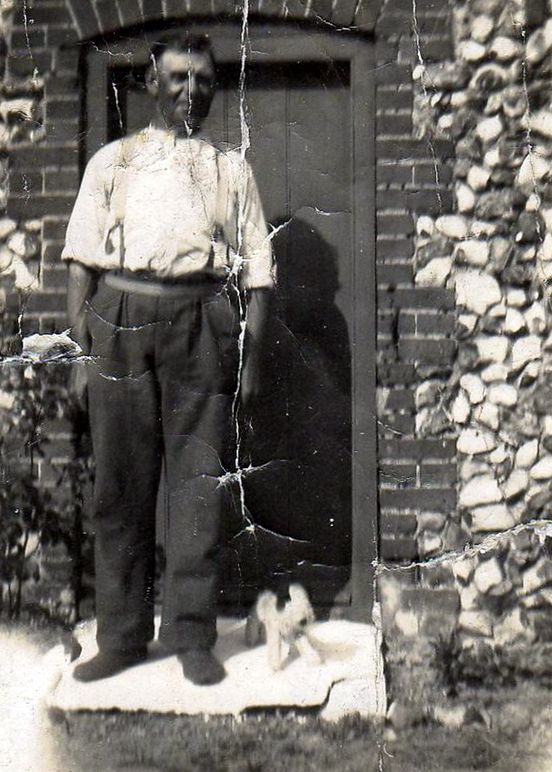

John Turner (1890-1965). War Hero of Martham

This is the story of John Turner who was an unlikely hero in a little-known naval clash in which armed British drifters fought Austrian cruisers. It illustrates the magnificent courage of a Martham fisherman turned man o’ war.

In an all-but forgotten clash between two ludicrously ill-matched naval armadas, in the 1st World War, off the coast of Italy John demonstrated remarkable bravery.

Compared to the titanic struggles taking place on the western front, the David and Goliath encounter between Austrian battleships and a force of British fishing boats in the Straits of Otranto was a small affair without a clear-cut victor and with relatively few casualties suffered by either side.

But such were the displays of defiance and individual acts of bravery that a potentially embarrassing setback for the Allies was somehow rendered heroic and an epic feat of arms.

The British press spoke of a desperate resistance which, in some instances, appeared to border on the suicidal, of drifters reduced to a line of floating ‘pepper pots’ confronting enemy cruisers with their puny guns and ordinary fishermen performing extraordinary deeds that all but beggared belief.

As it turned out the saga provided gallantry awash with improbable heroes and there were few actions to surpass the exploit of a humble seaman from Martham who was destined to be hailed as Norfolk’s own hero of the so-called Battle of the Otranto Barrage.

By all accounts, John Turner was an unprepossessing sort of man. Married with a family at the outbreak of the First World War, he was thought of as ‘a gentle giant’, a man who never shouted the odds but simply got on with his job as a fisherman on one of the countless herring drifters working out of Great Yarmouth.

Like thousands of others in his trade, he was moved by the call of duty to answer the Royal Navy’s appeal for volunteers to join the service’s burgeoning fleet of trawlers engaged in minesweeping and anti-submarine work from the warring waters of the Atlantic to the Adriatic.

Enlisting in the Royal Naval Reserve in February 1915, he underwent training at Milford Haven before, later that summer, sailing as a deckhand aboard the drifter Serene bound for a new theatre of war far-removed from the bleak fishing grounds of the North Sea.

He was part of a hastily assembled force of converted fishing boats requisitioned by the Admiralty from the east coast ports of England and Scotland, many of them manned by their original peacetime crews and despatched to the heel of Italy to help counter the threat posed by surface and submarine elements of the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

According to the commander of one of the drifter flotillas, they were ‘a magnificent lot’, though few, including no doubt John Turner, had the vaguest idea of naval etiquette. As the same naval officer observed: ‘The discipline was truly of a sort different from that in a battleship, but there existed a loyalty to their senior officers and a readiness for hard work which made me appreciate their values.’

That loyalty was never more seriously tested than during the early hours of May 15, 1917. On that misty Spring morning John found himself on board the drifter Garrigill. John had been promoted to Second Hand aboard the Garrigill, which had a larger crew than most because it had a 6-pounder gun and a wireless telegraphy.

The ‘Otranto Barrage’, as it was known, was established during the winter of 1915-16. By early 1917 it had grown to include 120 drifters, operating in rotation, supported by an assortment of motor launches, destroyers and larger vessels.

