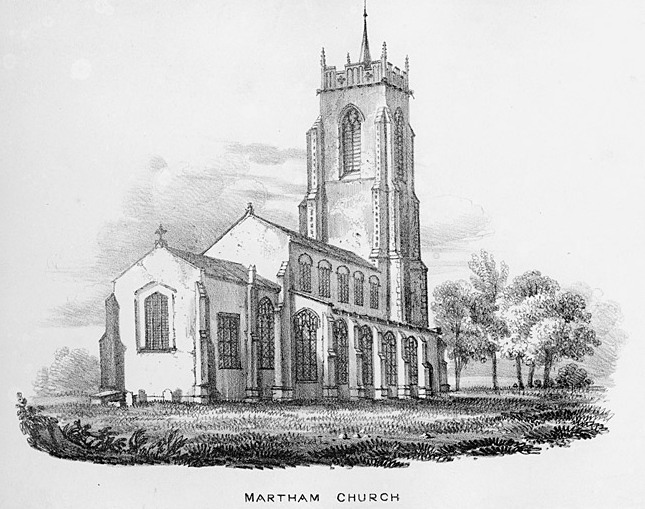

Several comparisons have been made between St Mary’s, Martham and All Saints, Wighton because they were both built during the same period and share Norwich Priory commissioning as well as architectural similarities. Here are two comparison historical sketches of the churches:

In summary we can see that the Norwich Cathedral Priory commissioned similar projects at various levels that are common to several churches across East Anglia and there are distinct similarities between St Mary’s at Martham and All Saints, Wighton. So, it is reasonable to come to the conclusion that the only organisation with sufficient money and organisational ability to build the 14th/15th century church at Martham was the Norwich Cathedral Priory.

The Present Chancel

In his book “Manuscript Collections relating to the County of Norfolk” which was published in 1853 William Tilney Spurdens (10) described the sad state the church had fallen into as follows:

“This fine Church is a Perpendicular Structure, of great magnificence but now much neglected. The tower is of noble proportions, with a rich embattled parapet and excellent base mouldings worked in flint and stone which continue round the body of the church, the Chancel being left singularly plain. The absence of parapets is a peculiar feature in the Norfolk Churches and stamps them, as in this case, with a remarkable character, the thin line of overlapping lead sharply defining the junction of the roof with the walls. The south door has been a beautiful piece of woodwork exquisitely carved, with a very good closing ring and key plate, it is now sadly mutilated; most of the old benches remain, without backs and with very well executed finials. The ascent to the rood loft is on the north side, and a post-reformation roodscreen with doors, locks opened with this key, ![]() separates the Chancel from the nave. Considerable portions of the old stained glass are scattered throughout the different windows of the Church.

separates the Chancel from the nave. Considerable portions of the old stained glass are scattered throughout the different windows of the Church.

There is a fine hammer-beam roof over the nave, of the same date as the rest of the Church; it is in a very dangerous state, and unless immediately attended to must shortly fall. It is lamentable to think how many of these noble roofs, which with common attention would yet last many centuries, are being lost by the neglect of those whose duty it is to repair and hand down to posterity the Churches which their more pious ancestors so liberally bequeathed to them.

The church affords accommodation for about 470 worshippers.”

It is not surprising that against this background a new chancel was built between 1855-61 to totally replace the mid 15th century original. The new chapel is similar to the finest of chancels to be found in medieval churches before the Reformation. The architect who was commissioned to carry out the work was Philip Boyce of Cheltenham whose brilliant design was accepted for display at The Royal Academy Exhibition of 1856. The decorative carving including the pulpit – shown left – was done by the sculptor Henry Earp (brother of the more famous Thomas) and also the young Benjamin Grassby.

You can read a fascinating account here of what St Mary’s was like before its restoration in 1856. The article was written by the Rev. Edward Samuel TAYLOR (1826-1863), who was a curate at the church in 1851 before he moved to Ormesby St. Margaret.

(Source: Taylor, E. S. (2020). Notices of the church of Martham, Norfolk, previous to its restoration in 1856. Norfolk Archaeology, 5 (1), 168–179. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. International Licence).

On the north wall is an Easter Sepulchre and on its back wall is a dedicatory inscription to the Reverend Jonathan Dawson (1821-1855), in whose memory the complete restoration was carried out, and paid for at a staggering cost of £8,000, by his widow Catherine Alice (1827-1916), whose father was the Reverend George Pearse (1793-1882) who was Vicar of St Mary’s from 1834 to 1876. The buying power of £8,000 in 1855 would today (2020) require the equivalent of £602,362 (13).

