Farming in Martham, c1800, viewed through the eyes of Thomas Francis

This page is based on a talk I gave for Martham History Group on 17th September 2019. Viewed through the eyes of Thomas Francis, who lived and farmed in Martham all his adult life from around 1770 until his death in 1837, this account introduces us to farming during a period of agricultural change throughout England but specific to Martham.

This is based on interviews by Arthur Young with Mr Francis for his book “General View of the Agriculture of the County of Norfolk” written from about 1790 to 1802 and first published in 1804.

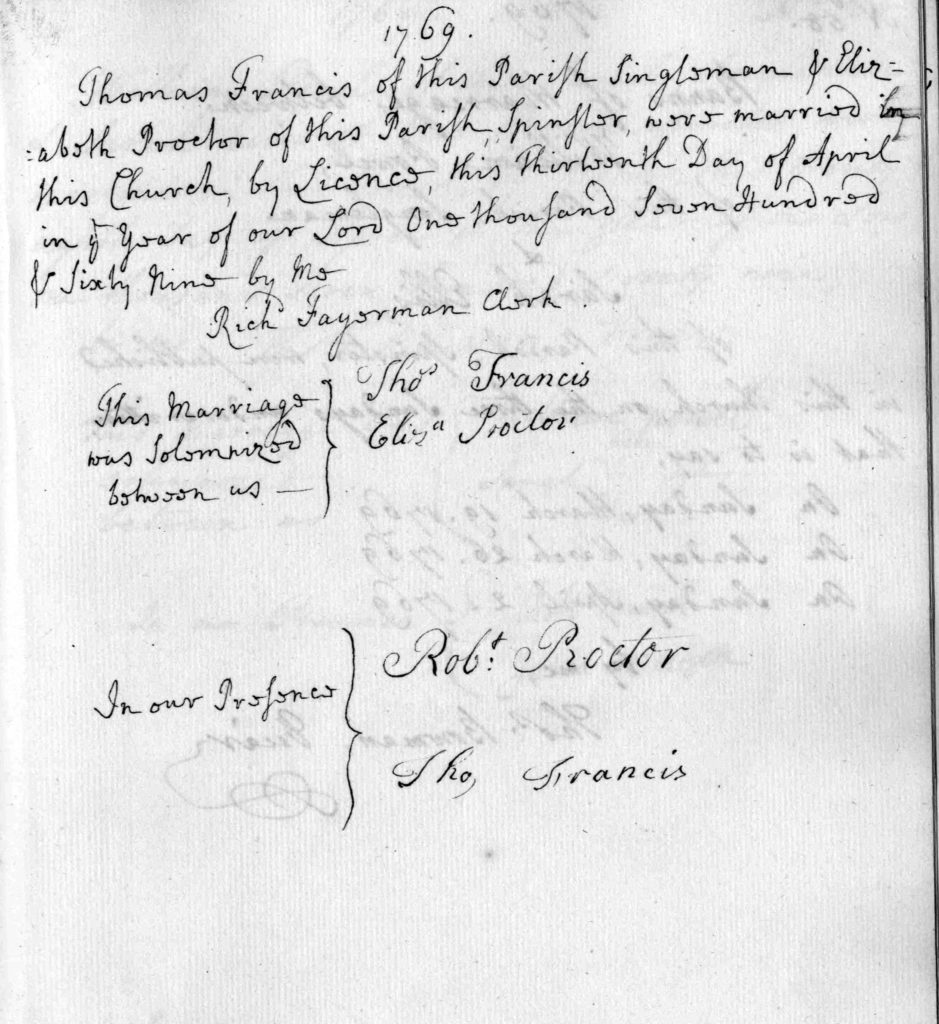

Born at Ingham in 1743, Thomas married Elizabeth Proctor on 13th April 1769 at St Mary’s, Martham. (See register entry on the left). Her father was the largest landowner in Martham at the time and lived at Martham Hall on Hall Road. One of Thomas’s sons married into the Rising family whilst other family marriages meant that Thomas became “well connected to all the great and good of Martham of those days”.

