Wherrymen of Martham

The River Thurne flows slowly across the north of Martham providing a network of links from West Somerton to the east, Potter Heigham to the west and then via Womack Water to Ludham or the River Bure at Thurne where another junction takes you west to Wroxham, Hoveton, Coltishall and at one time even reached Aylsham. Alternatively going south from the Thurne junction you could meander your way via Acle to Great Yarmouth. It is then possible to cross Breydon Water to Norwich via the River Yare or to Beccles and Ditchingham using the River Waveney. This then was the river highway that Norfolk wherries thrived on during the 18th/19th century.

There were three staithes (or landing points) on the River Thurne at Martham. Two were fed by lanes at the north end of Common Road and Ferrygate and the other, near Dungeon Corner, by a green lane leading to Damgate. In the 1800’s these would have been busy with wherries loading and unloading their cargo. Many of these were owned or manned by Martham men.

The wherry was once a traditional part of the Norfolk scene and its origins go back much further than operators can be traced from Martham. For centuries roads were poor and water was the principal means of transporting heavy or bulk goods. It is generally accepted that the forerunner of the wherry was a square-rigged clinker- built keel boat dating back to the early 1500’s. The disadvantage of the keel boat was the deeper draft and the style of rigging which made them difficult to sail close to the wind on the narrow rivers of the Broads. The design evolved into ferry boats first seen on the Thames and used as ‘water-taxis’ more than for cargo. Wherries proved to be faster than keel boats, and speed mattered, consequently the Norfolk wherry became the commercial working river ‘juggernaut’ of the 18th/19th centuries.

In 1798 there were 120 wherries registered in Norfolk and the average tonnage was then 30 tons. As the years progressed there was an increased demand for woollen goods as well as growth in the agricultural trade. Bricks were made at Martham and river transportation was vital. The docks at Great Yarmouth were pivotal for moving goods like grain in and flour out, malt, beer, reeds, coal, sugar, tobacco, cattle feed, fertilizer, cement, chalk, timber and even refuse. There were many brickfields in Martham and one wherry was named ‘The Martham Trader’ or ‘Brick Hod’ because of the trade in Martham red bricks.

Wherries were constructed at small yards without plans following family traditions; they just worked out the designs as they went along. In the 1880’s a 30-ton wherry cost £400 to build so to own a wherry was quite an investment. Merchants would often have their own wherries and employ a crew, but many others were privately owned and families would live on them. Those employed on wherries were mostly called watermen or boatmen whilst owners were called wherry owners.

Wherry Life

It seems that wherrymen were quite a breed. They were hard-living, hard-drinking, hard-bitten men. A love of alcohol seems to have been common throughout the wherry fraternity. Wherrymen often dressed in distinctive sealskin caps or bowler hats and in winter they wore leather crutch-boots. A wherryman often lived aboard the boat with his wife and family. It was a cramped life, with virtually no personal space and consisted of just two bunks and a few lockers plus a small stove so food preparation and cooking must have been difficult. They had to work hard in all weathers, so it was a tough life. It was a dangerous place to raise children and accidents and even fatalities were not uncommon. As time went on some wherrymen acquired or rented small marshland cottages for their families. Safety regulations did not exist and wherries were often piled dangerously high. It was hazardous work for a single person so if the family lived on dry land a workmate was needed. Considering the responsibilities and skills needed employed men were not overpaid for their work although they earned more that agricultural labourers. They were often treated with a degree of suspicion based on reputation and rumours of smuggling, pilfering, carriage of illicit goods or boats used for illegal sports like cockfighting. The essence of a wherryman’s trade was the need to acquire a consignment ahead of their rivals, deliver it as fast as possible and then turn the wherry around with a fresh load. Self reliance and a sense of comradeship were evident, together with a pride in their vessels.

Warnes Family, wherrymen

Whilst several local men and families worked on wherries the best known from Martham are probably the Warnes family whose distant ancestors still live in the village to this day.