For the drifter crews, who had swapped fishing from ports like Yarmouth and Lowestoft it was a role that proved largely dull and monotonous. In a little over a year, the blockade, which one historian likened to a giant ‘sieve’, had accounted for just two submarines, one of which had fallen victim to depth charges dropped by Turner’s new boat the Garrigill.

That rare excitement had earned Garrigill’s skipper, Harold Goldspink, a Distinguished Service Cross, but the fight with a solitary submarine was as nothing compared with the onslaught unleashed by an Austrian raiding force spearheaded by three heavily armed light cruisers.

Under cover of a diversionary attack on an Italian convoy and taking full advantage of the early morning mist, the Saida, Novara and Helgoland passed unhindered through the ‘barrage’.

By the time the British commander of the drifter line realised what was happening it was already too late. The systematic destruction of the blockade was under way.

The fishermen reservists, operating in seven groups straddling the 45-mile strip of water separating Italy from Albania, scarcely knew what had hit them.

The first blow fell in the centre at around 3.15am when in the pre-dawn murk the cruiser set about the four drifters making up ‘C Division’ which included among its number John Turner’s drifter, the Garrigill.

Reports of the action that followed are sketchy, but what is clear is that the men of ‘C Division’ were determined to resist. Ignoring the Austrian captain’s calls to surrender, the four drifters immediately slipped their nets and scattered, their crews manning guns, which in the words of one skipper were fit only for the scrap heap, as they prepared to fight it out to the bitter end.

So far as one of the boats was concerned the end came quickly enough. The crew of the Quarry Knowe put up a brave fight but, with their wooden boat soon ablaze, they were forced to abandon ship.

Next in the line of fire was the Garrigill. As the only one of the four drifters with the means of sending a warning signal, it may have been seen as a threat to the operation. Either way, she found herself singled out for particular attention by the Saida.

But with shells bursting all around, Garrigill’s crew refused to give in. According to an official report, ‘all members of the crew behaved in a highly creditable manner’.

None more so than John Turner. While one deckhand answered the cruiser’s fire with shells from the boat’s six-pounder gun, the recently promoted acting second hand from Martham volunteered to perform what seemed a nigh-on suicidal feat of daring.

Realising that the enemy were bent on destroying the drifter’s wireless mast, Turner clambered ‘aloft’ under a hail of fire in a desperate attempt to ‘strike the topmast’.

To those looking on, it seemed as though every nerve-jangling second would be his last. His precarious progress drew a storm of fire during which shells could be seen ‘passing between the mast and the funnel’.

But somehow, against all the odds, his courage was rewarded and he succeeded in clearing away the damaged main mast before it was destroyed.

By some miracle that few could fathom, Turner and the Garrigill contrived to survive the Saida’s furious assault to limp back to base. Others among the drifter fleet, however, were less fortunate. All told, 14 boats were sunk and another four variously damaged during an attack lasting little more than two hours. The losses included Turner’s original boat, the Serene. All bar one of her crew were among more than 70 men taken prisoner.

The exception was Joe Hendry who, refusing calls to surrender, remained on board till the boat sank beneath him and was eventually picked up from the water by another drifter some hours later.

Such instances of heroic resistance were not unique. Despite the unjust criticism levelled by senior officers at those drifter crews who had capitulated without a fight, thus failing in the words of the Admiralty to uphold ‘the traditions of the Navy by… fighting to the last’, there were numerous instances of outstanding courage in the face of ‘overwhelming odds’.

They were headed by the Scottish skipper of the Gowanlea. Rather than surrender, Joe Watt had urged his crew to give ‘three cheers for a fight to the finish’ before steaming straight towards one of the cruisers, an act of crazy defiance which he incredibly survived to receive a Victoria Cross.

All 11 crew members of the gallant Garrigill were recommended for the nation’s second highest award for bravery, the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, but in the end a parsimonious Admiralty granted just one – to the heroic mast-climber John Turner. His was one of just four such awards from an original list of 45 submitted by the Admiral commanding the British Forces in the Adriatic.

The distinction proved a rare highlight in an otherwise unremarkable war. Following further service in home ports, John Turner returned to England early in 1918 and served at Milford Haven, Grimsby and on the Clyde until March 1919, when he returned to Martham. He spent the rest of his life in Martham, living in Stone Cottages, Cess, working variously as a fisherman, boatbuilder and marshman his focus was not on past glory but on providing for his growing family.

He and his wife Susanna had four children. One of his grandsons, Melvin Grimble, and a granddaughter, Pauline Parker, still live in Martham.

John died in 1965, aged 74, at Northgate Hospital, Great Yarmouth.

With thanks to Steve Snelling of the Easter Daily Press for most of the information in this article.