Thomas lived at West End Cottage which was where Grange Farm is today. His house was not the one we see today as it was built, or extended, in 1839 two years after his death. The house that was on the same site was known as West End Cottage when he was there. He did however have the red brick barns built next to the house in 1797.

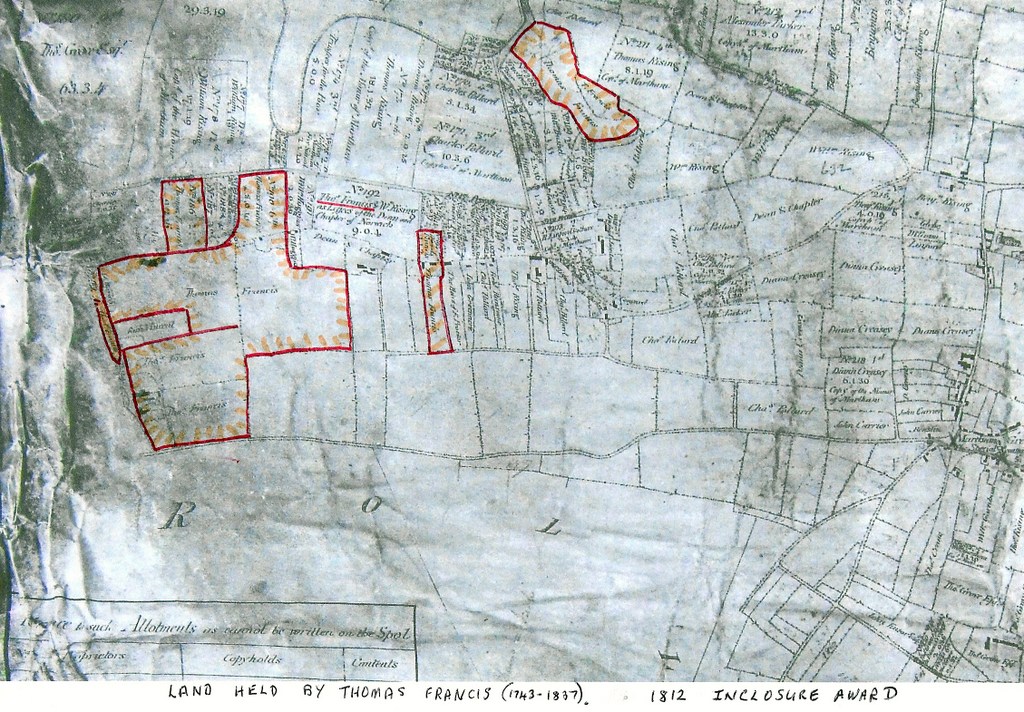

We can get an idea of the land farmed by Thomas from the 1812 Inclosure Award. It is a little later than the time we are talking about but would have been the same. The records show he owned about 90 acres of land in and around West End Cottage which was later re-named Grange Farm at Cess. He owned plot Nos: 167; 184; 186; 188; 189; 190 and 194 and also laid claim to some freehold land in the manor of Scratby. His harvest yields of 1800 show that he had at least 137 acres in crop so he must have rented land in addition to the 90 acres he owned.

Thomas outlived his two children and his wife and so in his Will he left his land holdings to his granddaughter Ann Rising Francis the daughter of his son Thomas Jnr. Much the same land can be seen as owned by Ann 30 years later in the 1842 Tithe Award for Martham. You can see how the land Thomas owned passed down to both his family and the ancestors of the Risings.