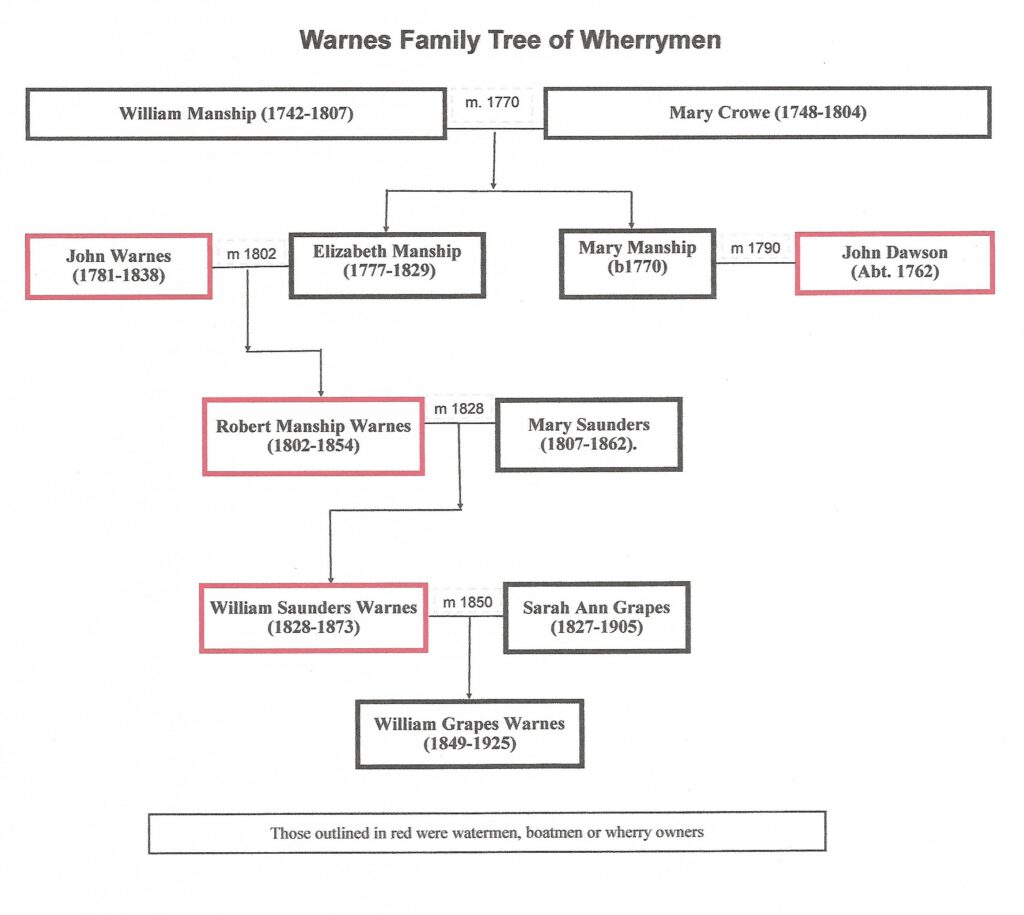

Several generations of parts of the Warnes family were associated with working on wherries and it may be easier to follow them using the family tree shown below. It only shows those members of the family that were more directly involved with work on wherries.

John Warnes (1781-1838) was born at East Somerton and was a boatman. He married Elizabeth Manship (1777-1829) at West Somerton in 1802. Elizabeth had a sister called Mary, born 1770, and she was also married to a waterman called John Dawson.

John Warnes & Elizabeth had a son named Robert Manship Warnes (1802-1854). In 1841 he lived with his wife Mary, nee Saunders, at Black Street, Martham; they had married at St Mary’s in the village on 16th July 1828 and went on to have six children. In 1841 Robert was a waterman but by 1851 he had become one of an exclusive group of men as a wherry owner and in that year only four men in Norfolk described themselves as owners of wherries. Many coal, timber and grain merchants would have owned wherries, but their ownership would have been secondary to the prime description of their occupation. For them, a wherry would have a been an asset of the business just as a delivery lorry is today.

One of the six children of Robert & Mary was William Saunders Warnes (1828-1873) who was destined to have a colourful life. Even as a young lad of 13 he would probably have been working with his father on the wherries as it was customary for lads to assist on the boats from a very young age. He married Sarah Ann Grapes at St Nicholas Church, Great Yarmouth on 22nd January 1850. Sarah was from a family that were associated with riverside pubs at The Lion, Thurne and the Berney Arms on the River Yare. Pubs were an integral part of a wherryman’s life providing an evening stopping point and leisure spots. Many watermen had a reputation for hard drinking.