Sources:

(1) ‘An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk’ by Francis Blomefield.

(2) http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=78420.

(3) NRO DCN 1/2/61, DCN 1/2/66 and DCN 1/2/67).

(4) www.heritage.nofolk.gov.uk

(5) ‘Medieval Flegg’ by Barbara Cornford.

(6) Cellarer’s Rolls of Norwich Cathedral Priory.

(7) David King, 2006, page 139.

(8) NARG News No33, June 1983.

(9) In the Domesday Book Martham was held by the King, Count Alan, the Bishop of Thetford and St Benet’s Abbey. The Bishop of Thetford’s holding was the most valuable and included a church with 50 acres of land. The present St Mary’s dates mainly to the 14th and 15th centuries. The 15th century chancel was built by Robert Everard, the architect of Norwich Cathedral’s spire. An archaeological watching brief was carried out by the NAU in 1999 during the lowering of the floor in the west tower revealed the foundations of a round tower, probably dating to the 12th century, probable medieval graves and a small lead-melting pit containing medieval window glass.

(10) William Tylney Spurdens was headmaster of Paston 1807-25 and assistant curate of North Walsham 1814, Felmingham and Antingham 1815, Dilham & Honing 1826-36, Worstead 1837-40.

(11) James Woodforde (1740–1803) was an English clergyman, known as the author of The Diary of a Country Parson. This vivid account of parish life remained unpublished until the 20th century.(12) Joshua Arthur Brandon (9 February 1822, London – 11 December 1847, was an English architect and author. Prior to an early death aged twenty-five, his architectural practice (particularly in church architecture) was promising and growing. In 1848 his “Parish Churches” publication featured 63 churches from across England, each with perspective views, a short description in text and a plan to the same scale for all the churches.

(13) Personal Finance UK Information Website Guide by Money Sorter UK.

(14) John Berney Ladbrooke, Robert Ladbrooke’s third son, was born in 1803. He became a pupil of John Crome, who was his uncle by marriage, and whose manner he followed. John Berney Ladbrooke excelled in the representation of woodland scenery. He exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1821 and 1822, and frequently at the British Institution and the Suffolk Street Gallery up to 1873. He died at Mousehold, Norwich, on 11 July 1879.

(20) Blomefield’s original entry reads: “The Church is dedicated to St. Mary and was a rectory, valued at 37 marks, and given by Roger de Gunton with all its appurtenances, with the consent of Nicholas his son and heir, in the presence of William de Turbeville Bishop of Norwich for the redemption of his soul, to the prior and convent of Norwich. Witnesses, Abbot Danyel (of Holm), William and Roger archdeacons, William de Hasting, Alan de Bellofago, and this was about the year 1160 and was confirmed by the aforesaid Bishop.”

Witnesses to this transaction included Abbot Danyel (of Holm), William and Roger who were archdeacons, William de Hasting and Alan de Bellofaga. They all held high ranking positions in the church or crown. Abbot Danyel (Daniel) was the Abbot of St Benet’s Abbey in about 1151 and he died in 1168. William De Hastings lived from 1165 to 1225 and died at Swaffham and at one time was a steward to Henry II. Alan de Bellofago was also known as Beaufoe and was believed to be related to Bishop William Beafoe in the mid 1100’s. William & Roger were archdeacons of the Norwich Priory in around 1168(5). The witnesses were all alive in 1160 which supports the date of the gift of the church by Roger De Gunton and indicates the influential levels he moved in.

(21)Blomefield’s original entry reads(1): Matthew de Gunton, granted by fine in the 8th of Henry III. to William, prior of Norwich, the advowson of the church of Martham; who received Matthew, and all his men, or tenants to be partioners in all the prayers of their convent; and in the following year, he also gave 9 acres of land here to master Adam de Wausingham, and his successors, in the church of St. Mary, of Martham, Adam paying to him 40s per annum.

(22) Blomefield’s original entry reads(1): Roger de Gunton, probably son of Matthew, gave by deed sans date, to God and the church of the Holy Trinity of Norwich, a messuage here, and 12 acres of arable land adjoining, late Mr. Adam de Wausingham’s, free from all services, for the life of Isabell de Castre his mother-in-law, and after her decease, to the priory, paying to him and his successors 2s. per annum.—witnesses, Reyner de Burgo, William de Stalham, Knts. Robert de Mauteby, &c.

Photo Gallery

Below is an album of photos relating to the church. Click a thumbnail for a close-up and scroll through all the images from there.