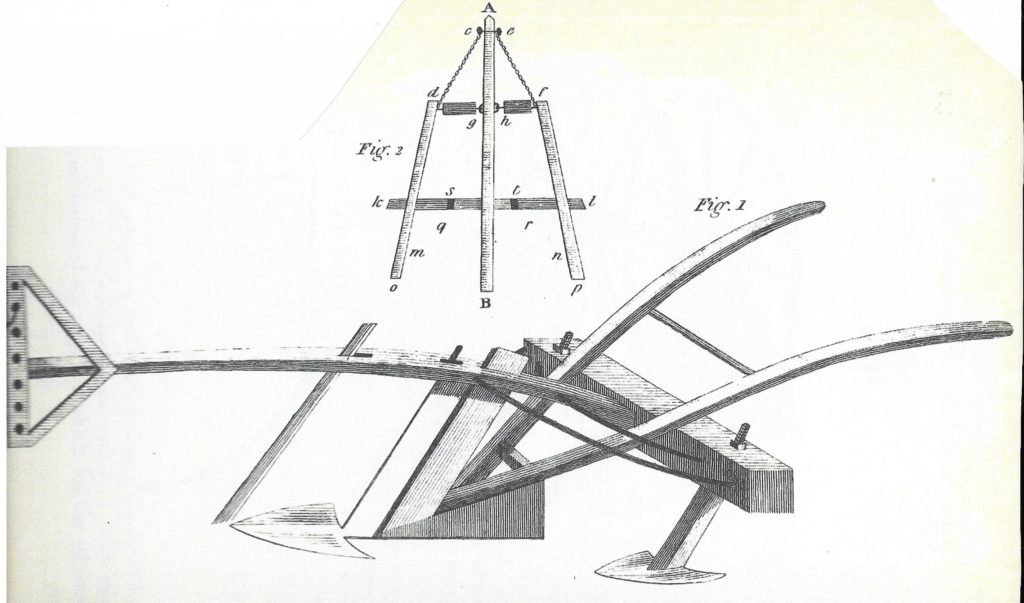

Thomas was highly regarded as a farmer by Arthur Young who quotes him frequently as a sort of role model of good practise. This is clearly illustrated when he quotes Thomas when talking about ploughs. It is apparent that Thomas had his ploughs specially made to his own design with a lower mounted beam which he found more efficient on the loamy soil so common in Flegg which did not need deep ploughing. He was familiar with this as he did much of the ploughing personally despite having labour available. Thomas ploughed to a depth of 4” to 5” and no greater depth was needed because the land was fine loams on a sandy bottom with some gravelly spots.

“The plough preferred by Mr Francis did not have beams mounted as high as is common in other parts of Norfolk. Mr Francis remarked “that the wheelwright made his based upon his own plan”; he ploughed much of his farm with his own hands and knows that when they are very flat the plough is apt not to cut a flat furrow, nor to go close to the heel, he therefore lowers the beam, and the share is two feet from the pain where the wheels touch the earth; and the beam ring being on the centre hole, the plough will then go alone without holding”

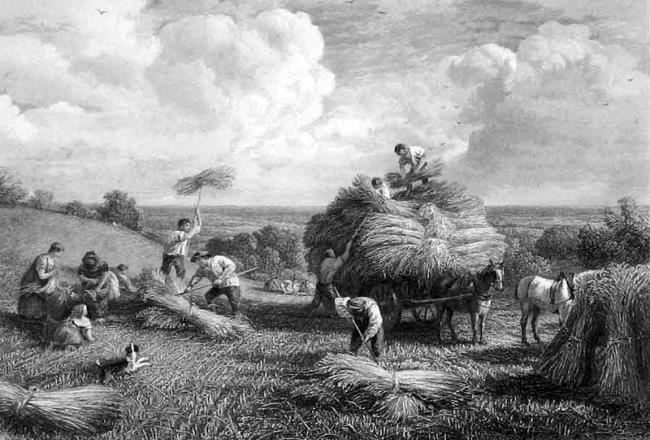

We don’t know how many farm hands he employed but 50 years later in 1851 his granddaughter (Anne Rising Francis) employed 20 labourers on her 250 acres so it is likely that Thomas employed 10 to 15 men and perhaps some boys, as was normal at the time.

Farming changed considerably during his time. In the mid 1750’s the country mostly existed on what it could grow. There were almost no food imports. From 1700 to 1800 the population of Britain roughly doubled to over 9 million and as a result there was great pressure to farm more efficiently. Rather than leaving fields fallow the use of the five-rotation system of husbandry became common in Flegg and Thomas used that consisting of (1)turnips; (2)barely; (3)clover (or other seeds); (4)wheat; and (5)peas (or oats).