When William & Sarah married their address was given as North Quay, Great Yarmouth. The port was where the three rivers, the Yare, the Waveney and the Bure converged and many wherries would be moored there. William had become the master of the wherry “Victoria” which probably belonged to his father Robert. William was then only 22 and had a crew to assist him. After their marriage William & Sarah only had a couple of months together before a turning point in their lives. Events moved fast when William was charged on 23rd March 1850 with ‘feloniously stealing two sacks each of the value of three shillings, and four bushels of malt, each of the value of five shillings of the goods and chattels of Richard Bullard. Then and there being in a certain barge or wherry called the ‘Jane’ upon the navigable river Yare’. He was accused with two accomplices called Thomas Saunders, aged 22, and Thomas Paston, aged 21, who were members of his crew. All three were remanded to appear at the Great Yarmouth Quarter Session on 27th June 1850 before the local Recorder. The trial papers describe in detail the proceedings in court, mostly based on evidence given by a policeman who had seen William transferring sacks from the ‘Jane’ to the ’Victoria’ that were moored adjacent to each other. Sacks were produced in court that were marked ‘Ballard’ and ‘Ballard-Malts’ that had been found with others aboard the ‘Jane’. All three men were found guilty and William was given twelve months goal with hard labour for being the ringleader whilst Thomas Saunders and Paston were given nine months goal with hard labour. Sentencing policy was much harsher in the mid nineteenth century than it would be now and concentrated on setting an example to deter other would be criminals from offending.

The men served their time at the Tolhouse goal where the oak-lined cells are cold and dark with stone floors. The prison regime was severe and included a large treadmill that served no practical purpose except for punishment exercise. Men worked for 15 minutes, rested for 15 minutes and then returned to the treadmill and this routine lasted for up to 8 or 9 hours a day. The treadmill looked like a rather large stairway where prisoners were condemned to everlasting climbing never to reach the top.

William was fortunate that his father owned at least one wherry, probably two, and he had work waiting for him when he got out. His wife Sarah Ann was not so lucky, when William went to goal, she had a baby to look after and in 1851 she had returned to live with her elderly father at Potter Heigham whilst William served his time. Upon his release Thomas Saunders (no relation to William) continued to work as a waterman and lived with his wife and children at Gorleston. Thomas Paston left the river life and turned to farm labouring.

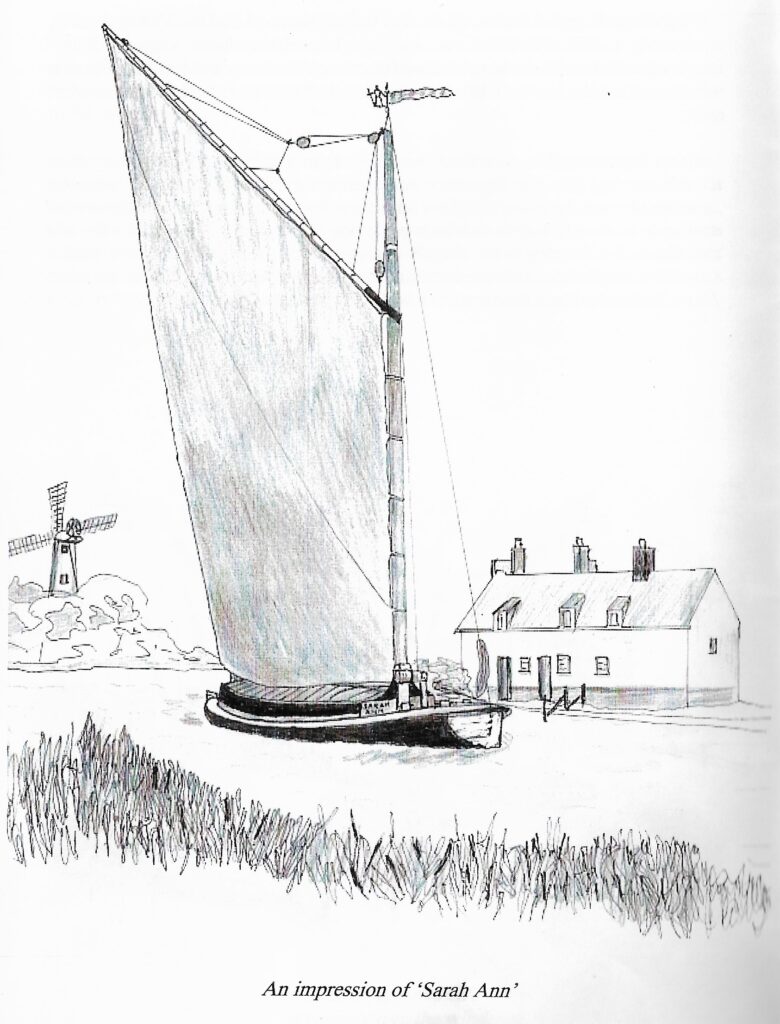

The hard life of a wherryman had its lighter moments. Regattas developed as regular sporting events and racing between trading wherries took place. Owners would sometimes race themselves or employ professional waterman for the prestige of winning. William won a wherry race at Wroxham in 1859 in the family wherry ‘Sarah Ann’, a vessel obviously named after his wife. His reward for winning was five guineas.