Turnips can be grown in winter and are deep-rooted, allowing them to gather minerals unavailable to shallow-rooted crops. Clover converts nitrogen from the atmosphere into a form of fertiliser. This rotation resulted in intensive arable cultivation of light soils, it fertilised the soil and provided fodder to support increased livestock numbers whose manure added further to soil fertility. So, turnips restored the soil’s fertility and when they were harvested the turnips could be stored to provide food for livestock over the winter.

After a few years Thomas found yields of turnips fell and by 1802 had to double the amount of seed used to get the same returns. He and his neighbours also found the land got sick of clover and he substituted peas and he also occasionally sowed turnips after wheat. He also grew oats although they were not a favourite crop of his and he found barley a more reliable crop.

Thomas also sowed Buck Wheat. Often after turnips which helped give good yields. Buck wheat is an Asian plant of the dock family, it produces starchy seeds that are used for fodder and also could be milled into flour. It just goes to show how little things have changed or perhaps gone full circle as it is now something sold in stores like Waitrose as a healthy food option providing the following benefits: –

- Improved Heart Health. …

- Reduced Blood Sugar. …

- Gluten Free and Non-Allergenic. …

- Rich in Dietary Fiber. …

- Protects Against Cancer. …

- Source of Vegetarian Protein.

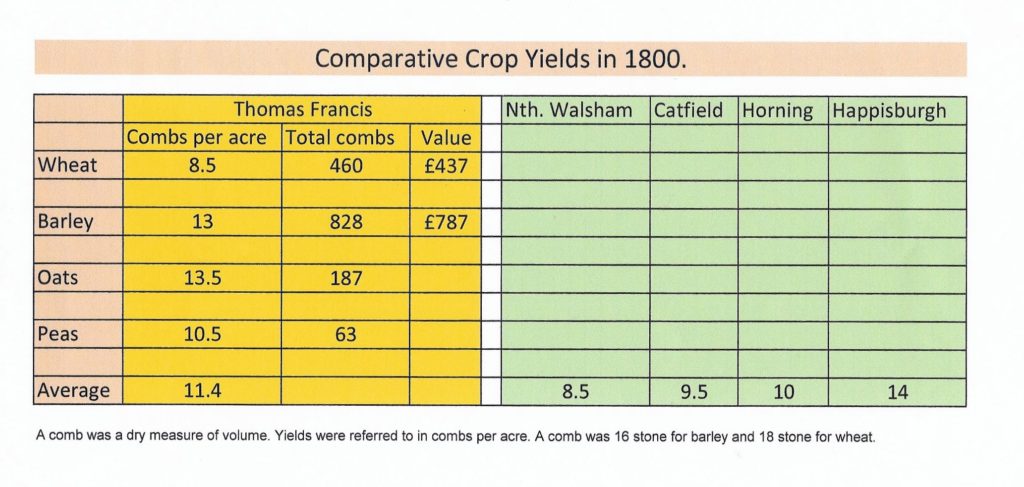

All in all, Thomas must have been an efficient farmer as his husbandry yielded higher than average returns in comparison with most neighbouring districts. The chart below shows his actual yields in 1800.

The chart shows an average yield of 11.5 combs per acre which combined with the high sale price for the year (1800) gave a good farming year.

By comparison other local results were: – North Walsham 8.5 combs per acre. Catfield and Happing 9.5 combs per acre. Honing 10 combs per acre. Happisborough and Walcott 14 combs per acre.