William continued to work on the rivers but by 1873 was said by members of his family to have become a heavy drinker and this caused problems for his wife and son William Grapes Warnes. William’s colourful life came to an untimely end when on 27th February 1873 he was found drowned in a drainage ditch. The cause of his death was recorded as “drowning and suffocation accidentally caused by the deceased falling into a dyke or stream of water.” He was recorded as being a wherryman. Perhaps the demon drink contributed to his demise. His son William had moved away to the north of England on account of his father’s volatile nature but later returned and lived in Lowestoft where became a bricklayer.

Other Local Wherrymen

The itinerant nature of being a wherryman means it is sometimes difficult to trace those who lived on the boats they owned or worked on. Nevertheless, the closeness of Martham to the River Thurne meant that some men who worked on the river also had homes and families on dry land. These are some drawn from the Martham census returns:

- Thomas Browne, who was born at Martham in 1778. He married Rebecca Fairweather (1783-1817) at St Mary’s on 23rd December 1804 and they had nine known children. In 1841 he lived at Damgate and was a boatman and a widower.

- Clement Cook was a waterman and lived at Damgate in 1841 with four of his children. He was a widower and only lived there for a short while. He was originally from Horning so may have plied his trade between the two villages.

- Robert Harris was originally from Repps but lived with his wife Mary, nee Bessy, at Mustard Hyrn, Cess, Martham in 1861 where he was a waterman. (Mary was the sister of Elizabeth Bessy the wife of John Nichols – see below. It is possible that Robert and John worked on the same wherry as each other). One of Robert & Mary’s sons, called John Benjamin Harris (born 1842), also become a waterman/boatman. He married Annis Dove in 1871. They lived at Black Street and Mustard Hyrn and John stayed in the same trade all his life until he died at Mustard Hyrn in 1907.

- James Harman Futter came from a lowly background being born illegitimate in about 1818. He sometimes used the surname Harman after his mother married Henry Harman in 1820. James married Elizabeth, nee Dove (sometimes recorded as Dowe) at St Mary the Virgin, Martham on 27th February 1840 and for the rest of their lives they lived at Damgate Corner, Martham where he started out as a waterman but progressed to become a wherry owner by 1863. His business must have been thriving because by 1879 he was a coal merchant which was most likely his principal occupation but he would still have owned the wherry and it would have been used as transport for the coal. All the couple’s eight children went under the surname Futter. One was called Paul and he was a wherryman in 1871 and 1881 probably assisting his father. Another son, called John, was a coal merchant and boatman at Upton with Fishley in 1891. Two other sons, Henry & James also became coal merchants. James senior eventually made good and lived until he was 73 whilst Elizabeth died in 1904 at the same age. They are buried together at St Mary the Virgin, Martham in the grave shown below.

- Louis Hewitt was born in Repps in 1867 and once he left school started work as a waterman. He married Selina, nee Bishop, at Martham in 1888 and they lived at Clarkes Farm, Ferrygate in 1891 where he was a waterman on a barge. Ten years later, in 1901, he had left the wherry trade and was working on a farm.

- John Nichols was born in Repps in about 1803 and married Elizabeth Bessy there in 1832 but for over 30 years they lived at Black Street and The Green in Martham where he was a boatman and a merchant. He must have been doing quite well because in 1861 they had a servant called Carolyn Payne from Martham. (Elizabeth was the sister of Mary Bessy the wife of Robert Harris – see above. It is possible that John and Robert worked on the same wherry as each other).

- Walter Scarlett (1818-1895) was living with, and worked with, Robert Manship Warnes at Black Street in 1841. Walter married Ann Gedge from Hickling in 1844 and in 1851 they lived near the staithe in West Somerton before moving to Catfield. Walter was a waterman all his life.

By 1881 there were only two men listed as wherry owners, watermen or boatmen in the census for Martham. It is probably no coincidence that the railway opened in Martham in 1878 and the 1881 census lists quite a number of men doing a variety of jobs on the railway. Transportation of goods obviously moved from the rivers to the railway and must have dramatically reduced the prospects of watermen and wherry owners.

With thanks to, and in memory of, Margaret Dickson (1938-2008) and her book “A Family of Wherrymen”.