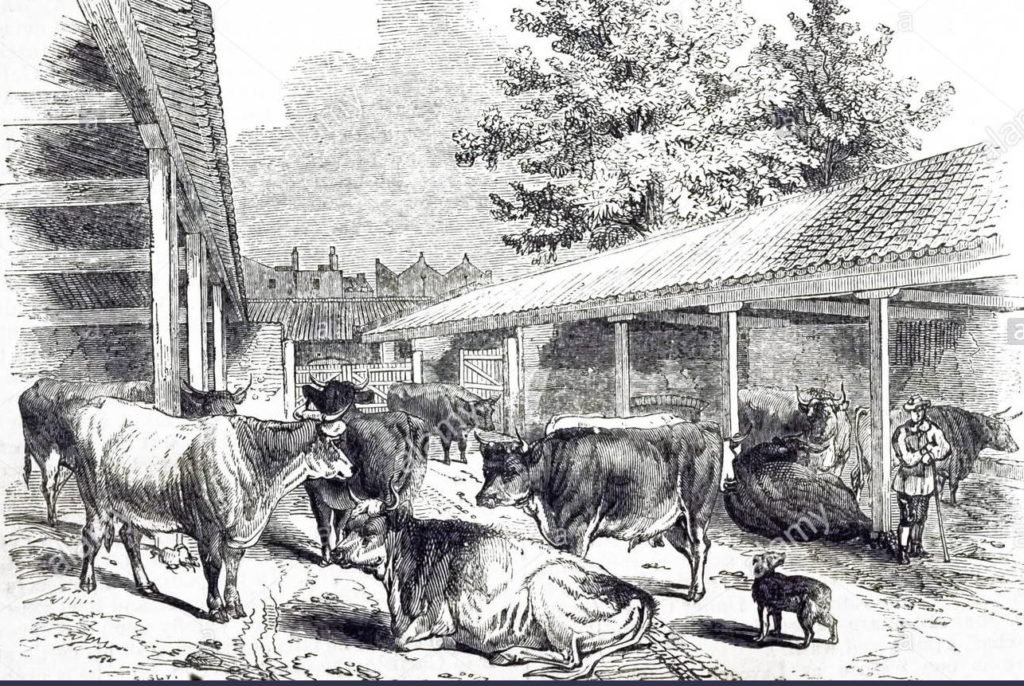

Thomas kept cattle, bullocks and of course horses. The cattle in Norfolk were predominantly Scottish and were brought in every year by drovers from Scotland. The quantity taken varied considerably depending on the estimated yields from the turnip crop. However, Thomas thought his own Norfolk breeds did as well as the Scottish so he seems to have had a mixture. He fattened about 40 bullocks a year on turnips, straw stubble and grass that grew between the stubble after cutting. Cattle would have been grazed on his marsh or common land and probably brought into the yard each night. It was a long, hard day for the labourers.

As pressure mounted to feed the growing population the agricultural revolution gathered pace. More and more marginal land was brought into production with the use of manuring, this transformed some of the land into the finest corn farms in England. Thomas used marle (claying, chalk and calcareous earth that acts as a fertiliser) on previously uncropped land as did other farmers in East Anglia. His came from Whittingham. A keel* (424 cwt) cost £5 5s and did two acres well according to Mr Francis which seems expensive but it brought more land into production and would last for about 30 years. Mr Francis had no natural clay of his own on his farm so he spread about 10 cart loads per acre as well as spreading it on fallow land for turnips.

* Keel was a unit used to measure coal in the northeast of England, being the quantity of coal carried by a keelboat on the Tyne and Wear rivers. In 1750 it was said to be equal to 8 Newcastle chaldrons (waggons), a measure of volume, or a weight of 21.2 long tons or 424 cwt (21.54 metric tons).

The use of cows, bullocks and horses produced yard dung which was also widely used as a fertiliser in every part of Norfolk. After foddering was over it was turned up in heaps in the yard or carted in heaps to the fields where it was turned over for mixing and left for some time before spreading and ploughing in. He carted it in heaps and the labourers would turn it. Thomas spread 12 loads per acre for turnips and eight for wheat. This large manuring was common in the district.

This then was the life of a yeoman farmer from Martham in around 1800 and one that appears to have been very successful, but sadly little remembered as this is the tomb at St Mary the Virgin where he and his wife, Elizabeth, now lay and it is somewhat overgrown.